A Christmas memoir

We lived in the country during the 1930s when I was a kid. We would do about the same thing every day, all summer long. Brother Jack and I would run to the front yard when we heard a car approaching, just to watch it go by. We’d stand there awhile and see a big cloud of dust dissipate, and then go back to whatever we were doing before.

I played in Schaad Creek a lot. It ran down the hollow not far from our house. The rippling water running over the sandy and rocky bottom was a pleasure for me to see. It was an ever-changing scene with minnows and crawdads going about their daily business in the sunlit water.

Brother Jack was a little older and had taken the single-shot rifle to go groundhog hunting. Groundhog scalps were worth a quarter apiece in those hard-pressed times. A half a dozen scalps taken to the courthouse for bounty meant real money for a boy.

Mother came out to the creek bank and called down to me that dinner was ready. “Better come and get it,” she said. “Jack is already there.” So I hurried up the path to the yard to find dinner waiting. It was usually potato soup, always with a ring of yellow butter around the edges. Saltine crackers made for a sumptuous meal.

Mother had news for us – the mailman had brought a postcard from Grandma in town. She asked Mom if next week would be a good time for Jack and me to spend a week with her in town. That brightened our spirits quite a lot. We went to town on Saturday night in the huge Ford, parked on the west side in front of Corkey’s Grocery Store. Jack and I went to the picture show while the folks shopped for groceries. We came out of the picture show squinting because of the bright lights.

Then it was time to go to Grandma’s house, just a few blocks away. We boys were excited but tired; it was nearly bedtime. Dad and Mom greeted Grandma with hugs and kisses, unpacked a bundle of clothes to last us the week. The folks visited awhile and were off to return to their place in the country. Since Jack and I were tired; it wasn’t long before we climbed into bed. We slept together in a three-quarter bed, the same bed I was born in six years before.

As

it got very quiet, I could hear a clock ticking. It had a distinctive

“tick-tock, ticktock” coming from the other room. I listened and

listened, and then there was a gong. It gonged 10 times. It was amazing

to me. I whispered to Jack, “Did you hear that, Jack?,” but Jack was

already asleep. I listened to the tick-tock of Grandma’s clock until I

drifted off to sleep.

I

woke up the next morning to the sound of eggs being broken into a

skillet. Grandma would call us to breakfast soon. We got up, hurriedly

got dressed, and were ready when she called. I went into the next room,

the living room, where the clock was. There on a shelf about six feet up

was the clock. I could see the pendulum swinging, with each tick to one

side then the other. I could hardly take my eyes off of it long enough

to eat breakfast.

We

played on the front porch for awhile, sitting on the swing. Grandma

soon stepped out onto the porch all dressed in her churchgoing clothes.

We walked the four blocks to church, went in and were seated. All I

could think about was the clock. Was the clock still ticking when we

couldn’t hear it? Was the pendulum still swinging when we couldn’t see

it? When we got back to the house, the clock was the first thing I

checked on. And yes, the clock still ticked, the pendulum still swung

side to side; it had never quit. When we visited Grandma, I would always

go see that her clock was still ticking and striking the hours, and it

always was. I was always thinking of Grandma’s clock going “tick-tock.”

Dad

was a carpenter by trade. He worked with his brother, Elmo. When the

war broke out in the 1940s the military soon began drafting men for the

service. Elmo had no children; my dad had five kids. Elmo reasoned that

if he enlisted, maybe Dave would not have to go. Elmo was a considerate

man that way, always thinking of others. He joined the

Seabees and was off to training in a few weeks. That left Dad

shorthanded on many jobs. Who could he get to help out with his brother

gone?

There was an

on-again, off-again farmhand living up the road, two or three miles

away. He had an invalid wife and was not so likely to be drafted. His

name was Howard and he had a Model T he could use to get to work. So,

Dad and Howard teamed up. They got along well together and the work

progressed. We were up at Howard’s place one Sunday afternoon. It was a

day for visiting with Howard and his wife, Alma, who was in a

wheelchair. Dad had the kids along and his wife, Marie.

