Take me out to the ballgame

A brief history of Springfield baseball

SPORTS | Bruce Rushton

In almost every large town in the state, base ball clubs have been organized this spring. We notice in our exchanges, not only in this state but all states, that this game is more popular than ever. It certainly affords amusement and healthful recreation, and is peculiarly adapted to the physical wants of young men whose occupations seem to weaken and encrust the system. We vote for a club in this city, and not only one club, but several. Let our young men take hold of the matter and put it through.

– Illinois State Journal, May 10, 1866

It began in Springfield one year after the end of the Civil War.

Andrew Johnson was president and widely despised. Copperheads were considered in political discussions. Newspapers kept careful track of cholera, reporting regularly on how many had been stricken and how many had died in towns between St. Louis and Chicago. And Springfield, back in the spring of 1866, was on the cusp of falling for the national pastime.

It was the start of baseball in a town that has never had a major league franchise and has only intermittently enjoyed minor league teams with paid players. Springfield has lured players and pillars of the game both legendary and forgotten. Some stayed for a season, some for a day, some for a lifetime.

Satchel Paige. Josh Johnson. Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Ray Chapman. Joe DiMiaggio. Mickey Mantle. A. Ray Smith. Seth Brock. The San Diego Chicken.

Springfield was behind the times at the very beginning. Jacksonville, Illinois College and Decatur already had clubs when the Illinois State Journal in the spring of 1866 urged that a team, or better yet teams, be organized in the capital city. The sport was new enough to locals that the newspaper published the rules first written down two decades previously in New York.

“It is very easy to learn, and is capital sport, barring the cannon ball which the players are expected to catch in rather soft hands,” the newspaper intoned. “Ladies will enjoy the game, and of course are expected as admiring spectators.”

Five days later, on May 15, 1866, 30 men gathered at the Statehouse to organize the city’s first club, dubbed the Capitals. The next day, the Olympics were born at another meeting. By the end of the month, there was a third club, the Eagles. Before season’s end, at least a half-dozen clubs called Springfield home. The Capitals, considered the best, met regularly at the Supreme Court room in the state Capitol.

The Capitals and Olympics, considered the city’s best, met for the first time on July 28, 1866, playing in heat so withering that two players had to leave the field at Sixth and Monroe streets.

“Several ladies were present, who seemed to enjoy the sport exceedingly, and, like ladies generally, exhibited their partisanship in small screams of approbation (generally at the wrong time),” reported the Journal, which consistently noted the presence of women at games. Historians say that women were encouraged to show up at early baseball games to reduce drinking, gambling and assorted forms of lout-ish behavior by men.

The Capitals won, 67-41, and the score wasn’t an anomaly. Box scores from the time show that one team would score as many as 90 runs in a game, with neither side hitting more than one or two home runs.

The reasons for football, even basketball, scores in baseball’s early days are numerous and myriad, says Thomas Shieber, senior curator at the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York. For one thing, no one wore gloves. Crude fields invited bad hops. And rules were different. If batted balls first bounced in fair territory, they were considered fair, and so-called fair-foul hitters flourished by hitting balls that touched ground just in front of home plate, then zinged to one side or the other.

“It can go quite a long way – if there was a dugout there, it would be going into the dugout,” Shieber says. The field of play was thus effectively enlarged, with first and third basemen forced to play close to foul lines, which opened gaps elsewhere.

A tournament scheduled for

Bloomington on Sept. 11, 1866, featured a $50 prize and was supposed to

draw clubs from as far away as Detroit and St. Louis, according to an Illinois State Register story published two months prior to the contest.

“Subpoenas

in the shape of invitations will be issued to all the organized clubs,

and we give our base ballers of Springfield timely notice to gird up

their loins and prepare for the fray,” the Register announced.

“To fat players, who wish to do the running part, we give seasonable

advice to lose flesh at once, to which we would suggest a mile or two of

running at any time from twelve to two in the day and total abstinence

from lager.”

