In Illinois prisons, getting sick can be a death sentence

When Rubin Watts arrived at the Dixon Correctional Center infirmary in 2007, his legs and feet were red and swollen, with stinking open wounds that were oozing pus and a bloody discharge. He had a skin infection called cellulitis and a history of mental illness.

Shortly before Watts’ arrival in the infirmary, he’d been seen naked in his cell, obsessively washing the floor and trying to eat his jumpsuit and a blanket, according to a lawsuit filed by his family. Once in the infirmary, he chanted, screamed, called nurses “mommy” and “daddy” and urinated on himself, according to the lawsuit and the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, which licenses and disciplines doctors.

A doctor noted that Watts appeared in no distress the day after he arrived at the infirmary, even though the staff that same day wrote that he was yelling and restless and repeatedly pulling on IV tubes, according to IDFPR records. Three days after Watts was admitted to the infirmary, a doctor concluded that muscle damage likely had occurred from the infection. He wasn’t responding to simple commands. His legs became cool to the touch. His mind wasn’t any better.

“Sitting on the floor, drinking out of the toilet,” the staff observed after Watts had spent nine days in the infirmary, according to IDFPR records. “Ulcers healing well and dry,” a physician observed that same day and also noted that Watts’ body temperature had dropped – the staff recorded it at 93.2 degrees.

In the next few days, Watts smeared feces on his legs, through his hair and all over his infirmary room, according to IDFPR records and the lawsuit filed by his next of kin. But there were signs of progress, according to staff notes. His sores had crusted over. On Dec. 10, 2007, the staff noted that his vital signs were stable. “(C)ellulitis resolving well with decreased open areas of skin,” the staff observed in notes.

Watts died the next day. Watts succumbed to sepsis caused by cellulitis, with bacteria found in his heart, lungs and kidneys and dead tissue in his pelvic wall and loin muscles. No one had summoned an infectious disease specialist while Watts was alive, nor was his prescription for an antibiotic changed when he didn’t improve. Even as Watts chanted and smeared feces, a psychiatrist reduced a prescription for Risperdal, a drug used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. He wasn’t taken to a hospital, even though a nurse had filled out a transfer form four days before he died.

The state paid $50,000 to settle a lawsuit brought by Watts’ family. Wexford Health Sources, the company that holds the contract to provide health care in Illinois prisons, also settled a lawsuit, but how much the company paid isn’t a matter of public record.

Dr. Rajender S. Dahiya, a Wexford employee, was a defendant in court and a respondent in a complaint fielded by IDFPR, which reprimanded the physician and issued Dahiya a $1,000 fine. He remains a physician in good standing in the state of Illinois.

Cockroaches, toothaches

The Watts case isn’t unusual in the Illinois Department of Corrections, according to lawsuits that have resulted in verdicts and settlements paid to inmates or their next of kin during the past decade.

Lawsuits alleging horrific care are buttressed by a recent report from a courtappointed panel of experts that was led by the former medical director for the state prison system (“Experts blast prison health care,” IT, May 28, 2015).

Health care in Illinois prisons is so poor that it constitutes cruel and

unusual punishment, the panel found. The findings are part of a

class-action lawsuit filed by inmates who demand improvement that hasn’t

resulted from more than 1,300 lawsuits against the state in the past 10

years and nearly 120 settlements and verdicts paid over that same

period of time.

In

a written statement emailed in response to an interview request, Nicole

Wilson, corrections spokeswoman, said that the state is working on

improvements to health care in prisons. The state has already increased

staffing in some areas, Wilson wrote, and is working on improvements in

record keeping and as well as creating a “robust quality assurance

program.” Wilson wrote that the state hopes to gain accreditation at

many prison facilities from the National Commission on Correctional

Health Care (NCCHC), a nonprofit body established to improve health care

in correctional facilities.

