Rail project uncovers evidence of 1908 race riots

When Floyd Mansberger and Christopher Stratton at Fever River Research began their archaeological investigation of 10th Street between Madison and Mason streets in Springfield, they knew the probability was high that they would uncover something significant. Thanks to extensive archival research on this particular site, they had a good idea of who had occupied this block, and why those occupants left. The only question was the status of the site’s integrity, and to what degree the material record would corroborate the written record.

And then, with a few scrapes of the backhoe against the test area, they found it. The foundation of a humble house, which had been home to several working class families over the 60-odd years it stood at that spot. And within the foundation, under a thin layer of yellow silt loam, was the ash that had been deposited the night of Aug. 14, 1908, when that house was burned down by an angry mob during the Springfield race riots. Further excavation revealed the foundations of seven houses, five of which had evidence of being destroyed by fire.

Rail consolidation triggers discovery

The houses were excavated as part of the Springfield Rail Improvements Project to consolidate all railroad passenger and freight traffic from the Third Street corridor to the 10th Street corridor in an effort to reduce congestion, improve safety and enhance livability in Springfield. The consolidation effort is being led by the City of Springfield, in cooperation with Sangamon County and the Illinois Department of Transportation, and managed by Hanson Professional Services, Inc.

The houses were excavated as part of the Springfield Rail Improvements Project to consolidate all railroad passenger and freight traffic from the Third Street corridor to the 10th Street corridor in an effort to reduce congestion, improve safety and enhance livability in Springfield. The consolidation effort is being led by the City of Springfield, in cooperation with Sangamon County and the Illinois Department of Transportation, and managed by Hanson Professional Services, Inc.

One aspect of the consolidation project involves the construction of eight underpasses designed to relieve automobile congestion at railroad crossings. Work began on the first of these underpasses, at 10th and Carpenter streets, after the adjacent land was acquired from St. John’s Hospital in the fall of 2014. The scope of work includes lowering Carpenter Street between Ninth and 11th streets, constructing dual-track railroad bridges, and completing three blocks of draining, grading and sub-ballast south of Carpenter Street.

Because the consolidation project relies in part on federal funds ($152 million of the estimated $315 million price tag), it must obey federal environmental planning and historic preservation laws, including Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, which requires that projects receiving federal funds consider effects on historic properties.

In compliance with Section 106, Hanson contracted Fever River Research to do a Phase I archaeological survey of the land associated with the Carpenter Street project to determine the site’s potential for intact archaeological resources. This initial survey consisted of extensive archival research into maps, census records, city directories and chains of title to determine the history of occupancy on the site.

In compliance with Section 106, Hanson contracted Fever River Research to do a Phase I archaeological survey of the land associated with the Carpenter Street project to determine the site’s potential for intact archaeological resources. This initial survey consisted of extensive archival research into maps, census records, city directories and chains of title to determine the history of occupancy on the site.

Mansberger quickly realized that the area under investigation included the sites of several houses in the area devastated by the Springfield race riots in 1908.

“Our archival research suggested there were a series of houses there that had been destroyed by the race riots. The only question was, would they be undisturbed and intact?” he explained.

Based on their research, the Fever River team identified multiple areas where historic structures had been documented, subsequent ground disturbance appeared to be minimal and the research potential was high. In consultation with the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, it was decided that these areas would be subjected to further archaeological investigation.

At the first test area (Block 3), located along 10th Street between Mason and Madison streets, Phase II investigation of the site began with the excavation of a single backhoe trench. As soon as the trench was opened, however, Mansberger and Stratton discovered the intact structural remains of seven houses. The investigation broadened to a larger block excavation. Each house was mapped, and at least one test unit was dug by hand at each house to assess the depth of the archaeological deposits, the presence or absence of cellars and the nature of the fill deposits in each house.

The second test area (Block 14), located between Mason and Reynolds streets, was subjected to a similar investigation. A backhoe was used to strip the top layer of soil, revealing the remains of two structures dating to the mid-19 th century, as well as several privy pits at the rear of the lot lines. Ten of these privy pits were sampled.

The fragments of the past that are coming to light at these sites paint a fascinating and dynamic picture of the transformation wrought by social changes in 19 th century Springfield.

“It’s the story of an evolution of an urban environment in Illinois,” Mansberger said.

“From a white working class area to an integrated neighborhood to a neighborhood in decline.”

And ultimately, to the destruction of that neighborhood, during one of the darkest chapters of Springfield’s history.