The

Capitals, due to play in Bloomington, merged with the Olympics seven

days before the tournament began, with the new club being called the

Capitals. Whether a team from Springfield showed up isn’t clear. The

contest unfolded over several days in oft-rainy weather, with no

Springfield team mentioned in stories published in Springfield

newspapers or the Bloomington Pantagraph. Inclement weather curbed attendance, the Pantagraph reported, but an all-star game attracted 600 or so spectators.

That Springfield had fallen in love with baseball was obvious to outsiders.

“There is no cholera there, but they have a complaint not set down in books, which is raging fearfully,” reported the Pike County Democrat in

describing a visitor’s trip to the capital city in the fall of 1866.

“We suppose it may be called ‘base ball on the brain.’ In business hours

on the street, go where you will, and you hear the professional terms

of the game flying in all directions.”

Pioneers and gimmicks Early baseball in Springfield wasn’t exclusively a white man’s game.

The Journal in

1869 reported that a “colored” team called the Dexters had played a

game with an unstated opponent, the outcome of which the paper failed to

report. The paper covered the contest by word of mouth.

“We understand that the game was wellcontested and that considerable money changed hands on the result,” the paper reported.

A

game on Sept. 11, 1875, between two female teams attracted considerably

more attention, with an estimated 200 spectators paying to watch the

Brunettes play the Blondes at a field on North Seventh Street. The

players were paid for their efforts. The game is believed to be the

first between two women’s teams with paid players and admission charged.

“It

is a big deal that Springfield was the first,” says Debra Shattuck of

Rapid City, S.D., who has written a book on women’s baseball scheduled

to be published next year. “The fact that your Springfield women’s team

was drawing a few hundred is actually quite respectable, in terms of the

number of people who were coming to watch them.”

Conceived

as a novelty, the Blondes and Brunettes were the brainchild of Frank

Myers, a local merchant and auctioneer, Thomas Halligan, an auctioneer

who worked in Myers’ showroom, and Seth Brock, a justice of the peace.

They ensured no free shows by surrounding the field with a

nine-foot-high canvas screen. The base paths were 50 feet long instead

of the regulation 90 feet and bats and balls were lighter than those

used by men.

The

Blondes prevailed, 42-38, over the opposing team, which had just eight

players. The six-inning contest that lasted two hours was reviewed

favorably by both the Journal and the Register, which reported that the players wore “jaunty hats” and pants that ended somewhere between knee and ankle.

“Everything…was

done decently and in order, and there was nothing, save, perhaps, the

exhibition of female anatomy, to which exception could be taken, and

even that is frequently discounted in first-class theaters,” the Register wrote.

Both the Register and Journal printed box scores, but not a single player’s name appears in 1875 city directories.

“They

almost always used stage names,” Shattuck says. “It wasn’t necessarily

shame. It had more to do with creating mystery. They would always be

listed so that men in the audience could hope that they would at least

have a chance.”

From

Springfield, the Blondes and Brunettes went to Decatur, then to St.

Louis and then to the East Coast. The media were bemused when a game in

Brooklyn was scheduled.

“What

a crowd there will be to see the match, and with such a susceptible set

of fellows as our Brooklyn boys are, what a number of catches the fair

ball tossers will make, especially the brunettes, who are famous for

that sort of thing,” the Brooklyn Daily Eagle observed, according to a book by James L. Terry.

The

Blondes and Brunettes disbanded about three months after playing their

first game, Shattuck says. But they still proved an inspiration.

In

1883, another pair of touring women’s teams, also called the Blondes

and Brunettes, formed in Philadelphia and played before crowds as large

as 1,500. Early women’s games, Shattuck says, were more Harlem

Globetrotters than New York Yankees, with staged plays and more

theatrics than athleticism. But bona fide women’s teams with players

dubbed Bloomer Girls crisscrossed the nation in search of serious

competition by the century’s end, and men in wigs typically played as

pitchers, shortstops and catchers, Shattuck says. One example is Smoky

Joe Wood, a Hall of Fame pitcher and outfielder who disguised himself as

a Bloomer Girl to play while still a teenager.

