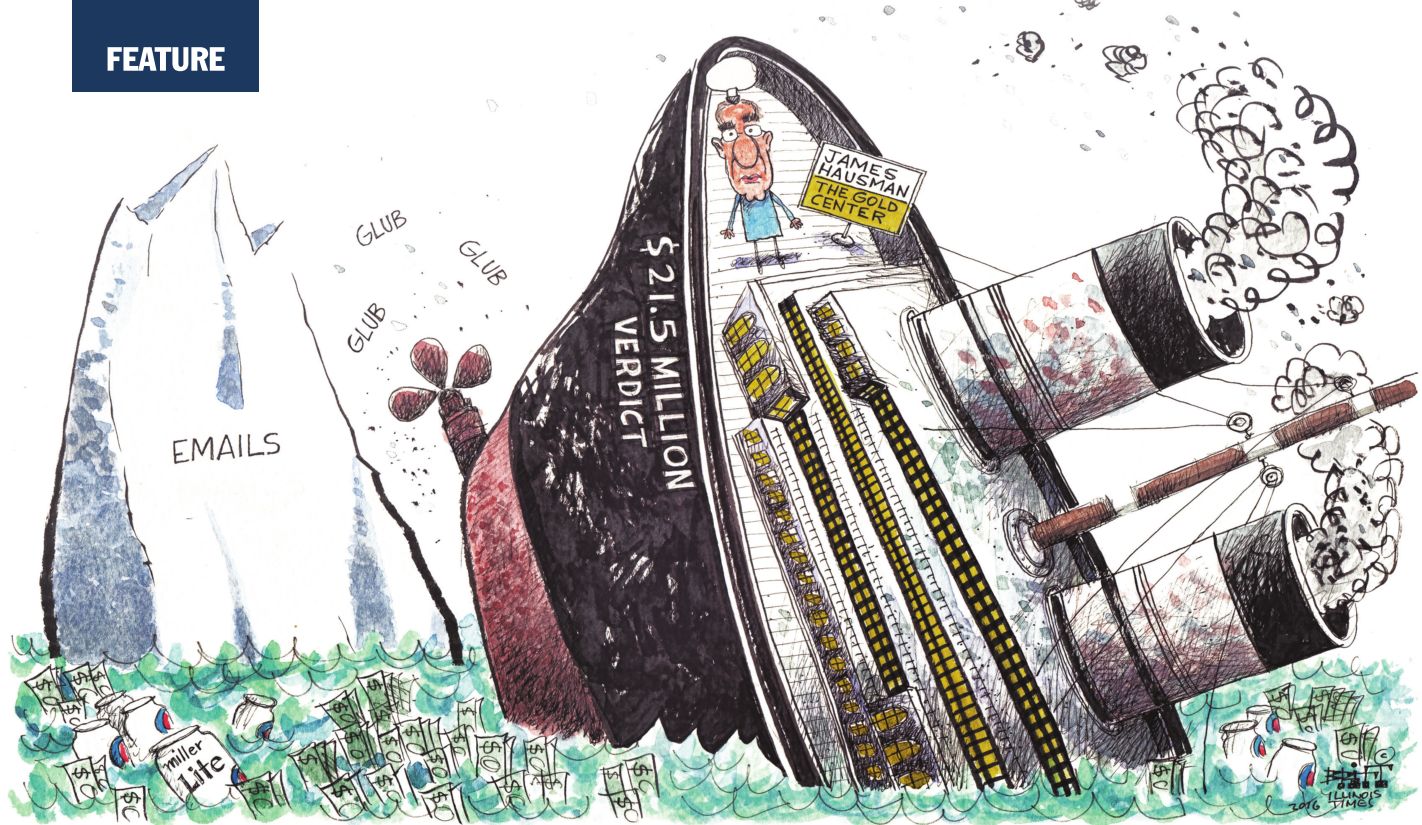

Scorned woman scuttles $21.5 million cruise-ship verdict

Amy Mizeur didn’t hold back on her way out the door when she was terminated from her job at The Gold Center in Springfield last spring.

