Short-staffed jewel withers

While tourists bustled in and around the museum side of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum on a recent summer day, the library portion was quiet.

Just two people perused newspapers in the Steve Neal Reading Room, named after the late Chicago Sun-Times columnist who crusaded against the ALPLM becoming a patronage dump even before the institution opened a decade ago. Such titles as The Encyclopedia of World History and Index of Revolutionary War Pension Applications sat alongside each other on shelves, hinting at the breadth of the library’s collection while serving as a reminder that this place is supposed to be about a lot more than Abraham Lincoln. Corridors were empty, nearly bereft of exhibits or displays.

The library side of ALPLM is also the state’s historical library, which celebrated its 125 th anniversary last year. Beyond collecting documents connected to Lincoln, the library holds the papers of less-remembered people such as Joseph Ragen, warden of the nowclosed penitentiary in Joliet who proclaimed it the world’s toughest prison after he took over in 1936 and ran the place so well during his 25-year tenure that Europeans came to Illinois to learn how to keep inmates locked up.

The library is packed with 12 million letters, diaries, business records, personal papers and other documents connected to governors, legislators, soldiers, sundry bureaucrats and just regular folks. There is Depression-era stuff penned by authors employed by the Federal Writers Project, documents from the AFL-CIO and an estimated 400,000 photographs, drawings, posters and other visual images. There is footage from Adlai Stevenson presidential campaign television commercials as well as sheet music, including the words and music to “We Are The Gay And Happy Suckers Of The State Of Illinois,” a Civil War ditty sung by Union troops from the Land of Lincoln.

It is a veritable warehouse of the state’s history. But relatively few people come here compared with the museum next door that attracts more than 300,000 visitors each year. Fewer than 5,000 people visited the library to access its collection last year, according to the ALPLM’s annual report issued in March. The library’s importance, however, cannot be measured by turnstiles.

Without the library, the museum would not be much more than a collection of rubber Lincolns and Disney-esque dioramas. The library is home to the vault that contains treasures that provoke awe, such as Lincoln’s bloodstained gloves from Ford’s Theater as well as copies of the Emancipation Proclamation and the Gettysburg Address. It’s a must for serious Lincoln scholars interested in less-famous documents.

“My feeling is, you cannot write a book about Abraham Lincoln that embraces his life before Washington without going there, without absorbing the materials, without looking for things and without looking for things you don’t know you’re looking for,” says Harold Holzer, a historian and author who has written and edited more than 30 books about

Lincoln and the Civil War. “You can go from one stack of papers to

another and find one set of papers from another set that you didn’t know

existed. It’s that sense of discovery that you can only get from doing

research that you can’t do online and that you can only do with original

papers.”

Unlike

some other libraries, the presidential library welcomes inquiries from

researchers, Holzer says. The staff, he says, genuinely wants to help.

“There

are archives where people act as if the worst thing that ever happened

is when someone walks into a room and asks for something,” Holzer says.

“There are people who act like guardians, not like sharers. Springfield

shares. There’s no other place like it.”

But there are also some troubling signs.

A skeleton staff

“The

newspaper microfilm section will be closed at 3:00 p.m. today,” reads a

note attached to the door of the room where copies of every newspaper

in the state are supposed to be preserved on microfilm. “We apologize

for the inconvenience we have caused, as we are short staffed.”

Inside the department, the newspaper microfilm collection is filled with gaps. Want to see a copy of the Bloomington Pantagraph from

1866? Unless you’re looking for the paper published on May 16, 1866,

there aren’t any. Try the Bloomington Public Library, where you can read

almost every issue of the Pantagraph published since 1853 on

microfilm readers that are nearly as easy to use as computers. Making

copies is a snap. By contrast, the behemoth microfilm readers at ALPLM

would be familiar to anyone who went to high school when Jimmy Carter

was president.