“The

IDOC has always been and continues to be open to suggestions for

improvements and willing to take the necessary actions when

appropriate,” Wilson wrote. “We contend that leadership and clinicians

within our healthcare units are qualified and properly credentialed,

that chronic illnesses are appropriately treated and that the IDOC is

providing constitutionally adequate care.”

Accreditation

by the NCCHC doesn’t guarantee that prison health care will pass

constitutional muster, according to the report from the expert panel

that was led by Dr. Ronald Shansky, former IDOC medical director who

served on the NCCHC board for a decade. NCCHC accreditation, while

valuable, focuses mainly on administrative issues, according to the

expert panel, and Illinois needs to address clinical care.

On the whole, substandard treatment hasn’t cost taxpayers very much.

Take

out a $12 million verdict awarded in 2013 and the state has paid less

than $704,000 over the past decade in 116 cases, most of which were

settled out of court. It works out to less than $6,100 per case. It’s

not clear how much Wexford has paid. But settlement amounts don’t begin

to indicate horrors both small and large.

Consider

the case of Darnell Cooper, who awoke at Stateville Correctional Center

in Joliet to find cockroaches biting his face in 2012. He waited more

than a week before he got ointment to treat the bites. When he asked

Marcus Hardy, then the warden, to have his cell sprayed for roaches, the

warden, according to a lawsuit filed by Cooper, replied, “You’re asking

a lot, aren’t you?” The cell was never sprayed, according to the

lawsuit.

Cooper, who

also alleged that he contracted a painful toe fungus due to filthy

conditions that included sewage in a shower, settled his lawsuit last

year for $12,000. Hardy was promoted and now oversees adult prisons in

central Illinois.

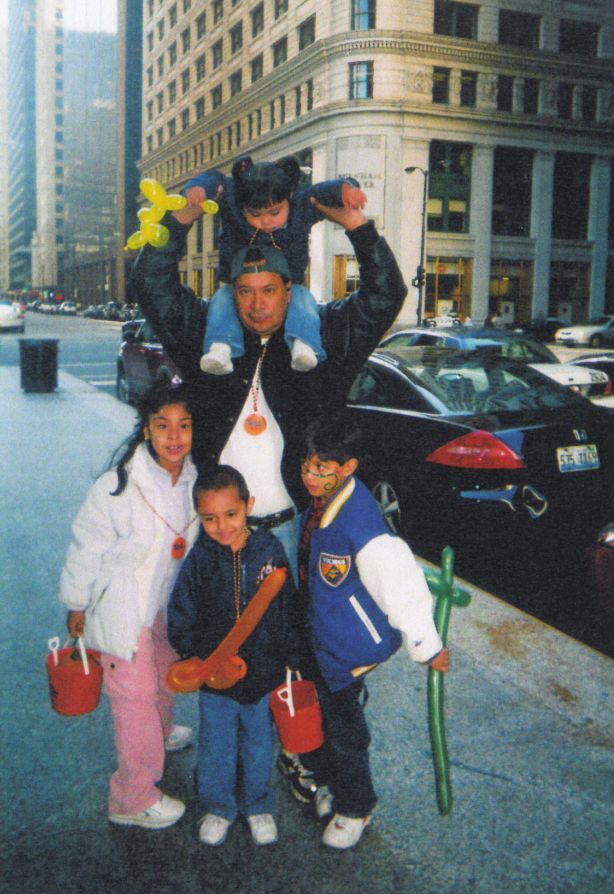

Francisco

Gonzalez, who is serving a 45-year sentence for methamphetamine

convictions, waited months for treatment at Stateville in 2010 after the

pain started and a dentist found a hole in a tooth. He filed grievances

and told Hardy, the warden, that his tooth hurt.

While

Gonzalez waited for dental care, another tooth broke and infection set

in. He was given Tylenol and an antibiotic. Three months later, and nine

months after Gonzalez first complained of pain, a dentist extracted the

broken tooth and the one with a hole. By then, Gonzalez needed a

filling in a third tooth. He got one seven months later. The state

settled the case for $7,000.