Howard

was showing my dad some shotgun shells he didn’t need anymore. Shotgun

shells were hard to come by with the war going on. There among the half a

dozen shells was an old pocket watch. It was dirty and scratched, but

it caught my eye.

I

pointed it out to Dad. Howard picked it up and right away said, “It’s an

old Ingersoll that doesn’t run anymore. You want it, you can have it.”

Dad said, “Maybe we can get it running again,” and put it in his pocket

with the shells.

Dad

got that pocket watch from Howard’s dresser drawer, but that was all

right. I was just a kid, and at least the watch was in the family. Dad

did take the watch to a jeweler and got it running. I kept asking Dad

what time it was until he finally quit answering me. I don’t know

whatever happened to that old Ingersoll, but it always made me think of

the tick-tock of Grandma’s clock.

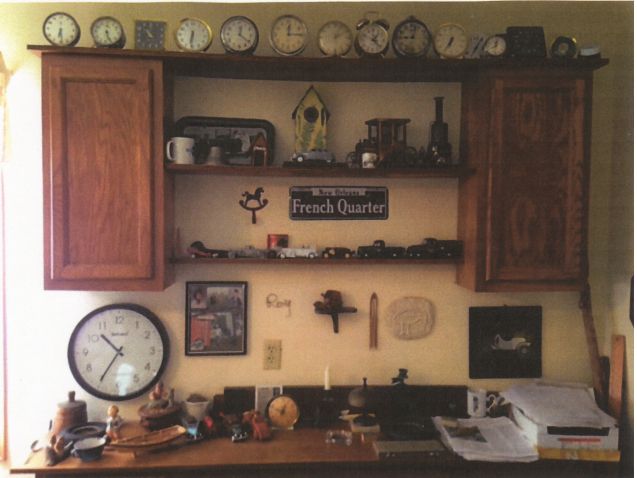

By

the time I was out of the sixth grade I had accumulated several clocks.

I had taken them apart and found that some parts would interchange with

other clocks. I could take parts from one clock and put them in another

clock and make it run again. I had three clocks running on a

shelf near the kitchen. I was proud of my clocks. They were ticking and

tocking back and forth, sometimes together, sometimes not, as if they

were racing. It was all much to my delight.

One

hot summer afternoon during canning season, mother burst out of the

kitchen in a nervous fit and said, “Roy Lee, you’ve got to do something

with these clocks. They are driving me crazy. They tick together and

then they tick apart. I can’t stand it any longer.” I knew she meant

business. I took two of the clocks and put them under my bed. That

quieted them considerably. Now I could drift off to sleep like a ticking

clock. We had peace in the household after that. They quietly

tick-tocked like Grandma’s clock.

I

went to Cottonwood School for my last year of grade school. We had only

eight students going to that small school, four of us were brothers and

sisters. By Christmas, four more students walked out of the timber to

the south. Out of the flooded bottom land came two more boys riding on a

tractor to keep above the high flood waters to make it to school. That

made 14 of us, a pretty good student body for a country school.

The

time of day was kept by a Hamilton eight-day clock, hung on the wall.

If the teacher forgot to wind it on Monday morning, we were at a loss to

know what time it was. So we guessed, and we got by OK. Eventually, the

Hamilton quit keeping the correct time, and that was a problem. The

teacher was only too happy to buy an electric clock. No more winding the

clock – but what to do with the old Hamilton?

I

really wanted to have it. In a day or two, I got up enough courage to

ask the teacher if I could have the old clock, being that it didn’t run

anymore. She said she’d have to think about that. When four o’clock came

she called me to her desk and said, “Roy Lee, if you want the old

clock, I guess you can have it.” I had a big smile on my face and

thanked her profusely. She made me the happiest kid in the schoolhouse. I

grinned as I put the old clock under my arm to walk home. I had another

clock to take apart. It had a pendulum like Grandma’s clock.

