History of the Jewish community in Springfield

Springfield’s original Jewish settlers arrived in the city in the 1850s. Some of them moved into Springfield from the surrounding small towns, where they had lived previously. Early immigrant Jews frequently began working as peddlers, selling dry goods, notions and household items to the rural population, and then settled down and opened general stores in the small towns. Athens, Salisbury, Petersburg and Ashland were some of the towns where Jewish families lived at the time.

Origins Organized Jewish life began in 1858 with the founding of the Springfield Hebrew Congregation. The members of the congregation were predominantly immigrants or the children of immigrants from Germany. Early Jewish settlers included the Myers, Salzenstein, Hammerslough and Rosenwald families. They are buried in Block 6 in the northern part of Oak Ridge Cemetery, one of three sections at Oak Ridge set aside for the Jewish community over the years. Within a few years of its founding the congregation came to identify with the Reform Jewish movement, which had become the dominant expression of Judaism in the 19th century German-Jewish immigrant community in America. Reform emphasized Judaism’s ethical teachings and deemphasized ritual and ceremony, breaking with many of the traditions of Jewish Orthodoxy. In 1876, the congregation built a synagogue on North Fifth Street between Mason and Carpenter and changed its name to Temple B’rith Sholom (“covenant of peace”).

Between 1880 and 1920, some two million East European Jews came to the United States from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires and from Romania to escape poverty and oppression. “Russian” Jews, who came from Ukraine, Belarus, Latvia, Lithuania and parts of Poland, especially suffered persecution and discrimination under the Czarist regime and came to America seeking freedom and opportunity. East European Jews began arriving in Springfield in the 1880s. They didn’t have a synagogue building at first and met for services in rooms either behind or above their businesses. The Fishman and Greenberg families were among the early East European Jews to come to Springfield. Some families may have come to Springfield because Jewish organizations in the East were endeavoring to disperse the Jewish population and had sent them to the “hinterlands”; others came because members of their extended families or townsfolk from their East European communities were already here. A sizable number of Springfield Jewish families had their origins in the Rovno (or Rivne) region of Ukraine in the towns of Yampol, Zaslav, Belogorodka and Shepetovka.

In 1895, East European Jews purchased a former Methodist Church on the southeast corner of Seventh and Mason streets and adapted it for use as a synagogue. The congregation was named B’nai Abraham, and its ritual was Orthodox (worship based on the unabridged traditional prayer book and totally in Hebrew; men and women seated separately). The congregation did not have a rabbi until the late 1920s, and religious leadership was exercised by learned men who could conduct the traditional Hebrew prayers. The most important religious functionary was the shochet, the ritual slaughterer, who was able to kill poultry and cattle in keeping with the Jewish dietary laws. A shochet often combined that function with the position of chazzan, the cantor who chanted the prayers. Rev. Manuel Bass served for many years as the shochet for the Orthodox Jewish community.