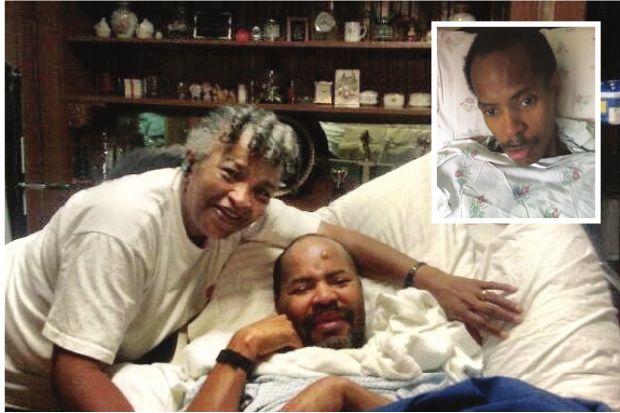

‘Money is not going to replace a human life’ The case of Montell Johnson is as absurd as it is sad.

Convicted of murder for a Macon County killing, Johnson’s death sentence was converted to a 40-year

term in 2003, when former Gov. George Ryan commuted all death sentences

in the state. By then, Johnson had developed multiple sclerosis. By

2007, he was bedridden and unable to speak. His mother, Gloria

Johnson-Ester, communicated with her son by having him close his eyes

while she recited the alphabet. When she got to the appropriate letter,

he would open his eyes and so, slowly, would spell out what he wanted to

say.

Johnson

reached an advanced stage of dementia at Dixon Correctional Center and

developed bedsores down to the bone – he told his mother that the sores

had become infested with maggots, according to a lawsuit brought by his

mother, who had power of attorney to make medical decisions for her son.

“The

doctor wrote that he had recommended a feeding tube, but Montell

refused it,” recalls Harold Hirshman, attorney for Johnson-Ester. “Since

he couldn’t feed himself, he nearly starved to death. He got down to 70

pounds or less.”

With

his condition deteriorating, Johnson was sent to the University of

Illinois Medical Center in Chicago. U.S. District Court Judge Suzanne B.

Conlon in 2007 barred the Department of Corrections from returning him

to prison from the hospital, saying that the plaintiffs had a

substantial chance of prevailing, and without adequate medical

treatment, Johnson’s life was in peril.

After

the hospital told the court that Johnson was doing better, he was sent

to a long-term care facility and, eventually, to Sheridan Correctional

Center. Former Gov. Rod Blagojevich saw the folly of incarcerating an

invalid and so granted clemency in the fall of 2008. But Johnson wasn’t

freed.

California,

where Johnson had been serving a life sentence for murder before he was

extradited to Illinois in the 1990s, wanted Johnson back so that he

could spend the rest of his life in prison.

“He

was bedridden,” recalls Alan Mills, executive director of the Uptown

People’s Law Center in Chicago that is representing inmates in the

class-action lawsuit against the state. “He couldn’t talk. He couldn’t

move. He kind of did the blink-and-grunt thing, which only mom could

interpret because she’s mom. There was no reason for this guy to be in

prison.”

At the time,

California was under pressure to reduce its prison population. In 2009, a

federal court ordered the state to reduce the number of inmates by 27

percent within two years as a means of improving poor health care in

California prisons that constituted cruel and unusual punishment.

“It

was absurd,” Hirshman says. “Since California can’t take care of the

sick people it already has, the idea of them taking an incredibly sick

person back was ridiculous.”

Johnson-Ester sued California and a deal was cut. In exchange for Johnson’s promise never to return to California, California authorities

agreed that they would not seek his return to prison. He was released

in 2011 and now lives with his mother in Chicago.

Nine

months after her son was freed, Johnson-Ester settled her case against

the state of Illinois alleging substandard medical care for $75,000. It

was the largest amount the state has paid in the past decade to settle a

lawsuit alleging poor medical care in state prisons.

“Everybody

tells me I should have held out (for more money), but I preferred to

have my child,” Johnson-Ester says. “I was scared that he wasn’t going

to make it. The money won’t help me at all. Money is not going to

replace a human life.”