The Springfield public library is miles ahead of the presidential library when it comes to preserving the State Journal-Register and

other daily newspapers published in the capital city. Copies of

Springfield newspapers dating back to 1831 are digitized, available

online and searchable with key words via the municipal library. ALPLM

uses microfilm and so researchers must visit in person between 9 a.m.

and 5 p.m., Monday through Friday. Unlike the neighboring museum, the

presidential library is closed on weekends.

The newspaper microfilm department isn’t the only one not running at full strength.

“I

am currently working in the stacks,” reads a note attached to the door

of the library’s audio visual department. “If you want to use the audio

visual department, please check back in an hour.”

Try calling the library’s cataloguing department and you’ll get a recorded message.

“Sorry, Jane Schmidt is not available.

Record your message at the tone.”

Schmidt,

who worked as the library’s cataloguer, will not be available for quite

some time. She retired in May and has not been replaced.

Want to donate something to the library? Good luck reaching

someone in the acquisitions department since Gary Stockton, the

library’s acquisitions chief, left this summer.

“Mr.

Stockton has now retired,” a recorded message informs callers. “At the

present time, professional calls for acquisitions will now be taken by

the ALPLM executive director.”

Just

how deeply the staff has been cut is tough to determine, given that the

Illinois Historic Preservation Agency that runs the library says that

it doesn’t have an employee list from 2004, when the library opened. But

Kathryn Harris, the library’s former director who retired last spring

and has not been replaced, says that the staff has been reduced, mostly

through attrition, since the very beginning.

“I am very confident that we are at less than half of the staff that we had when we started,” Harris says.

And

so service has been reduced while work backlogs grow. In the newspaper

microfilming department, the backlog stands at one year, Harris said.

Someone who brings in a newspaper to be microfilmed – the library relies

on donors to fill in gaps – can’t expect to see it preserved anytime

soon.

“We sadly have to tell them, ‘It won’t be filmed by next week but come back in 52 weeks – it might be filmed,’” Harris says.

The library stands in stark contrast to the Illinois State Library, which is run by

the Illinois secretary of state and also holds historic documents as

well as federal documents, maps, manuscripts and tens of thousands of

books, with an emphasis on government and public policy. The state

library has 5 million items, less than half the number of items kept in

the presidential library, and 77 employees. The state archives, also

run by the secretary of state, employs an additional 49 people who

preserve and maintain records of state and local governments dating to

the 19 th century.

The

presidential library has 23 employees, according to the institution’s

website. And that number could be reduced even further, given that the

IHPA has not renewed a contract with the University of Illinois

Springfield that established at least nine positions within the Papers

of Abraham Lincoln project, which is housed at the library and has a

goal of digitizing every paper seen by or written by Lincoln.

Harris says that requests for new employees consistently went unanswered while she was library director.

“After

a while, when I felt I was seeing that this is how this is going to

work, I just quit asking when people left,” Harris recalls. “I got tired

of hitting my head against a brick wall.”

“I am working in an awful place”

Gwenith

Podeschi, the sole remaining reference librarian at ALPLM, clearly

loves the library. You can tell by the way her voice cracks as she

describes what it once was and what it has become.

“I am working in an awful place,” Podeschi says.

Podeschi

once thought that working at the presidential library would be the

pinnacle of a career that included nine years as director of the

Taylorville Public Library and a year as a librarian at the U.S. Court

of Appeals in Springfield. She has been at the presidential library

since the day it opened in 2004. Back then, Podeschi worked alongside

another reference librarian, plus two cataloguers and an acquisitions

archivist.

“That

was this department alone,” Podeschi recalls. “It was wonderful. We

actually had a staff. Now, all we have is a manuscript cataloguer.”

And

so Podeschi often finds herself cataloguing maps, books and sundry

historic treasures. It’s precise work, she says, a far cry from taking

inventory of books by Danielle Steel. Cataloguers in historical

libraries must note the number of pages in an item. If it’s a map, it

must be measured. Details are important.

“I

cannot sit at a computer and do the kind of fine, detailed work that

needs to be done with cataloguing – especially cataloguing at a

historical library – then be interrupted to talk to someone about their

ancestor who was killed at Gettysburg,” Podeschi says.

