Expressing our unconscious unease about immigrants

The dread of the invader runs deep in every human. The savage acts on it unthinkingly, by reaching for a club; the civilized man and woman is no less vulnerable to it but considers it disreputable, rooted as it is in ignorance and racism, and tries to calm it with reason. The fear remains nonetheless, and if we suppress its expression in one context it will push its way into our thinking in other contexts.

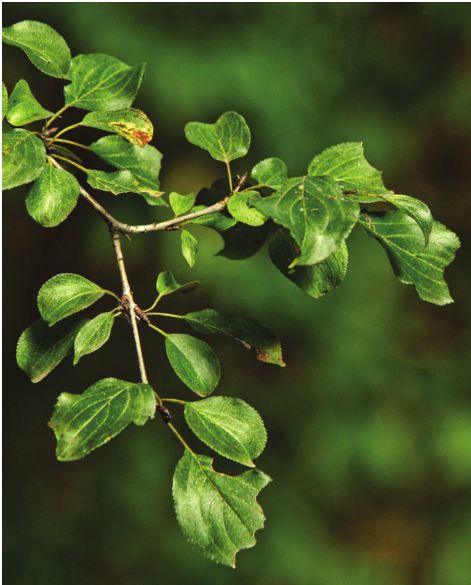

I got to thinking about all this the other day, but not because of our national “debate” about immigration or the admission of war refugees from Syria. I was reading about recent research into the ecological impacts of the shrub known as buckthorn, an aggressive, light-hogging pest. A buckthorn thicket is perfect cover for egg-eating carnivores like coyotes, raccoons and opossums, which is bad news for birds; its leaves contain a toxin that might be causing spinal defects in unborn frogs. Urban wildlife experts have recorded significantly fewer white-tailed deer in buckthorninvaded areas, presumably because in a buckthorn thicket nothing can grow but buckthorn.

I began writing about buckthorn and similar miscreants in the 1980s, most recently in a piece that appeared in the July/ August 2007 issue of Illinois Issues magazine under the title “Romancing the Prairie.” (No longer published on paper, the magazine endures on the web at wuis.org/topic/illinoisissues.) I quote it at length here because what I said then is newly relevant, because most readers probably missed it when it first came out (Illinois Issues circulated mainly among the state government decision-makers and not the wider public) and because I can’t say it any better.

I explained that opportunistic plant species like the buckthorn are known by several generic terms. “Non-native” is the most accurate, followed by “introduced” for those like the buckthorn that were imported for a purpose. “Exotic” carries with it a whiff of the strange; its cousin “alien” adds to that a hint of menace. Most freighted of all is “invasive” and its variants, which hint at malevolent intentions.

There is an unmistakable echo of nativism of the social, human kind (no doubt unconscious) when non-native plant species are so described which hints at the displaced anxiety behind the rhetoric. In his Nature’s Keepers, author Stephen Budiansky quoted a biologist who likened the detestation of exotic plant species to “irrational xenophobia” of the sort that stems from people’s inherent fear and intolerance of foreign races, cultures and religions.

The ecological dilemma faced by the managers of the Chicago area’s forest preserves in the 1970s was very similar to the social dilemma that has always confronted Chicago. William Stevens, writing in his 1995 book about prairie restoration, Miracle Under the Oaks, refers to weedy non-natives as “opportunistic species that run riot in disturbed ground,” and no ground was more disturbed than Chicago where a 19 th century mercantile center was being torn down and a modern industrial city taking its place. In the classic A Prairie Grove (1938), his narrative of the Glenview home of naturalist Robert Kennicott, Donald Culross Peattie wrote with an almost audible relief that the city had not spread out to this little patch of prairie, with the happy result that he did not have “three million neighbors, most of them Italians, Swedes, Poles, Jews, Germans, Hungarians, Czechs, and Negroes.” Immigrants are fine in their place, but that place isn’t in the green suburbs.

One could say – many thoughtful people have – that if invasives create havoc in the green world we got it coming, since most of them thrive in the disturbed environments we have created in city and country. The solution proposed by the egregious Mr. Trump – throw a fence around the United States to keep the newcomers out – is the same solution preferred for decades by nature-lovers, who sought to preserve native landscapes by isolating them in nature preserves. Ecologists are beginning to realize that the answer is not eradication, which is impossible, but to restore some better balance to those disturbed ecosystems in which aliens thrive. A similar approach to reforming our job markets and immigration rules makes similar sense.

Again, anxiety about the effects of newcomers of any kind is natural. While it is almost certainly hyperbolic to talk about immigrants destroying an American way of life that consists in large part of immigrants becoming natives, immigrants will, as they always have, change that way of life. Our Trumps and Cruzes have always made their immigrant anxieties plain. It would be useful if the rest of us, the polite liberals, faced their own anxieties, the better to understand and deal with them. Not all such anxiety is racist or xenophobic, and it would be helpful to sort them out from the simple fear of the Other. If we don’t, we risk turning the public forum into more disturbed ground where weedy untruths will spread.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Editor’s note

For

those of us who don’t understand Donald Trump’s popularity, it was good

to hear President Obama declare for all the world to hear that the

Republican frontrunner is just wrong. In his State of the Union address,

Obama said Americans must resist calls to stigmatize all Muslims at a

time of threats from the Islamic State. “Will we respond to the changes

of our time with fear, turning inward as a nation, and turning against

each other as a people?” Mr. Obama said. “Or will we face the future

with confi dence in who we are, what we stand for, and the incredible

things we can do together?” As we near the end of “hope and change” in

the White House, some of us are hoping for no radical change. –Fletcher

Farrar, editor and publisher