Hirshman

has since settled another lawsuit, he says for six figures, which would

make the Chicago lawyer one of the state’s most successful litigators

in cases alleging poor medical care in prisons. Settlement agreements

are public records, but state prison officials declined to provide a

copy, saying that the settlement has not been “finalized.” The case

involved William Stellwagen, who was serving a six-year sentence for

home invasion.

Stellwagen,

a drug abuser and alcoholic for most of his life, was dying of liver

disease when his wife sued the state in the fall of 2013, asking that a

judge order him freed so that her husband could spend his final days

with her in California. She told the court that her insurance would

cover the cost of hospice care. But prison officials, including Dr.

Louis Shicker, medical director for the Illinois Department of

Corrections, assured the court that IDOC would provide hospice care as

needed, and Stellwagen remained in prison.

Stellwagen

died on Feb. 11, 2014, but litigation continued. Contrary to Shicker’s

promise to the court, Stellwagen had not received hospice care in his

final days, according to court records. He remained in the Dixon

Correctional Center infirmary as his skin yellowed. He became forgetful,

confused, subject to hallucinations and prone to falling. “I feel the

worst I’ve ever felt,” he told a nurse two weeks before he died.

After

not hearing from her husband in five days and not having calls returned

by prison staff and doctors, Stellwagen’s wife flew to Illinois from

California and found her husband incoherent in a Dixon infirmary bed. He

had fallen at least once, records show, and it appeared that he might

have suffered a broken nose. An IV port in his arm led to nothing. His

blood pressure was so low due to dehydration that an attempt to

administer pain medication via an IV drip failed According to the

lawsuit, a doctor injected a painkiller in Stellwagen’s hip at the

request of his wife.

As

Stellwagen’s wife sat with the dying man, the room grew cold, and he

was covered with just one thin blanket. According to the lawsuit, his

wife had to beg the staff for a second blanket. Stellwagen died hours

later.

‘Everybody knows how bad it is’

Hirshman

and other lawyers who have sued the state and Wexford Health Sources, a

Pittsburgh-based company that holds the contract to provide health care

in state prisons, say there are several barriers to bringing successful

lawsuits. For one thing, Hirshman says, finding good cases can be

difficult. For another, neither the state nor Wexford gives up easily.

“The

way the system works, the state has Wexford shielding it from most

liability and Wexford is tenacious about saying ‘Nobody did anything

wrong,’ and there are insufficient lawyers who are willing to take on

these kinds of clients,” Hirshman says.

Michael

Kanovitz, a Chicago attorney who in 2013 won a $12 million verdict

against the state – the most, by far, a plaintiff has won from the state

in the past 10 years – says that lawyers share the blame for low

payouts. Too often, he says, attorneys for inmates aren’t preparing well

enough to go to trial.

“There

is an assumption in the…bar that these cases aren’t particularly

meaningful – no one is going to listen to a prisoner,” Kanovitz says.

“That’s a prejudice we’re trying to disprove. And we certainly disproved

it in Ray Fox’s case.”

Fox,

a nonviolent drug offender incarcerated at Stateville, suffered a brain

aneurysm in 2007 after seizures that began when he was denied his

prescription for an anti-seizure medication. In addition to the $12

million verdict against the state, a judge awarded Fox’s legal team $1.5

million in fees and costs. Wexford settled for $3 million. Fox survived

but has the mental capacity of a five-year-old. The state went to trial

after settlement talks broke down.

“We

knew that Ray’s injuries were very serious,” Kanovitz says. “We treated

them not the way that the system often treats prisoner injuries. Our

settlement demands were high only because that’s what they should be for

any human being.”

That health care in Illinois prisons needs dramatic improvement is no secret, Kanovitz says.

“Everybody

– everybody – in the system knows how bad it is,” Kanovitz says. “The

judges know how bad it is. The prison officials know how bad it is. But

the private attorney bar has not stepped forward to take them to task

the way they should be.”

