Criminal justice reform promises to remedy Illinois’ racial disparity

In 2013, one out of every 266 people in Illinois was in prison. For African-American residents, it was one in every 68 people.

That’s just one of the shocking facts illustrating the serious racial disparity in Illinois’ criminal justice system. About 60 percent of the state’s prison population is black, despite African-American people making up only about 15 percent of the general population. At about 28,200 inmates, there are nearly twice as many black inmates in Illinois prisons as there are white inmates.

From their first contact with police to the minute they finish parole, people of color in the criminal justice system face more challenges – and often subtly different ones – than white people in the same system. The result is that people of color have dramatically higher odds of being sent to prison and being branded with a scarlet letter in the form of a criminal conviction, which can haunt them the rest of their lives.

However, a band of criminal justice experts in Illinois is working to reduce the state’s prison population, and that work has led them to examine solutions for this racial disparity.

The fixes they’re considering aren’t official yet, and implementing some of those ideas will undoubtedly prompt battles in the Illinois Statehouse. Still, the state is drawing ever closer to smart solutions that could drastically change life for people of color in Illinois.

A festering problem

This state has long struggled with overcrowded prisons. During the 1970s and 1980s, directors of the Illinois Department of Corrections warned of “serious consequences” from overcrowding, ranging from poor rehabilitation to outright violence. From 1988 to 1994 – the heyday of “tough on crime” sentencing policies – the state’s prison population rose by more than 73 percent.

In total, Illinois’ 25 adult prisons were designed to hold 31,000 inmates. As of Jan. 1, however, there were more than 45,000 inmates in custody. Rather than refer to the prisons’ collective “design capacity,” the Illinois Department of Corrections often talks in terms of the “operational capacity” of its prisons, a euphemism that represents IDOC’s efforts to make do in an untenable situation. Often, that means putting two inmates in a cell designed for one, a practice known as “double bunking” which contributes to tension and violence among inmates.

The response to overcrowding in past decades was simply to build new prisons. From 1980 to 2004, Illinois built 21 prisons designed to hold more than 20,300 inmates. However, the state’s dire financial situation means building more prisons is no longer a viable option.

For fiscal year 2015, which ended in June 2015, Illinois’ corrections spending totaled almost $1.4 billion. With Illinois facing more than $8 billion in unpaid bills and a huge unfunded pension liability, that $1.4 billion for corrections becomes a cost ripe for slashing to relieve budgetary pressure elsewhere.

A year ago, in February 2015, Gov. Bruce Rauner created the Illinois State Commission on Criminal Justice and Sentencing Reform through an executive order. Tasked with decreasing the state’s prison population 25 percent by 2025, the 28-member commission is composed of state lawmakers, current and former prosecutors and defense attorneys, judges, law enforcement, criminal justice researchers, and providers of drug treatment and prison rehabilitation programs – essentially the main people who make the justice system work the way it does.

At a Jan. 14 commission meeting, Rauner said his visits to Illinois prisons reinforced his belief that criminal justice reform is essential for the health of the state.

“It was a very emotional, very overwhelming experience,” he said. “It’s emotionally stunning. These are harsh, depressing, hostile environments.”

Although several past governors have created blue ribbon panels to examine the prison problem and suggest solutions, little has changed – at least not for the better. The current commission, however, may be different. The waning influence of “tough on crime” politics, the growing call for reform on both the right and the left, and the state’s budget crisis coming to a head all signal unprecedented political will in the Illinois Statehouse to implement solutions.

Rauner said in no uncertain terms that he would work to get the commission’s recommendations adopted.

“I can guarantee you that I will work tirelessly to make sure this isn’t something that just gathers dust,” he said.

Disparity and despair

Of

the 48,921 inmates in Illinois prisons on June 30, 2014, IDOC’s 2014

annual report shows 28,333 were black. That’s just under 58 percent,

despite the fact that African-Americans made up only 14 percent of the

state’s overall population that year.

Roughly

one out of every 264 people in Illinois were in state prisons the day

that count was taken, but for the state’s black population, that ratio

was more than four times higher: one out of every 64. That’s actually a

slight improvement over 2013, when the ratio was one in 68.

This problem isn’t unique to Illinois.

According

to The Sentencing Project, a national reform advocacy group, state and

federal prison statistics show one in 17 white men will be imprisoned at

some point. Compare that with one in three black men and one in six

Latino men. The numbers for women are no less skewed: one in 111 white

women will be imprisoned at some point, versus one in 18 black women and

one in 45 Latina women.