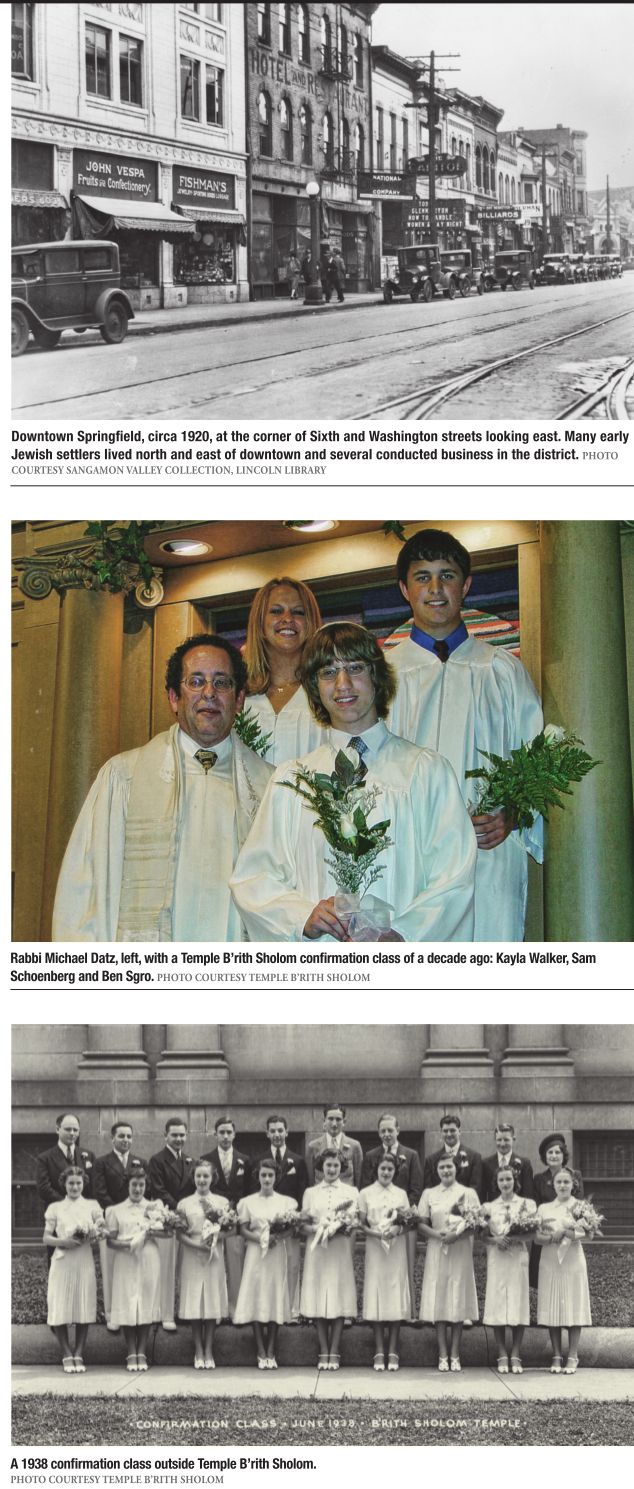

The more prosperous German Jews had begun to move during the first decades of the 20 th century to the Aristocracy Hill neighborhood south of downtown. Between 1915 and 1917, Temple B’rith Sholom built a new synagogue in the Classical Revival style on South Fourth Street, which it still uses. The East European Jews lived north and east of downtown on Jefferson, Mason, Reynolds and Carpenter streets. Many of them had businesses along Washington Street from Sixth Street east. Jewish-owned businesses included pawn shops, small department stores, shoe repair and tailor shops, and stores specializing in sporting goods, miners’ supplies, furniture, work clothes and men’s and ladies’ apparel. There was usually at any given time a Jewish deli and a kosher butcher shop in operation. The scrap metal or “junk” business was one in which Jews were dominant throughout the country, and Springfield had a number of such enterprises. The Barker-Lubin Builders’ Supplies business (originally Barker-Lubin-Goldman) enjoyed its initial success when it was given the contract to dismantle the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair.

Despite the Great Depression, both congregations

flourished in the 1930s. Illinois during that time had its first Jewish

governor, Henry Horner. (Samuel Shapiro was its second and only other.)

Some of the more prosperous members of B’nai Abraham moved from the

near north side to the Washington Park area on the west side of town.

B’nai Abraham’s first two rabbis, David Tamarkin and David Winchester,

who served during the late 1920s, were succeeded by Rabbi Louis Cardon,

who led B’nai Abraham from 1933 to 1947. Rabbi Herman Snyder served

Temple B’rith Sholom from 1929 to 1947. Both served in the military

chaplaincy during World War II. Rabbi Cardon spearheaded the

construction of a social and educational building adjacent to B’nai

Abraham’s synagogue, which was completed in the late 1930s.

Second-generation

Jews, by and large, stayed in Springfield and continued to work in the

family-owned businesses, although some did get law degrees. American

Jewry was predominantly endogamous (“in-married”) until the 1960s, and a

large number of Springfield Jewish families were related to each other

through marriage. A newly arrived member of the community had to refrain

from gossip, because one couldn’t be sure the person about whom you

were speaking wasn’t the listener’s brother- or sister-in-law. The

Illinois Federation of Jewish Youth (IFJY) brought together Jewish teens

from Springfield, Decatur, Peoria, Danville, Champaign and Bloomington,

and was responsible for any number of marriages.

Most

of the Jewish young men (and some women) of service age were in the

Armed Forces during World War II; six were casualties of the conflict.