“This is what you get when you refuse to screw your boss,” Mizeur yelled over her shoulder, according to a Gold Center manager tasked with telling the Springfield woman that her services were no longer required.

The matter did not end there. Mizeur has prompted a stunning reversal in a federal lawsuit against Holland America, a Seattle-based cruise ship line, filed by James Hausman, former president of The Gold Center. Hausman sued after he was struck in the head by a sliding glass door aboard a Holland America ship in 2011. Hausman claimed that he suffered a brain injury so serious that he suffered seizures, dizziness and vertigo. His life, Hausman says, has never been the same.

A Seattle jury in October awarded Hausman $21.5 million. But Hausman may not collect a nickel, thanks to Mizeur. Eleven days after the verdict came in, Hausman’s former personal assistant contacted a Holland America lawyer, saying that her ex-boss had faked injuries and hidden evidence from the cruise line.

Mizeur had emails and at least one photograph to back her assertions that Hausman had hoodwinked the court. Based on information from Mizeur and proof that Hausman had not turned over emails to Holland America prior to trial, U.S. District Court Judge Barbara Jacobs Rothstein on Jan. 5 threw out the $21.5 million verdict and ordered a new trial.

Attorneys for Hausman dismiss Mizeur as an angry ex-employee and would-be extortionist who cannot not be trusted. While Mizeur’s testimony and emails convinced the judge to order a new trial, convincing a jury that Hausman doesn’t deserve a verdict in his favor is another matter, says Richard Friedman, attorney for Hausman.

“If they want to make Ms. Mizeur their star witness (at a second trial), the verdict may be larger,” Friedman says.

From house cleaner to personal assistant Mizeur’s has not been a smooth life, judging by files in Sangamon County Circuit Court. She was a house cleaner earning $17,000 a year when she filed for divorce in 2006. She had troubles with drugs, prompting the judge in her divorce case to order drug tests. She skipped tests on several occasions, tested positive for cocaine at least once and temporarily lost custody of her son as a result. More recently, she has been the victim of domestic violence at the hands of a boyfriend, court records show. She was arrested last August on suspicion of domestic battery, but has not been charged with a crime.

Mizeur initially worked as a cleaner when she was hired at The Gold Center, where she earned $15.38 per hour. One month after she was hired in 2013, Hausman promoted her to become his personal assistant and driver, according to court records. She says that she worked as many as 12 hours a day and was often called in on weekends; Hausman says that she worked between 30 and 40 hours a week. In any case, Hausman thought enough of her that his employment contract with The Gold Center, which he sold to local car dealer Todd Green in 2014, required that Mizeur be employed as his assistant.

“My desk and computer were in his personal office at The Gold Center,” Mizeur writes in a court affidavit. “No other employees were stationed in his office.”

Hausman gave Mizeur a credit card that bore both his name and hers – Kathy Kincaid, a vice president at Carrolton Bank that issued the card, says in a court affidavit that Mizeur had such a spotty credit history that she could not get a card on her own. Mizeur says that she used the card to pay personal expenses and that Hausman picked up the tab. She says that he also gave her cash, as much as $5,000 at a time, slipped directly into her purse.

“He

told me he did not want the others at The Gold Center to know that he

was giving me this money,” Mizeur says in an affidavit.

Mizeur

says that she traveled with Hausman to his second home in Wisconsin as

many as a dozen times; Hausman, however, puts the number of Wisconsin

trips at four in federal court documents. During a December court

hearing, Mizeur testified that Hausman vowed to provide her with

financial support in the event of his death.

In court, Hausman, 61, denied any romantic interest in Mizeur, 37, but emails suggest otherwise.

“I

slept in your bed upstairs last night to smell you,” Hausman wrote in a

Jan. 6, 2014, email to Mizeur. “That’s how bad it is on me.”