The

causes of this disparity are a combination of systemic racism and

poverty. Defined simply, systemic racism is the misuse of power –

whether intentional or not – based on race. Driven by prejudicial

attitudes and discriminatory rules or laws, systemic racism affects

housing, banking, marketing, media, employment, law enforcement and any

other institution created or controlled by white people. It’s often

unintentional – the byproduct of unexamined processes and privileges

that benefit white people to the detriment of minorities.

In

the context of the criminal justice system, systemic racism manifests

as disproportionate minority contact with police, higher arrest rates,

more severe criminal charges, higher conviction rates, longer sentences

and uneven enforcement of parole provisions.

The

most infamous example is the former federal sentencing guideline that

treated one gram of crack cocaine – which saw heavy use in impoverished

black communities during the 1980s and 1990s – as equal to 100 grams of

powdered cocaine, used more prevalently by white defendants. The result

was that black defendants in crack possession cases wound up with

sentences several times longer than white defendants caught with similar

amounts of a closely related drug. The federal Fair Sentencing Act of

2010 revised that 1-to-100 ratio to 1-to- 18, but the law was not made

retroactive, so many black inmates stayed in prison even after the

discriminatory sentencing guideline was revised.

In 2013, a federal appellate court in Tennessee wrote a decision applying the law retroactively.

“The

discriminatory nature of the old sentencing regime is so obvious that

it cannot seriously be argued that race does not play a role in the

failure to retroactively apply the Fair Sentencing Act,” the court wrote

in its decision. “Like slavery and Jim Crow laws, the intentional

maintenance of discriminatory sentences is a denial of equal

protection.”

That

decision was later overruled on rehearing, and the U.S. Supreme Court

declined to take the case in 2014. That means inmates given

disproportionate prison time before the Fair Sentencing Act could not

have their sentences reduced under that law.

Justice under the microscope

Making

changes to an institution as vast and complex as the criminal justice

system means closely examining how the system operates and why it’s set

up that way. On Jan. 14, Rauner’s Commission on Criminal Justice and

Sentencing Reform released a list of proposals under consideration which

would focus on the severity of drug sentences, disproportionate

minority contact with law enforcement and other changes.

One

of the main areas under examination is drug offenses. Of the 48,921

inmates counted in IDOC’s 2014 annual report, 8,565 were serving time

for convictions under the state’s Controlled Substances Act, while

another 672 were in for marijuana offenses. Combined, those two offense

categories account for 9,237 inmates, which means drug offenders account

for almost 19 percent of the state’s prison population. That includes

both violent and nonviolent offenders, addicts and dealers.

Megan

Alderden, associate director of research and analysis for the Illinois

Criminal Justice Information Authority, told the reform commission on

Jan. 14

that African-Americans account for more than 52 percent of nonmarijuana

drug arrests and more than 62 percent of new inmates incarcerated for

nonmarijuana drug convictions.

Discussion

at the meeting made clear that few experts have faith in the

decades-long “war on drugs,” which has seen drug abuse nationwide

treated as a crime rather than a sickness. Rauner told the commission he

wants to see more rehabilitation services for inmates with drug

problems and mental health issues, along with better counseling and job

training programs.

Additionally,

the commission is considering revisions to the state’s automatic

“enhancements” that elevate crimes to more severe classifications for

sentencing. One example is the current state law mandating that a

defendant’s third or subsequent Class 2 drug felony automatically

becomes a Class X felony, raising the possible sentence range from 3-7

years to 6-30 years.

David

Olson is a member of the reform commission and a professor of criminal

justice and criminology at Loyola University in Chicago. He analyzed

prison data and found that most inmates receive sentences on the low end

of the sentencing guidelines, which he says shows that judges typically

don’t apply the harshest sentence possible. Illinois has different

levels of severity for felonies, but the levels have overlapping

guidelines for sentencing. Olson says most inmates sentenced at the low

end of the possible range could have been sentenced to the same amount

of prison time under a less severe felony class.

An

inmate sentenced to seven years in prison for a Class 2 felony may be

eligible for early release, while an inmate given the same sentence for a

Class X felony may not be.

Olson

also points to a state law which makes possessing or dealing 15 or more

grams of cocaine or heroin a Class 1 felony, the second most severe

felony class, carrying a sentence from 4 to 15 years. (Olson says a gram

is roughly equal to one sugar packet.) Instead, Olson suggests creating

a graduated penalty system based on the volume of drugs involved and

whether the defendant is charged with dealing drugs or mere possession.