From

spitballs to softball In the years before World War I, Springfield

longed for a minor league team with paid players who had a shot at the

big leagues. A franchise was secured in 1903, when backers purchased

the Joliet Standards for $300 and moved the club to Springfield, where

the team was renamed the Foot Trackers. A 1,200-seat grandstand was

hastily added to an 800-seat ballpark at 11 th Street and Black Avenue.

It

marked the start of an on-again-offagain love affair with the minor

leagues that played out over the better part of the next 100 years.

Prior to Springfield entering the Illinois- Indiana-Iowa (Three-I)

League in 1903, just four seasons of minor league ball had been played

in Springfield since 1883, with no team lasting more than a season.

The

local press wasn’t afraid to criticize the Foot Trackers. Soon after

Springfield landed the team (which would, over the years, be known as

the Hustlers, Watch Makers, Senators, Tractors and Browns), the State Journal warned that attendance had been dwindling due to poor play.

“Several

ugly reports are getting about concerning some of the local players,”

the paper intoned after an ugly 8-3 loss to Decatur on Aug. 4, 1903. “If

they are true, and there is good reason to believe they are, baseball

might as well come to an end in Springfield. A baseball player cannot

keep up the saloons at the same time he is trying to keep up his batting

and fielding averages. … Any amount of kicking on the umpire’s

decisions will not atone for a night of carousal.”

The team survived and sometimes thrived.

With

the help of Ray Chapman, who played every position except pitcher and

catcher, the Springfield Senators finished first in the 1910 season with

a record of 88-48. Ten years later, Chapman, then a shortstop for the

Cleveland Indians, was having one of his best seasons ever when he was

struck on the head by a pitch and killed. The 1920 tragedy prompted a

ban on spitballs.

Springfield’s

Three-I team folded in 1915, but lower-tier minor league teams with

such names as the Reapers, Midgets and Merchants helped keep baseball

alive. The city rejoined the Three-I with a new franchise when the

league expanded in 1925. The new team needed a new stadium, and so

construction on Reservoir Park, now called Robin Roberts Stadium, began

in March of 1925. Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the infamously taciturn first

commissioner of baseball, threw out the first pitch in the new

ballfield after a luncheon in which he blasted lackluster efforts to

help disabled veterans.

“It is criminal, and the people should be indicted for it,” the former judge declared.

The

Springfield club folded in 1932 along with the rest of the league, but

the Three-I came back a few years later, and the capital city had a club

in the league until 1950, when the Springfield Browns moved to Cedar

Rapids. The Giants, a D league team, replaced the Browns but played just

one season. J.R. Fitzpatrick, the Giants’ owner, sold the uniforms to a

team in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan.

“We

did not have to look at the financial statement to know that as a

baseball city in the minor leagues Springfield was a flop,” Fitzpatrick

wrote in an article published in a book of Illinois history. “With radio

and television bringing in the top stars of the entertainment field, no

local or less-than-topflight entertainment could compete.”

Regardless

of the minor leagues, amateur baseball in Springfield thrived during

the first half of the 20 th century, with businesses and fraternal

organizations sponsoring teams whose performances were chronicled in box

scores published in daily newspapers.

The

municipal league games were worth watching, says John Richard “Ducky”

Schofield, who was born in the capital city in 1935 and broke into the

major leagues with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1953. Some amateur

players, Schofield recalls, had minor league experience and were better

than some paid players they competed against.

“A

lot of guys couldn’t make it,” recalls Schofield, whose son Dick played

in the majors for 13 years; his grandson, Jayson Werth, plays for the

Washington Nationals. “They were married, they signed and went away.

They couldn’t make it on $75 a month, so they’d come home and make three

times that much working in a coal mine or something. It was good

baseball. They had some good teams.”

Softball

was at least as popular as baseball, Schofield says, with games at Iles

Park drawing as many as 3,000 spectators during the 1940s.