Hausman shared things with Mizeur that he kept from his wife.

“Carol

(Hausman’s wife) does not even know that I went to see the doctor twice

a few weeks ago, or the results,” he wrote in a Jan. 10, 2014, email.

“You are the only one that knows what is going on.”

Friedman

acknowledges that it is impossible to reconcile Hausman’s statements in

emails with his courtroom denial that he ever had a romantic interest

in Mizeur.

“I think

he’s embarrassed,” the lawyer says. “Now, in the present day, I think

he’s got disbelief that he did have a romantic interest in her. He is,

clearly, flirting with her (in emails). Both of them are consistent in

saying nothing physical ever happened.”

It didn’t take long for friction to develop between Mizeur and Carol Hausman.

“It

seems like u don’t want me to work after 530 which if we weren’t

actually doing work I would understand but I am simply trying to do the

best that I can,” Mizeur wrote in an email to Hausman’s wife less than

three months after she became Hausman’s assistant. “The things u said to

me last week have been eating at me u told me I was not qualified to

assume the role as his assistant that truly hurt me. That makes me feel

that your opinion of me is I’m nothing more than a house cleaner.”

By

early 2014, Hausman’s relationship with his wife was deteriorating. In

February of that year, he moved to a hotel while Mizeur worried that she

would get the blame.

“I

do not want the gossip in town ... that u 2 split bc of me,” Mizeur

wrote in a Feb. 23, 2014, email. “I’m very fearful of that.”

After

two weeks in local hotels, Hausman returned home. Five months later,

Hausman transferred Mizeur out of his office to the front counter at The

Gold Center, and he told Josh Wagoner, a Gold Center manager, to change

whatever contract might exist that required her to work for him. He

wrote that he did not want Mizeur fired.

“I want her to succeed,” Hausman wrote in an email to Wagoner.

Hausman also informed Mizeur that her life at work would change.

“I

would suggest to you that actions here at the office, that you have

become used to, should stop immediately, such as texting, personal phone

calls, being late, or leaving early when not scheduled, and Internet

surfing,” Hausman wrote in an email to Mizeur. “You will have a new set

of rules that I will not control.”

Mizeur accused Hausman of punishing her because she had refused to sleep with him.

“You

clearly believe I can be paid off for sex or companionship,” Mizeur

wrote in an email to Hausman one week after she was moved out of his

office. “That is what you call a whore. I am not that and never will be.

When I don’t do what you have

asked or suggested you take things away and make me suffer. I asked to

borrow $10,000, which is NOTHING in comparison to what you have just

handed to the rest of the employees but because it is me and I won’t

sleep with you I get nothing.

“I

have done everything you have EVER asked of me except give you the

sexual and emotional advances you have asked for. I believe there is a

word for that. It’s called blackmail. I’m a lot smarter than you give me

credit for.”

Pay me

or else Mizeur’s banishment from Hausman’s office didn’t last, according

to a court affidavit from Wagoner, who says that she soon “floated

back” to her prior duties, working both inside and outside Hausman’s

office and frequently calling him. Less than a week after telling Mizeur

that she was no longer his assistant, Hausman bought her a gun as a

birthday gift.

During

her time at The Gold Center, Mizeur had Hausman’s “full satisfaction and

support,” Wagoner declares in his affidavit. Wagoner says that Hausman

told him that Mizeur was “at the highest level of trustworthiness, and

as such was privy to all his personal information, had free access to

his office throughout the time she was employed, and was privy to all

company matters between management and the shareholders.”

Hausman’s

support ended on April 4 of last year, when he accused Mizeur of

forging a $2,000 check and asked that she be fired. Mizeur insists that

she signed Hausman’s name to the check with his knowledge – she says

that she called him after overdrawing her checking account and he

authorized her to write the check.

Wagoner, not Hausman, told Mizeur that she was fired. She did not react well.

