Fat Tuesday means gumbo

I recently lost my wife (and Illinois Times food columnist), Julianne Glatz. When one loses his best friend of 45 years, the mother of his children, the Nana of his grandchildren, a tremendous void suddenly appears. I can’t bring her back, but I can’t let go either.

Her 10 years of writing weekly columns for Illinois Times resulted in many 10 p.m. dinner times, and afternoons and evenings of tiptoeing around her, trying not to disturb her flow of consciousness while she was working on her columns. There were many late nights when I was starving, but had to round up lights and set a table to photograph my dinner for her column before I could eat it.

We hosted her memorial reception in our home. The receiving line stretched far outside and wound, fittingly, through her kitchen. Now that the guests are gone, the big old house she loved so much stands quiet. The kitchen is spotless and the only aromas are coming from her memorial flowers.

After finishing my first day back at work since her passing, I procrastinated going home. I met a friend at the nearby Curve Inn for a beer, hoping for a brief respite from my grieving. I hadn’t realized it was Fat Tuesday. The tavern was offering complimentary gumbo. Oh how she loved making gumbo!

Julianne’s gumbo started with a roux.

“Don’t get too close!” she warned. “They call this stuff Cajun napalm because if it splashes on you, it sticks to your skin and burns badly.” She would cautiously whisk flour into a heavy black skillet of smoking oil. As she stirred the mixture, it slowly turned pale tan, then a medium brown nutmeg color, gradually darkening to a mahogany red brown. The trick was to

stir the oil and flour combination at just the right temperature until

it barely begins to turn black, moments short of burning. If black

specks started to form, you’ve gone too far and have to throw it out and

start over. If you stop short, at the dark red brown stage, you’ll

still have a tasty gumbo, but it won’t be as memorable as a gumbo made

with a perfect dark roux. It is a risky procedure, but if all goes well

the reward is an unforgettable eating experience.

It

took Julianne two days to make gumbo. The first day she prepared the

chicken stock, putting four chickens into her five-gallon stockpot with

carrots, onions, garlic, celery, peppercorns, thyme, cloves and bay

leaves. She would simmer the stock an hour, skimming off the scum that

had risen to the top. The chickens were removed from the pot, cooled,

then skinned and boned. The meat was reserved in the refrigerator, and

the skin and bones were returned to the stockpot to simmer all night

over low heat.

The

next morning, the stock was cooled so the fat could rise to the top and

be removed. While the stock cooled, Julianne would peel four pounds of

shrimp. She added the peels to the defatted stock, which was simmered

another four hours and strained. Meanwhile, she would halve the shrimp

and dice the chicken. She’d then cut up 4 pounds of Andouille sausage, 8

cups of onions, 6 cups of bell peppers, and 4 cups of celery. She’d

mince a ½ cup of garlic and measure out a bewildering array of herbs and

spices.

The making of

gumbo is work in the sense that camping is work. The fulfillment comes

as much from the process as the outcome. It is a creative act with a

degree of unpredictability. All five senses are pleasurably stimulated.

It can appeal to our spirit of adventure. It links us with our primitive

roots. But it’s not easy. The easy way is touted in magazines and TV:

easy recipes, easy ways to entertain, to rear children, to establish and

maintain loving relationships. How often, in our quest for ease, our

pursuit of predictability, our avoidance of effort, do we sacrifice the

opportunity to experience the remarkable, the extraordinary – especially

when they are the results of our own efforts and creativity? “Just open

the package. Pour in a cup. Add boiling water. And stir it up.” Easy.

Predictable. But consummately boring.

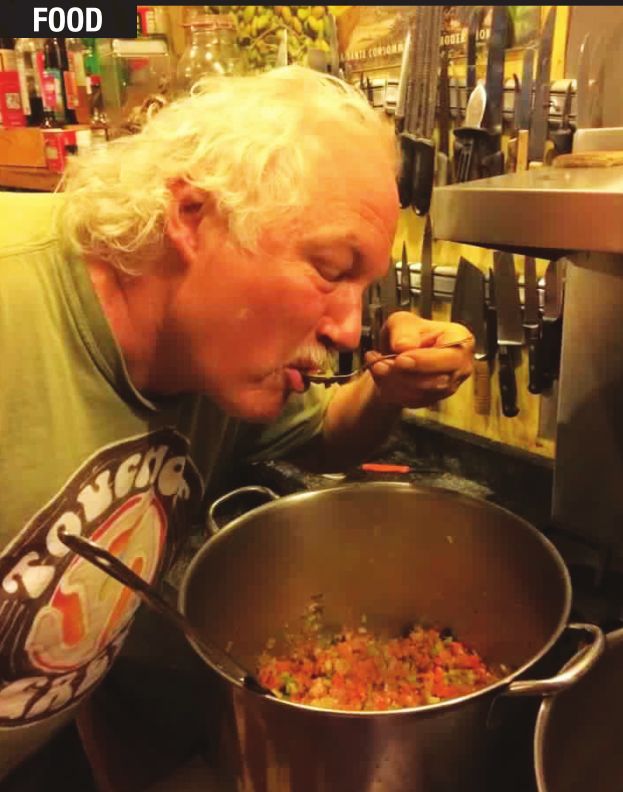

As

Julianne’s roux approached it’s climactic precipice, she would stir in

the diced vegetables for a quick cool-down. The roux would be added to

the stock. Then the sausage, the chicken and finally the shrimp. At last

the dark, earthy aromatic mixture was ladled over a mound of rice in a

shallow soup bowl. My responsible, predictable self would blow on the

spoon and try to delay gratification. My creative, adventurous self

would take over and I would inevitably end up burning my mouth.

Her

gumbo was always fantastic. Earthy, mysterious and complex, with layers

of flavor that compel you to take another spoonful, then another, and

still another to try to experience them all.

Julianne’s

gumbo also tasted great the next morning, right out of the

refrigerator. The coolness always felt good on my burned palate.

For Julianne’s recipe, “Dark roux gumbo with shrimp, andouille and chicken,” go to illinoistimes.com.

Peter Glatz is the husband of Julianne Glatz, IT’s food

writer who died Feb. 4. Peter, an enthusiastic amateur cook, was

Julianne’s dishwasher for 42 years. A dentist in private practice, he is

also harmonica player for the Last Chance Blues Band.