The lack of cataloguers has real consequences. Until books and other items are catalogued, they can’t be accessed by the public.

“I

have a whole wall of books upstairs already that can’t be catalogued,”

Podeschi says. “I don’t have the expertise to do it. … We get a complete

song-and-dance from the director anytime we mention we’ve got to have a

cataloguer. ” The Illinois State Genealogical Society provides the

library with $2,000 a year to buy books, Podeschi says, but that money

has gone unspent.

“I can’t order new books,” Podeschi says.

“I don’t have the time to pick them out. If they got here, they couldn’t be catalogued.”

Chris

Wills, IHPA spokesman, says that the library relies on donations to

build its collection and spends about $1,000 a year on acquisitions.

During

a brief conversation after a chance encounter in the library, Eileen

Mackevich, ALPLM director, acknowledged that the library lacks

cataloguers. She agreed to an interview, then canceled an appointment.

Asked via email when she would be available to speak, either by

telephone or in person, Mackevich made no promises.

“Will

let you know,” she wrote. Meanwhile, Podeschi makes plans for

retirement. She said that she had planned on working at the ALPLM for at

least three more years, but she now plans to leave next June.

“At

my fingertips at any one time in a day, I can handle material worth

tens of thousands of dollars and answer questions no one else can

answer,” Podeschi says. “No one seems to understand that this treasure

is worth holding onto. … As a professional, as someone who has always

liked history and who loves this state, I can’t stand to watch this any

longer. I’ve just got to get out.”

No easy answers

That the library’s staff has dwindled is no secret.

Last

December, Mackevich told the institution’s advisory board that

retirements coupled with no plans to replace outgoing workers has put

the library in jeopardy. The institution would have to make “hard

decisions” about what services can be provided in the future, Mackevich

told the board. The library’s staff

during the past year has focused on what programs and services could be

eliminated, according to the ALPLM annual report issued last March.

“I

think there’s a key problem with the library with understaffing –

that’s been a systemic, longstanding problem, from what I can tell,”

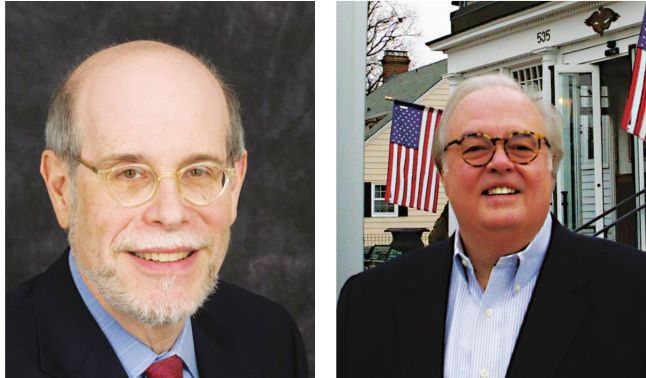

says Patrick Reardon, an author and former writer for the Chicago Tribune who

sits on the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Museum Advisory Board,

which has the power to recommend improvements but no authority to carry

them out. “They’ve got this pile that just keeps getting bigger, an

inbox that never gets cleared.”

The

advisory board, Reardon says, has been told that money for the library,

where admission is free, depends on attendance at the museum, which

sells tickets. And museum attendance has been dropping over the years.

“The

library is, in a way, like the tail of the dog – it’s perceived that

way,” Reardon says. “It’s real easy to lose sight of the reality of how

precious the materials in the library are. If you didn’t have the

library, you wouldn’t have most of the stuff that you’d want to put in a

museum and you wouldn’t know quite what to say about Lincoln. We

shouldn’t get into a situation where we’re saying the library’s more

important than the museum or the museum is more important than the

library. They’re intertwined. They’re the same person.”

Reardon

doesn’t have a simple solution. “There’s nothing that can be done

easily,” Reardon says. “We need to recognize how important this is in

the context of all the other important stuff and aggressively find

funding, whether it’s the state or outside sources, that will beef up

staffing at the library.”