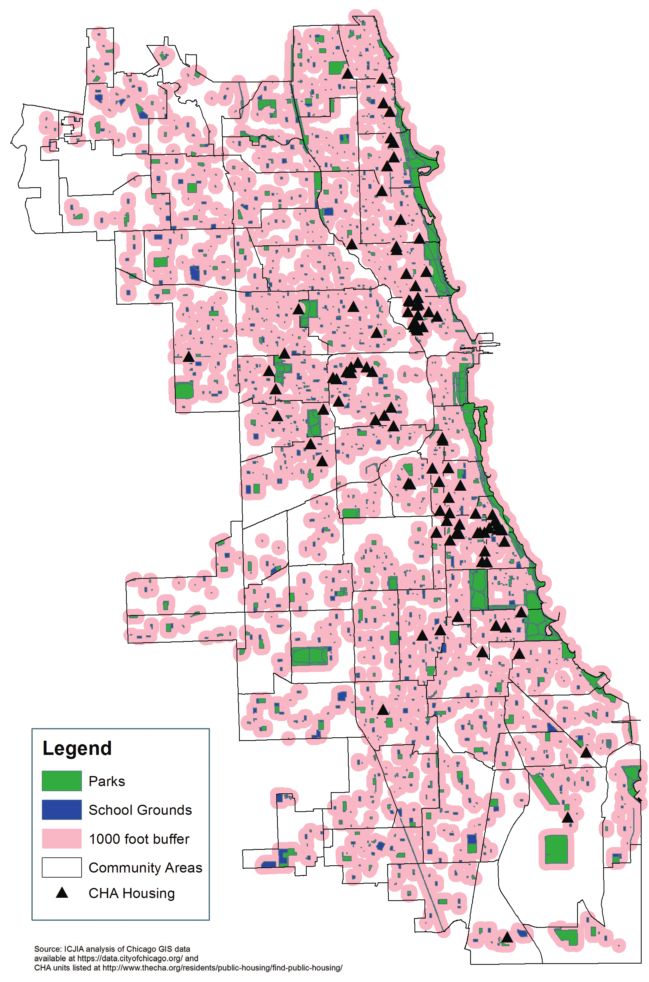

Another

section of Illinois law automatically elevates the felony class for

possession and dealing drugs when it takes place within 1,000 feet of a

church, school, park or other designated location.

Alderden

showed the commission a map of Chicago, where the vast majority of the

state’s inmates come from. The map depicted as many schools, parks and

public housing areas as Alderden could plot, along with a 1,000-foot

radius around each one. The result covered nearly the entire map,

showing that it’s nearly impossible to commit a drug offense in Chicago

without triggering the automatic sentence enhancement.

While the 1,000-foot rule is wellintentioned, Olson says, it’s sometimes an overreaction to the “crime du jour.”

“One of the easiest ways to express concern is to up the penalties,” he said.

For

example, Olson questions the logic behind elevating the penalty against

a defendant charged with selling drugs near a school even if the school

is out of session. Instead, he proposes making the rule optional, so

that courts have discretion based on the facts of each case.

Minority

communities often have more contact with the criminal justice system,

so the commission is considering changes aimed at making the system more

fair and responsive.

Springfield

attorney Rodger Heaton, chairman of the commission, previously worked

as a federal prosecutor, criminal defense attorney and professor at the

University of Illinois College of Law. He says the commission is

intentionally addressing the causes and effects of racial and ethnic

disparity in the justice system.

Among

the proposals is requiring training on race and ethnicity for police,

prosecutors, public defenders and judges, as well as better data

collection by courts, police departments and probation offices.

Alderden

says Illinois lacks data to make informed decisions on race and

ethnicity. She says the state has “consistent, reliable and complete

data” from only two points in the system: at arrest and at admission to

IDOC.

“That’s an

important lack of information,” she said. “If we don’t measure how or

the different ways people flow in and out of the system, we don’t really

understand the impact of our policies and practices.”

Currently,

most police departments in Illinois don’t participate in the National

Incident-Based Reporting System, which collects detailed information

about crimes, arrests and demographics of offenders and victims.

Likewise, some courts don’t submit data to the Criminal

History Record Information system, which collects information on

criminal cases, including charges filed, convictions and sentencing. The

reform commission may suggest legislation requiring police departments

and courts to submit that information, along with requiring probation

offices to collect data on parole revocations.

The

commission is also examining better training for police dealing with

mentally ill people, reducing penalties for “look-alike” substances, and

reducing penalties for burglary and theft in certain situations, such

as theft from an unoccupied vehicle.

The

proposals and a handful of others are still unofficial, but discussion

among the commissioners indicated strong agreement on the need for such

changes. The commission was due to issue its final report at the end of

2015, but the group continues to work, with meetings scheduled into

early March. The end of the spring legislative session is scheduled for

May 31, so it’s possible the commission’s final recommendations will be

in bill form by then. Rauner says he’ll implement whatever proposals

don’t require legislative action. Taken together, the current proposals

represent a smarter justice system and a potential leap forward for

communities of color plagued by mass incarceration.

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].