“Softball at Iles Park was probably one of the biggest attractions in Springfield,” Schofield says.

Not

so women’s baseball. One year after building a stadium on Third Street,

not far from Stanford Avenue, Fitzpatrick in 1948 established the

Springfield Sallies. Schofield’s father had played with the Sallies’

manager in the minor leagues, and so Schofield pitched batting practice

to the women’s team.

“I was in the eighth grade,” Schofield recalls.

“They were pretty good players, some of them.”

The

team’s record, however, suggested otherwise. After one losing season in

Springfield, the team became barnstormers. The team folded in 1951.

AAA

comes and goes In 1977, the ballpark at Lanphier High School was

renamed Robin Roberts Stadium in honor of the pitcher from Lanphier who

had entered the Hall of Fame the previous year. One year later, the

highest level of baseball ever played in the capital city got its start

when A. Ray Smith moved his AAA team from the New Orleans Superdome to

Robin Roberts and began play as the Springfield Redbirds, top farm club

for the St. Louis Cardinals.

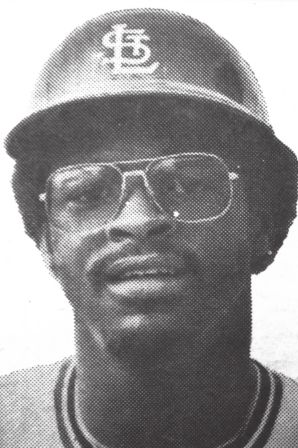

Smith

hired Satchel Paige, the legendary Negro League pitcher, as a vice

president whose job was largely watching games in the grandstands with

fans, sometimes alongside Josh Johnson, his former catcher in the Negro

Leagues who had moved to Springfield in the 1960s and taken jobs with

the state boards of education and elections. Smith also brought such

legends as Bob Feller, Warren Spahn, Billy Martin, Mickey Mantle and Joe

DiMaggio to town for banquets.

“He

liked to big-dog it, so to speak,” recalls Paul O’Shea, who recently

retired as planning and design coordinator for the city of Springfield

and served on a baseball advisory committee when the Redbirds landed

here.

Leon

“Bull” Durham, a first baseman and outfielder who lasted for a decade

in the majors, played here, as did Aurelio Lopez, a pitcher who had

starred in a Mexican league before coming to America. He was known as

Senor Smoke while helping the Detroit Tigers to a World Series title in

1984. Springfield called him Taco Gringo during his half-season here in

1978.

Smith threatened

to move the Redbirds after just one season, saying that he was upset by

shabby treatment from the media. After four seasons, the team went to

Louisville. A group of local would-be buyers that included O’Shea had a

preliminary agreement to buy the team for $600,000. Then O’Shea heard

that Smith was still talking to boosters in Louisville.

“We

just backed off after that,” O’Shea recalls. The Cardinals provided

Springfield with an A league franchise in the Midwest League after the

Redbirds departed, and several future stars, including Ray Lankford,

Todd Zeile and Vince Coleman, passed through the capital city.

“It

was a nice place to play,” recalls Mike Pitttman, a pitcher who stayed

in Springfield and became a developer after his career was cut short by a

rotator cuff injury. “It was one of the best cities that I played in

back in the Midwest League.”

Pittman

recalls playing before a crowd of 6,000 that came not so much to see

baseball as to watch the antics of the San Diego Chicken, a mascot that

became a national sensation during the 1980s. Dwindling attendance and

dissatisfaction over the condition of Robin Roberts Stadium prompted the

St. Louis Cardinals to sell the Springfield franchise after the 1993

season. The Springfield Sultans, a Class A club in the Padres and then

Royals farm system, played for two years, followed by a few independent

minor league teams. The Springfield Sliders, stocked with collegiate

players, now call Springfield home.

Whether it’s the Sliders, the Redbirds or the Sultans, baseball teams in Springfield have always been appreciated, O’Shea says.

“For the most part, they all served their purpose,” O’Shea says. “It’s always a fun time at the ballpark.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].