Mills,

the lawyer who has sued the state alleging that health care in Illinois

prisons violates the constitutional rights of inmates, says that low

settlements discourage lawyers from taking cases. Even a $12 million

verdict isn’t much, he says, considering that Wexford’s contract with

the state is worth $1.5 billion over 10 years.

“On

a $1.5 billion contract, a $12 million verdict is a rounding error, and

there’s only one of those,” Mills says. “The courts are not awarding

big-money damages – there’s no political will. … I know that Wexford has

people who are loss managers, and they know perfectly well how much

they’re going to have to pay based on the quality of care they provide.

They’re a for profit company. That’s their obligation: to their

stockholders.”

Kanovitz says that privatizing prison health care is a bad idea.

“The

economic incentives of the entities that are entrusted is to give as

little care as possible,” Kanovitz said. “They’re in an industry where

they don’t think they will be scrutinized. Even if the worst-case

scenario happens, juries won’t care that much. So they are emboldened.”

Wexford did not respond to a request for comment.

Mills says that he’s lost hope that individual lawsuits will force reform.

“That’s

why we switched and are doing the class-action case,” Mills said. “The

damage cases are never-ending, and they’re not going to change the

system.”

‘Without medicine I will never be cured’

About

recover (sic), today I went to the doctor and now that I said it hurts

this and that, the doctor doesn’t let me speak, and I told the doctor:

With all respect, I come here because I feel bad, not to yell at me, I’m

not a child, I am an adult 53 years old. And the doctor told me “I did

the tests that had to be done and you have nothing.” I said “I only know

how I feel and I need care.” And the doctor said “What you need is a

psychiatrist.”

For

months, Alfonso Franco in letters to relatives chronicled what it’s

like to die of cancer in prison. How difficulty with defecation is

dismissed as simple constipation and treated with milk of magnesia and

advice to get more exercise. How the skin turns yellow and pounds melt

from your body and blood appears in your urine and stool. How nausea

during a visit with a prison doctor results in an x-ray and an opinion

that it’s hemorrhoids. How the appetite disappears and the pain

increases to the point of becoming unbearable, but no painkillers are

prescribed.

“As I tell

you, I don’t think this is anything serious, but without medicine I

will never be cured,” Franco wrote in a letter to his wife that was

translated from Spanish and provided to Illinois Times by a lawyer for Franco’s family.

Franco’s

complaints began with constipation in the fall of 2010. He had already

started to lose weight. In the summer of 2012, he was hospitalized after

Dr. Rosalina Gonzales, a Wexford employee, noticed a mass on his liver.

By then, he was in diapers and having dozens of bowel movements each

day. He had lost more than 50 pounds.

Doctors

outside the prison determined that Franco was in the final stages of

colon cancer that had spread to his liver and lungs. It was, by then, a

hopeless case. Franco was sent back to prison from the hospital. He died

at the age of 53, one month after his cancer diagnosis and nearly two

years after he complained of constipation coupled with weight loss,

classic symptoms of colon cancer.

Timothy

Shay, attorney for Franco’s family, says that Franco, who was serving

time for cocaine possession, would be alive today if he had received a

colonoscopy when he first complained of constipation.

“This

guy was going to the bathroom 50 times a day and nobody had a eureka

moment that he needed to go to the Taylorville hospital,” Shay said.

Gonzales’

license to practice medicine in Illinois expired last year. At last

report, Shay says, she was in the Philippines and unavailable for a

deposition.

There is

no shortage of job opportunities at Wexford. According to the company’s

website, there are 60 openings at prisons within 50 miles of

Springfield, including more than 40 positions at Logan Correctional

Center in Lincoln. On its website, the company tells would-be employees

that the company pays for malpractice insurance and there is a “steady

income with no need to look for new patients.”

“At

Wexford Health, our philosophy is that health care should not be a

luxury for anyone,” the company says in its online pitch to applicants.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].