Evidence of a dynamic neighborhood

The

small houses along 10th Street that ended their existence as

dilapidated shacks torched by an angry mob started as the tidy dwellings

of upwardly mobile white working class families built in the 1840s and

1850s. The near north side neighborhood in which they were located

offered affordable housing that was close to the central business

district. The residents of this neighborhood were a mix of nativeborn

Americans as well as German and Irish immigrants. Many of them were

tradesmen (cabinetmaker, hatter, etc), while others worked as millers or

firemen at the nearby Phoenix Mill. Two of the houses were likely

constructed by John Roll, a local building contractor, and operated as

rental properties. Roll was a friend of Abraham Lincoln’s who had also

done work on Lincoln’s house. In 1861, the Lincoln family left their

dog, Fido, with Roll, who had small sons near Willie and Tad’s age.

A

little to the north, in Block 14, were the homes of several Portuguese

families, in an area representing the southern extension of a near north

side neighborhood known as “Little Madeira.” After fleeing religious

persecution in their home island of Madeira, several hundred Portuguese

emigrants settled in Springfield between 1849 and 1852. “Little Madeira”

was one of the earliest and largest Portuguese settlements in the

Midwest [see “When Springfield took in Portuguese refugees,” by Erika

Holst, IT, Sept. 24].

The

project area includes the archaeological remains of two structures. One

is a residence built as a single-family home in the mid-1850s and

converted to a duplex by c. 1860 on a lot owned by Portuguese immigrant

Mary Ferreira. The second is a two-story frame structure that housed a

grocery store on its first level and residential quarters on the second

floor. The grocery story was likely built by Portuguese immigrants John

and Manuel Mendonca around 1867.

Although

the structural integrity of the duplex and the grocery store has been

compromised by 20th century construction, the lots on which they sit

show evidence of several suspected privy pits. Because privy pits served

as garbage receptacles in the 19 th and early 20 th centuries, these

features have the potential yield and exciting array of artifacts that

would provide a wealth of information on the early life and foodways of

this ethnic population.

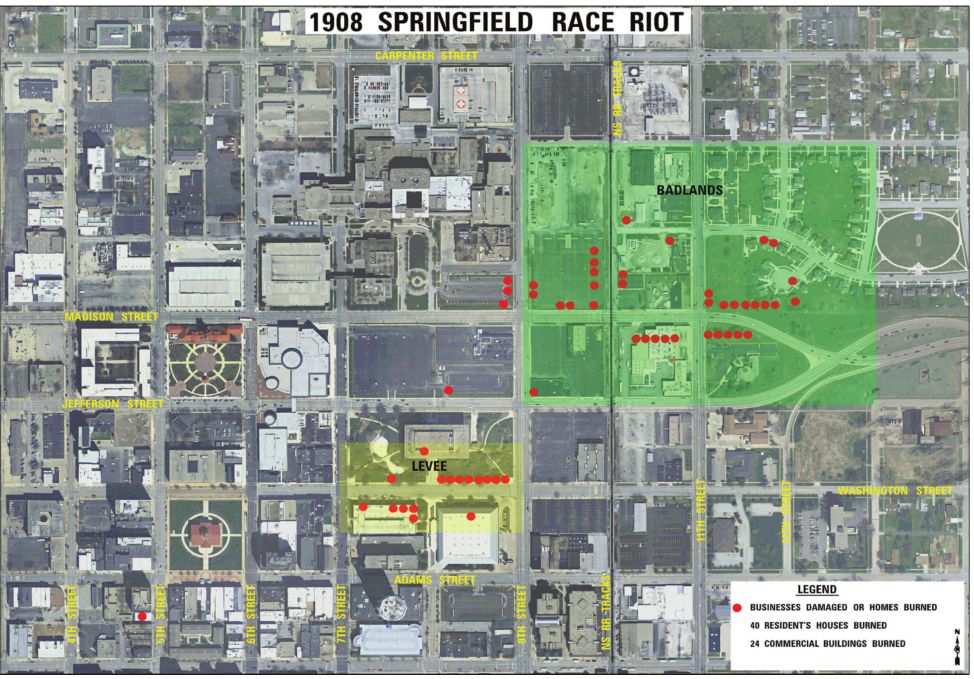

Orgy of violence

By the late 19 th century, the neighborhood represented

in the archaeological project area was in decline, comprised of aging

and dilapidated low-income houses, many of which stood vacant. It was in

an area of town known as the “Badlands,” populated by poor

African-Americans and immigrants. There, in the sweltering heat of

August 1908, longsimmering racial tensions erupted into an orgy of

violence and destruction that reduced more than 40 black-owned homes and

businesses to smoldering heaps of ash.