I

graduated from the eighth grade at Virginia High School. Mother had

bought me a Westclox Pocket Ben for graduation. She said to me, “Roy

Lee, that watch cost three dollars and ninety-eight cents. I want you to

take care of it. Don’t you try to take it apart. Make it last you a

long time.” And it did. It lasted me all through high school. It lasted

through the summer when I did farm work for a neighbor. It told me when

to come in from the field for dinner and when it was quitting time. It

was a good watch. I could put it to my ear and be reminded of the steady

ticking of Grandma’s clock, see the pendulum swing, see the clock on

the shelf still keeping time.

I

was getting older now. I spent a few years doing carpenter work with

the family, spent two years in the military, a season at the university.

I ran a

lumberyard for five years. From there I went on the road for a large

timber company but I still liked the carpentry work best, and it was

something I was good at. I returned home and took up the carpenter trade

as four generations before me had done.

I

wondered about Grandma after so many years. She had spent some time in a

nursing home and was there again, not doing so well. Mr. Boatman, a

gentleman from across the street, was taking care of Grandma’s clock as

he had done many times before, but this time he had it for three years

or more. One time he showed me how he took a chicken feather, dipped it

in some 3-in-1 oil, and gently brushed the gears and bushings. It must

have worked well because the clock was old and kept good time yet.

Grandma

died a few days later, at 88. In a few days, all Grandma’s children had

come to divide her belongings. Mr. Boatman from across the street was

there with the clock. He placed it gently on the shelf where it had

spent so many years before.

The

first to speak was Uncle Roy. “Being that I am the oldest child here, I

believe I should have first chance at the clock.” Vivian spoke up and

said, “I was the last one born, I think the clock would serve me the

longest, being that I’m the youngest.” Aunt Bessie said that she didn’t

want the damned thing. “It ticked so loud and struck the hour and kept

me awake at night when I was a kid; give it to someone else.”

Uncle

Elmo, always the peacemaker, said he didn’t care who got the clock as

long as it stayed in the family. Aunt Gladys just smiled. Dick left the

room to get away from the squabbling. Dave followed Dick outside. They

stood on the front porch within hearing distance of what was going on

inside; it was getting more heated.

In

a few moments, the screen door opened and out steps Mr. Boatman with

the old Seth Thomas clock, gently carried under his arm. It got quiet,

and he spoke. “I’ve had this clock a few years. I took good care of it,

and now Deana’s gone. I’ll keep it a little longer. When they decide who

should have it, I’ll bring it back.” Nobody got the clock but Mr.

Boatman, and rightly so.

Years

later, I would see Mr. Boatman on the sidewalk uptown. I would ask him

about Grandma’s clock – was it still keeping good time and had anyone

asked for it? The answer was always the same. Yes, it was ticking off

the hours just fine, and no, none of the relations had asked for it.

One

time when Mr. Boatman was in his eighties he saw me walking along the

sidewalk in front of Rexroats Store. He greeted me and said, “You have

asked me about your Grandma’s old clock many times. You seem to be the

only one interested in it. I’m getting along in years, and I think it

needs a new owner.” I said with some surprise, “Do you want me to have

Grandma’s old Seth Thomas clock?” He nodded his head yes. “Mr. Boatman,

I’d love to have it. I’ll give you 50 dollars just to have it back in

the family.” He seemed happy with that. I gave him his 50 dollars and

told him I’d be by in a day to get the old clock. He was very pleased, I

was very pleased. We shook hands and parted.

That

meeting with Mr. Boatman was some 30 years ago. I did get the clock

from him on that following Sunday. I believe it was December, and

Grandma’s clock was a century old by then. It still keeps good time and

strikes the correct hours as it should. The clock has endured a few

moves but it is always put in a special place every time. I wind it on

the first day of December each year and enjoy the tick-tock of Grandma’s

clock and the striking of each hour of the Christmas season. It sounds

as good to me now as hearing it while laying in Grandma’s three-quarter

bed with Brother Jack beside me so many years ago.

Roy French of Virginia, Illinois, 82, has written a Christmas memoir for Illinois Times every year for more than 30 years. His most recent book, The Quiet Woods: Stories, Prose, and Poems from Hickory Hollow, is available for $15 from Roy L. French, P.O. Box 133, Virginia, IL, 62691.