“You

just fired me for not sleeping with you again,” Mizeur wrote in an

email to Hausman. “That is pathetic!!!! You took everything from my son

because I wouldn’t FUCK YOU! I hope Holland America reads ALL my emails.

… You make this right or you (sic) life is going down with mine.”

At

least three times, Mizeur in the days after her termination threatened

to help Holland America Line defeat Hausman in court. And she demanded

money.

“Since you have

ruined my family and my life I am willing to do the same to you and

yours,” Mizeur wrote in an email to Hausman six days after she was

fired. “I have no money, no job, no insurance, no way to take care of my

son all because of you not getting your assistant to fuck you so you

could hand out cash. I can start forwarding my emails and telephone

records to…HAL. … I asked for you to pay me off like you have the rest

of the people you have fucked over in this world. You aren’t willing to

do that? Then I will make sure everyone including your wife and child

know everything I know about you. And that is not going to be pretty.”

In that same email, Mizeur writes that Hausman’s romantic interest in her was obvious.

“Everyone

has seen you stalk me,” Mizeur writes. “You are a sick man. Now I will

go away as soon as you pay for sexually harassing me for over a year.”

Some

of the emails produced by Mizeur after the trial suggest that she took

Hausman’s health complaints seriously. For example, Mizeur contacted a

Wisconsin clinic to ask if Hausman could participate in a study aimed at

helping people with brain injuries. Mizeur sounds sincere in emails to

Hausman’s wife as she describes her boss’s troubles with memory and

seizures.

“The seizure

last night lasted 5-10 minutes at the most,” Mizeur writes in a 2014

email to Hausman’s wife. “He got the blank look on his face, eyes

started to water and pointed to the drawer where the pills are and

opened his mouth. … It was not a very bad one other than the few minutes

he began to pound on the table.”

Hausman

in emails to Mizeur described his troubles with seizures, and Mizeur

gave her boss advice on how to tell his daughter about seizures.

“Tell

her what a seizure is and that it can be scary but doesn’t have to be,”

Mizeur suggests in a 2014 email to her boss. “Explain to her u don’t

want her to be afraid and encourage her to ask lots of questions any

time she’s feeling like she doesn’t’ understand and gets scared. Talk to

her.”

Such emails undermine Mizeur’s assertions and help his client’s case, Friedman says.

“Some

of the documents that have now come out help support Mr. Hausman’s case

and cast doubt on Ms. Mizeur’s story,” the lawyer says.

Mizeur

now says that Hausman had no trouble performing tasks that he claimed

in his lawsuit were difficult or impossible. While at work, she says, he

acted as if he was having mental and physical problems but those

problems disappeared when he left the office to have lunch, drinks or

dinner with her. She says that he watched videos of people suffering

seizures on the Internet and told her that he wanted to see what

seizures looked like.

Mizeur

says Hausman drank a case of beer each day and was concerned that

Holland America would claim that memory problems and other maladies were

caused by drinking, not a head injury. Prior to trial, Holland America

was curious about Hausman’s drinking habits and requested emails

containing the word “beer.” Hausman didn’t deny a fondness for Miller

Lite.

“Meetings in my

office with people…I might have six or eight beers,” Hausman said during

a pretrial deposition when asked how much he drank prior to the cruise.

“Sometimes…some people might come over at 5:30 at the office, or 5

o’clock. And we might stay there until midnight. And you know, 12, 14

beers in a night. You know, something like that.”

Witnesses at the trial testified that they had never seen Hausman intoxicated, although they often saw him with beer.

“He

was often walking around with his Miller Lite can in his hand and

joking that he had a second one in his pocket,” testified a fellow ship

passenger.