Tension

had been building in Springfield for years before the race riots broke

out. Springfield’s factories and coal mines drew a large influx of

Southern blacks to the city; native-born white American and European

immigrants alike resented black competition for blue-collar jobs. And in

an era where whites clung to rigid ideas of social and racial

hierarchy, the arrival of a large influx of blacks seemed to threaten

white social and economic dominance.

This simmering racial tension reached the boiling point on Aug.

13, 1908, when 21-yearold Mabel Hallam claimed that a black man had

crept into her home, dragged her from her bed and assaulted her. She

identified her assailant as 36-year-old George Richardson, a laborer who

had been working in Hallam’s neighborhood. Despite Richardson’s

protests that he had been at home with his wife when the attack took

place, he was arrested and taken to the Sangamon County jail.

The

public was outraged at the alleged crime. The idea that a black man

would assault a white woman was the specter that haunted many a white

supremacist nightmare, and countless acts of racially motivated violence

against blacks have been perpetrated in the United States in the name

of protecting white women’s honor.

The

public was outraged at the alleged crime. The idea that a black man

would assault a white woman was the specter that haunted many a white

supremacist nightmare, and countless acts of racially motivated violence

against blacks have been perpetrated in the United States in the name

of protecting white women’s honor.

On

Aug. 14, not long after Richardson’s arrest, a vengeful crowd gathered

outside the jail building, their mood growing darker as the hours crept

by and the mercury in the thermometer rose. Knowing that there was a

real possibility the crowd might try to forcibly drag Richardson out and

lynch him, the sheriff, Charles Werner, arranged to have Richardson and

another black prisoner spirited out of the jail and put on a northbound

train to Bloomington.

The

crowd’s temper was not improved by the realization that the objects of

their vengeance had been spirited away. They milled about uncertainly

for a time, then were energized by the news that restaurateur Harry

Loper had loaned his car as the getaway vehicle. With shouts and

threats, the crowd made its way south to Loper’s restaurant.

After

an hour-long standoff with Loper, who stood in the door of his

restaurant with a loaded rifle, violence erupted. Loper’s car, parked in

front of the restaurant, was turned over and set ablaze. A brick was

sent crashing through the restaurant’s plate glass window. Amid shouts

of “curse the day that Lincoln freed the niggers,” the mob rushed into

Loper’s establishment and utterly demolished it, smashing tables chairs,

plates, glasses and mirrors.

The

flame of violence, once ignited, was not readily extinguished. From

Loper’s restaurant, the crowd moved on to the Levee, a red-light

commercial district along East Washington Street which housed several

black-owned businesses. There they laid waste to whole blocks of

black-owned businesses, being careful to spare property owned by whites.

The Journal reported that “within a short time the east end of

the levee was the scene of a brilliant illumination which cast its

baleful glare over the entire city.” When firemen tried to put out the

blaze, the mob promptly cut their hoses. Weapons were fired with

impunity, resulting in dozens of injuries and a handful of deaths.

Finally,

the mob moved on to the Badlands, where it continued its hellish

devastation. Torches were applied to black-owned homes, while those of

whites (indicated by white handkerchiefs) were spared. According to the Journal, “terror-stricken

men and women rushed from the houses and fled for their lives, with

frenzied whites in wild pursuit.” A black barber named Scott Burton was

beaten senseless, dragged from his home, and lynched from a dead tree;

his body was then riddled by bullets and slashed by knives.

By

the time the riots were finally quelled by the state militia on

Saturday, Aug. 15, two black men had been killed by the mob, five white

men had died of wounds sustained during the melee and more than 100

people had been injured.

One

of them was a black man named William Smith, of 301 N. 10 th St. The

newspaper reported that Smith was “tied to telegraph pole and face

beaten to jelly.” The foundation of the house where Smith lived was one

of those unearthed by the Carpenter Street underpass archaeology. The

stoop across which Smith was dragged from the safety of his home by a

violent mob survives, preserved under the earth for more than a century.

Deposits of ash and charred artifacts within the foundation testify

that Smith’s house was destroyed by fire even as he underwent physical

assault in the riots.