Tony

Leone, a former member of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency

board that oversees ALPLM and has the authority to set policy, says that

the state library should take over the presidential library. When first

conceived, Leone said, the presidential library was supposed to get

funding from the institution’s private nonprofit foundation, which is

now struggling to pay off a loan used to acquire artifacts for the

museum.

“The

foundation has failed to establish an endowment,” Leone says. “With the

state cutbacks, you’ve got to look at a different model.”

“ No one seems to understand that this treasure is worth holding on to.”

The state

library, Leone says, already has an administration in place to take care

of overhead costs. It also has alliances with libraries throughout the

state to allow for interlibrary loans and other collaborative projects,

and so the state library could make what’s now in the presidential

library more accessible to people outside Springfield, he said. Items

related to state history that have no connection to Lincoln should be

separated from the presidential library so that they don’t get

overshadowed by the Great Emancipator, with the state library deciding

the best places to keep items, either inside or outside the presidential

library.

“If you need

to downsize the number of employees, you need to consolidate it under

one administrative body,” Leone said. “The big plus with the state

library is, it has this wonderful network with all the libraries

throughout the state of Illinois. Taking all of the Lincoln stuff and

keeping it together and taking all of the non-Lincoln stuff out of the

presidential library and museum, with everything under the state

library, just makes a ton of sense. You’ve got to put everything under

the expert. The expert is the state library.”

Harris,

the retired presidential library director, says that Leone’s idea isn’t

workable. Elected officials, she says, don’t easily surrender turf.

“The

(presidential) library is under the auspices of the governor, the

Illinois State Library is a department of the secretary of state,”

Harris says. “I can’t imagine either of those constitutional officers

willingly giving up any of their departments.”

In limbo

While

the library withers, those responsible for developing policy and

running the place say they can’t predict the future due to spats about

governance that became public in the spring of 2014, when House Speaker

Michael Madigan, D-Chicago, sponsored a bill to remove the library and

museum from IHPA and make the institution a standalone agency. The bill

brought to the surface longstanding tension between IHPA director Amy

Martin and Mackevich, the ALPLM director, with both women claiming

authority to make decisions about ALPLM staffing and operations.

Senate

President John Cullerton, D-Chicago, is holding a bill passed in May

that would separate the ALPLM from the historic preservation agency.

Rikeesha Phelon, Cullerton spokeswoman, said that the Senate president

is holding the bill due to a threatened veto from Gov. Bruce Rauner, who

has linked governance changes to his plan to privatize the Department

of Commerce and Economic Opportunity. The governor’s office did not

respond to a request for comment.

“We’re

in limbo,” says Steve Beckett, chairman of the ALPLM advisory board

that makes recommendations on how the institution should be run. “I’ve

got board members saying ‘Are we meeting, are we not meeting?’ It’s just

goofy.”

The IHPA

board to which the advisory board reports is in a similar position,

according to IHPA board member Ted Flickinger. The current board would

be dissolved under the bill now being held by Cullerton.

“We

haven’t had a board meeting in months, ever since the question on the

status quo, whether there’s even going to be a board, came up,”

Flickinger said.

Rauner

during his state of the state speech in February said that he supported

separating ALPLM from the historic preservation agency. State Sen. Andy

Manar, D-Bunker Hill, who sponsored the bill to make the ALPLM a

standalone agency, said that Rauner last spring threatened to veto the

bill because lawmakers put a sunset provision on legislation that would

privatize parts of the Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity.

The

presidential library and museum would benefit if they were a standalone

entity because they now compete for staff and money with other parts of

the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency, which is in charge of

historic sites throughout the state, Manar said.

“The

current structure is not serving the ALPLM well,” Manar said. “We have,

in Abraham Lincoln, perhaps the greatest president in U.S. history.

State government ought to be treating it as such. And today it doesn’t.”

But Podeschi, the reference librarian, said that fights over governance mask the main issues.

“We

should all be working together,” Podeschi said. “We need a library

services director now, and we need one who will lay it out: This is what

we have to have to make this library function again. We need to move

beyond crisis mode.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].