During

the late 1940s and early 1950s, there was talk of a merger or, at

least, a sharing of facilities between Congregation B’nai Abraham and

Temple B’rith Sholom and a joint move to the Pasfield Park area on the

west side of Springfield. Differences in ritual between the

congregations were more pronounced than they are today, and passions ran

high. The merger talks fell through, however, and the congregations

each embarked on their own separate building programs. Rabbi Meyer

Abramowitz came to B’rith Sholom in 1957 and served as the

congregation’s spiritual leader for 20 years. The congregation’s

Memorial Building just south of the Temple was completed in 1958 and

provided classroom, office and library space as well as a large

fellowship hall.

In

the early 1950s, a violent storm blew the roof off of B’nai Abraham’s

synagogue. The congregation continued to meet and to worship in the

adjacent educational building, but a move to the west side, where most

of the congregants now lived, was clearly in the offing. In 1957, five

members of B’nai Abraham donated a parcel of land on Governor Street

between Lincoln Avenue and Illini Court for the construction of a new

synagogue. The congregation was rechartered as Temple Israel and

identified itself as a conservative congregation (still traditional in

its practices but somewhat less rigorous than

Orthodoxy

in its application of the rules). This was a difficult period in the

congregation’s history with religious education and worship services

taking place at various rented locations around town (DuBois School and

Springfield Theatre Centre – now Legacy Theatre – on Lawrence Avenue

among others). The new building was completed in 1961, and the

congregation began to enjoy a more stable existence.

Rabbi

Barry Marks, who came to Temple Israel in 1973, was the fourth rabbi to

serve the congregation at its new location and has been with the

synagogue for more than 40 years. B’rith Sholom has also had a

long-serving spiritual leader, Rabbi Michael Datz, who came to the

congregation in 1992, and has served for 23 years.

Modern

times The 1970s were a period of growth for the Jewish community. The

founding of Sangamon State University (now University of Illinois

Springfield) and Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, as

well as the expansion of Illinois state government, brought many young

Jewish professionals from out of town (especially from the Chicago and

St. Louis areas) to Springfield. Newcomers contributed their talents to

local Jewish organizations and enhanced their vitality. Members of the

Jewish community have been prominent in the legal and medical

professions as well as in the leadership of local community

organizations.

In

1981, the two congregations merged their Sunday school programs and

formed the Springfield Board of Jewish Education to administer the joint

enterprise (midweek Hebrew instruction had been merged four years

earlier). The joint school at one point had more than 100 students but

now has a student body of only 18, a sign of the declining Jewish

population and the aging of the local community. Temple Israel and

Temple B’rith Sholom cooperate in other joint endeavors as well.

Jews

constitute a religious community but, additionally, have a sense of

peoplehood, a sharing of common history and common destiny with Jews

around the world. Since World War I, the American Jewish community has

assumed a role of leadership within world Jewry and felt a sense of

responsibility for endangered or threatened Jewish communities around

the globe. The Holocaust (1939- 1945) and the establishment of Israel

(1948) have been the two events that have shaped the consciousness of

Jews in modern times. The Jewish Federation of Springfield was founded

in 1941 as the charitable, cultural and philanthropic arm of Springfield

Jewry and the umbrella organization representing the entire Jewish

community. The Federation raises money for Israel and for assistance to

Jewish communities in need, runs local programs for seniors and for

youth, sponsors adult education, and coordinates the community calendar.

For 30 years, the Federation ran a weekly kosher lunch for seniors as a

branch of the local Daily Bread program. The Federation has been ably

led over the years by its executive directors Dorothy Wolfson, Lenore

Loeb, Gloria Schwartz and Jo Gon. Members of the local community have

served in national leadership as board members of the Jewish Federations

of North America and the Jewish Council for Public Affairs.

The

Jewish Community Relations Council, funded by the Federation and made

up of representatives from each of Springfield’s Jewish organizations,

advocates on behalf of Israel, participates in local programs addressing

poverty and hunger, maintains contact with the administration of area

school districts, sponsors teaching training relating to the teaching of

the Holocaust, fights racism and anti-Semitism, and promotes congenial

relationships with other groups in Springfield (African-Americans,

Latinos, Indians, etc.). A major focus of Federation and JCRC activity

in the 1980s was advocating for the human rights of Jews in the Soviet

Union and particularly for the right to emigrate freely from the USSR.

When the gates were finally opened in the early 1990s, the Federation

was responsible for resettling several dozen Jewish families from

Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova and other former Soviet republics.