In the aftermath of the riot, the Journal reported that “on both sides of 10th Street north of Madison Street, there were a row of huts, which were destroyed

by the torch of the mob.” Thanks to archaeological investigation of the

Carpenter Street underpass, we know that there were five houses in that

row, plus two adjacent that escaped destruction. These sites,

undisturbed archaeologically for more than a century, represent a

horrific moment frozen in time.

“The

fact that this block largely was cleared of housing in one devastating

event and never reoccupied, presents a unique opportunity to examine one

enclave of African-American residents at one pivotal point in time,”

Mansberger and Stratton wrote in the site’s executive summary. “The

houses and their contents can be considered part of the forensic

evidence of what was in essence a crime scene.”

The future of the site

For now, excavation at the sites has halted.

The

features were filled with sand and covered with geotextile fabric to

prevent erosion and the site is fenced and monitored by security

cameras. These actions were taken on the recommendation of the Illinois

Historic Preservation Agency to secure the site until a federally

mandated consultation process determines appropriate treatment or

mitigation for the cultural resources contained within.

The

significance of the findings at the Carpenter Street underpass site

means that the project area meets criteria A and D for inclusion on the

National Register of Historic Places as defined by the National Park

Service. Criterion A includes places “that are associated with events

that have made a significant contribution to the broad patterns of our

history.” This criterion is met by the site’s association with the

Springfield race riots, which had a direct role in the formation of the

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) the

following year. Criterion D, which includes places “that have yielded,

or may be likely to yield, information important in prehistory or

history,” is met by the site’s potential to reveal material evidence of

the evolution of an urban environment as well as the race riot.

Because

it meets these criteria, the site is currently subject to the review

process stipulated by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation

Act. Major participants in the Section 106 process include the Federal

Railroad Administration, the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, the

City of Springfield and the federal Advisory Council on Historic

Preservation.

As part

of the review process, a series of open meetings were held to give

members of the public a chance to learn about the project and provide

their views. Individuals or organizations with a demonstrated interest

in the project were invited to become “consulting parties,” who will be

involved in the plans for the management of the site’s cultural

resources as the rail consolidation goes forward.

Kevin

Seals, chief environmental scientist at Hanson Professional Services,

explains: “When you have a protected resource, you want to first avoid

[impacting] it, then minimize the impact on it, then mitigate for it. If

impact can’t be avoided or minimized, then we would mitigate.”

Rev.

T. Ray McJunkins, pastor of the Union Baptist Church and cofounder of

the Faith Coalition for the Common Good, is dismayed by the prospect of

the archaeological site being destroyed by railroad tracks.

“In

that case, there’s nothing you can do to memorialize this as an

historical site. When someone wants to visit this site, all they would

see would be railroad tracks,” he said. McJunkins would like to see

further excavations done on the site and the planned tracks adjusted to

accommodate the site.

“Let

us not forget the history of Springfield. The race riots are a part of

that history. More should be done to interpret that story than a marker

placed at a site that isn’t even the actual site of the event,”

McJunkins said.

As

currently conceived, the 10th Street rail consolidation plans call for

the new railroad right of way to go directly over the seven excavated

house foundations. The “consulting parties” sent a letter to Union

Pacific asking the railroad to alter its footprint to avoid the

archaeological features. They are still awaiting a response.

In

the meantime, the “consulting parties” are weighing in on the best

course of action to protect the site, mine its information and share

that information with the public.

Frank

Butterfield, Springfield field office director for Landmarks Illinois,

said “Through community engagement and the consultation process, we hope

to find a solution that minimizes disturbance to this historically

significant site. Our local partners continue to explore ways to

protect, share and interpret the archaeological site and the information

that has been gathered from this ongoing process.”

Suggestions

include erecting a historical marker on the site, conducting further

archaeological excavations of the site, and creating a traveling

exhibition of artifacts recovered from the site.

Fortunately,

the archaeological site is in no immediate danger. Construction of the

railroad right of way will not begin until all eight underpasses have

been built, a process which will take several years. Because the

archaeological discoveries are several blocks away from the Carpenter

Street Underpass, work on that project is proceeding on schedule.

Ultimately,

the city of Springfield has reaped cultural benefits from the railroad

consolidation project because of its use of federal funds. Had the site

in question been under private development, the cultural resources it

contained could easily have been destroyed with no one being the wiser.

As

it is, the excavation has brought to light new information on the

evolution of Springfield as a 19 th century urban environment as well as

on a pivotal, if tragic, moment in this city’s history.

Erika Holst is an historian and author. She is Curator of Collections at the Springfield Art Association.