After the

trial, Mizeur gave Holland America a photograph of Hausman standing next

to his Lincoln Navigator loaded with shelving. At Hausman’s request,

Mizeur says that she took the photograph outside Hausman’s Wisconsin

home after Gold Center employees had warned that the shelving would fall

from the Navigator’s roof during the drive from Springfield. Mizeur

says that Hausman unloaded the shelving, which required him to balance

on the vehicle’s frame and seats while removing shelves from the roof.

Contrary to Hausman’s claims, Mizeur says that he was able to drive long

distances without difficulty.

Friedman

points out that his client, against his physician’s advice, has never

denied driving long distances. He also says that Hausman never said that

he couldn’t unload shelving from a vehicle.

“It’s

kind of like the defense is taking the position that if he can do

anything, he’s not brain damaged,” Friedman says. “The fact is, he can

do stuff. He’s trying to stay as active as he can.”

In

her Jan. 5 decision nullifying the jury verdict, Judge Rothstein

focused on emails, both contents and Hausman’s failure to turn over

emails to Holland America prior to trial. Emails produced by Mizeur, the

judge found, exposed “grave inconsistencies” in Hausman’s trial

testimony.

“You don’t

know this, but yesterday, I spent most of the day on a 10-foot later

(sic), with a fire axe chopping off the ice that had accumulated over

the front porch of the house, followed by the garage hose, on hot water

to melt of (sic) the ice, followed by a couple of avalanches of snow and

ice off of the roof, followed by me scooping the snow and ice of (sic)

of the walk way,” Hausman wrote in a 2014 email that Mizeur produced

after the trial. “Some of the ice was 15 inches thick, very heavy to

pick up or scoop.”

Hausman painted a different picture for the jury, testifying that he couldn’t even change a light bulb.

“Why can’t you change a light bulb?” Hausman’s lawyer asked.

“The

vertigo, getting up on a ladder…I’m not supposed to get on a ladder,”

answered Hausman, who said that he feared he would fall and hurt himself

if he used a ladder to change a light bulb.

Mizeur

gave more than 60 emails to Holland America’s lawyers, including dozens

from a Yahoo email account that Hausman had not previously acknowledged

even existed. Mizeur said that Hausman, in a panic over Holland

America’s demand for emails, spent days deleting emails from a Hotmail

account and also insisted that she delete emails from her computer and

phone.

Hausman claimed

that he had forgotten about the Yahoo account, but the judge, who

focused on emails that should have been turned over to Holland America,

didn’t buy it. She also didn’t believe Hausman’s explanation that he

routinely deleted messages from his Hotmail account and wasn’t trying to

hide anything.

“Mr.

Hausman retains his emails, except when the emails have the potential to

harm him, in which case, he destroys them,” Rothstein wrote in her Jan.

5 decision.

Rothstein

didn’t believe Hausman when he said that Mizeur forged a check.

Hausman, the judge determined, had routinely given Mizeur money, and she

found it telling that Hausman didn’t contact police about the alleged

forgery. Beyond emails and checks, Rothstein focused on demeanors when

Hausman and Mizeur testified before her during a December hearing.

“Ms.

Mizeur answered each question put to her in a straightforward and

complete manner,” the judge wrote in her Jan. 5 decision. “When

confronted with the emails in which she threatened to ruin Mr. Hausman’s

life unless he ‘paid her off,’ she admitted that she wrote them but

explained that it was done out of shock and anger at being falsely

accused of a crime and fired as a result. … (T)his court finds Ms.

Mizeur to be a truthful witness.”

The judge found Hausman “evasive and untrustworthy.”

“He

was confused or claimed memory loss when confronted with a question or

exhibit that appeared to undermine his claims, yet was animated and full

of information when his testimony supported his case,” the judge wrote

in her Jan. 5 decision. “(T)he court concludes that Ms. Mizeur is a

credible witness and Mr. Hausman is not.”

And, just like that, $21.5 million disappeared.

“Based

on the evidence…this trial judge concludes that a miscarriage of

justice occurred in this case,” Rothstein wrote in her decision

nullifying the verdict.