This was a major effort involving housing and employment for the

newcomers as well as familiarizing them with the American way of life.

Other

local Jewish organizations include a chapter of Hadassah, a national

women’s organization whose main mission is to support the Hadassah

Medical Center in Israel, and a local lodge of B’nai B’rith, a men’s

fraternal organization that dates back to the mid-19 th century.

Early

anti-Semitism Anti-Semitism was a sad reality in early Springfield

history. Jews formerly were barred from membership in Springfield’s

Sangamo Club and Illini Country Club. When I arrived in 1973, Jews had

been admitted to the Sangamo Club for some time, but Illini was still

maintaining its discriminatory policies. Some local employers had few,

if any, Jewish employees in their workforce and were suspected by the

local Jewish community of discriminating. In the late 1980s, conflict

between Israelis and Palestinians led to some dark manifestations of

anti-Semitism. Rabbi Marks received threatening anonymous phone calls,

and Temple Israel’s windows were defaced with the spray-painted words,

“Burn Jews.”

Overt

hostility now seems to be a thing of the past. What we encounter today

might be more accurately characterized as insensitivity (a minister

praying “in Jesus’ name” at a gathering where non-Christians are in

attendance; a store clerk asking a Jewish child what s/he wanted for

Christmas; the scheduling of a public school or community-wide event on a

major Jewish holiday). Even here, progress has been made, and there are

sincere attempts to be inclusive and to recognize the diverse nature of

Springfield’s population.

What

largely concerns Jews today are issues relating to Israel: the Boycott,

Divest, and Sanctions movement on college campuses; the appearance of

Israel-bashing letters to the editor and op-ed pieces in the media; and

the involvement of some Christian denominations in campaigns to divest

funds from firms doing business with Israel. The Jewish Community

Relations Council has had some success in sponsoring events for “opinion

leaders” in the general Springfield community and in promoting dialogue

with local churches, whose pastors and congregants have been largely

sympathetic to the Jewish community’s concerns.

For

those who have moved here from larger Jewish communities, Springfield

lacks many of the institutions and amenities of urban Jewish life.

Springfield, with 900-plus Jews, is a small Jewish community in

comparison to Chicago (250,000) or St. Louis (55,000). The city no

longer has a kosher deli, meat market or bakery. Neither does it have a

Jewish community center, nursery school or “day school” (a private

Jewish school combining secular and religious instruction under the same

roof, akin to a Catholic or Lutheran parochial school). Springfield’s

Jewish Federation and temples make up for the lack of Jewish

infrastructure by being a warm, welcoming and caring community.

The

Internet makes it possible to order Jewish books and read Jewish

periodicals online. Jewish camping (notably, Olin Sang Ruby Institute in

Oconomowoc, Wisconsin, and Camp Ben Frankel in Carbondale) have made it

possible for young people from Springfield to meet their Jewish peers

from other cities and to learn about Judaism in an informal and fun

setting. Many of our Jewish young people have taken advantage of the

“Birthright” program, offering free of cost educational trips to Israel

for the 18- to 26-year-olds.

Recent

developments Over the last decade, demographic factors have not been

favorable for the Springfield Jewish community. There are few remaining

locally owned Jewish businesses. The number of state of Illinois

employees who identify as Jewish in Springfield has declined. Neither

UIS nor SIU School of Medicine seem to have attracted the number of

Jewish faculty members in recent years that they did in the past. Both

temples have experienced declining membership rolls. Our young people by

and large do not return to Springfield after completing their college

and professional education, and promoting synagogue or Federation

affiliation to those “millennials” who do reside here is a hard sell.

It

is difficult to predict the future. Springfield Jews are proud of what

their community has achieved over the past almost 160 years and of the

level of activity we maintain. Our leaders at the Temple and the

Federation are well aware of the challenges we face and will devote

their energies, their wisdom and their skill to assuring a Jewish future

in Springfield.

Rabbi

Barry Marks of Springfield has been the spiritual and community leader

of Temple Israel for more than 40 years. He recently was a guest speaker

at a University of Illinois Springfield Alumni SAGE Society luncheon,

co-sponsored by the Illinois State Historical Society, where he explored

the topic “Holocaust Remembrance and the rise of Anti- Semitism in

Europe and the United States.”