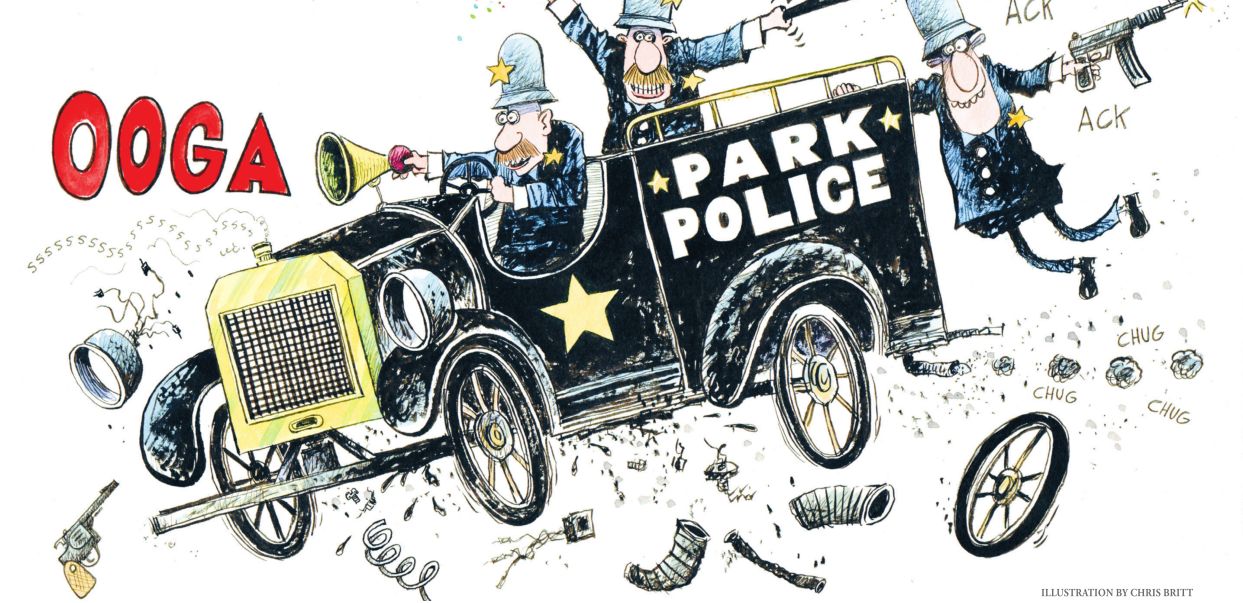

Law enFARCEment

Park cops protect, serve and screw up

POLICE | Bruce Rushton

The Springfield Park District police department doesn’t sound like a tight ship or a fun place to work. Consider a memo titled “Rumors” that former Capt. Jonathan Davis wrote to his officers in January 2014.

“Recently, it has been brought to my attention that there are many rumors floating around the department about me,” Davis, the department’s de facto chief, began.

The captain went on to say that he wasn’t mad at anyone. Sure, I keep my office door closed, but I’m a busy guy – just knock and I’m happy to talk. Don’t read anything into the fact that I ripped my name tag off my door, and don’t jump to conclusions just because I’ve been cleaning out my office. And stop gossiping and spreading rumors.

“I have not hidden the fact that like most of…you I’m seeking other employment,” the captain wrote. “I have not ‘checked out.’ I’m still here and completing the tasks assigned to me and completing my duties which include making sure you are carrying out your duties and tasks assigned to you.”

Hardly what one expects to hear from the commander of a police department that is, at least in theory, supposed to be run like a paramilitary organization, with the man at the top giving orders and underlings carrying them out. But that isn’t what has happened at the Springfield Park District police department, according to documents released under a state Freedom of Information Act request. And dysfunction could prove expensive for taxpayers as Davis, who says that he was forced to resign last month after being placed on paid leave, has signaled that he may sue the district.

Records show a series of disciplinary issues in the park police department, with Davis’ superiors not accepting his recommendations for punishing officers who violated department regulations and perhaps even laws. Ultimately, conflicts between Davis and his troops became so great that Jeff Wilday, the managing partner of the law firm that serves as the district’s counsel, recommended that the department’s three officers and Davis receive counseling so that they could learn to get along with each other.

Tension heightened and morale plummeted in the department as the number of officers was reduced in 2013 and 2014, records show. Officers griped about Davis, and park administrators often didn’t back the captain on disciplinary matters. And some officers who complained about Davis were hardly model cops themselves.

A “mediocre” officer

Prior to being hired in 2012, Officer Lawrence Bomke, the son of former state Sen. Larry Bomke, failed a written test designed to weed out unsuitable candidates, according to Davis, who declined an interview request but provided information via emails. Davis writes that he sent a letter to Bomke, informing him that he would not be hired. But the former captain says that when he returned from a vacation, he found that Bomke had been hired in his absence.

District files show that Bomke repeatedly screwed up as a probationary officer, prompting Davis to recommend that he be fired before probation expired, which would bring Bomke union protection that could make discipline difficult in the future.

During his first few months on the job, Bomke in a Facebook comment complained about working 13 days in a row and wrote that anyone who wasn’t behaving themselves would receive a citation unless they were “cute.”

In May of 2013, Bomke discharged his AR- 15, a military-style assault rifle, inside police headquarters in the early morning hours. His text message notifying Davis was the essence of understatement: “Call me whenever you get a chance.” He later told the captain that he believed that Davis was asleep at the time and he didn’t want to alarm or confuse him.

Bomke said that it was an accident, and there was no evidence to the contrary. But Davis, noting the prior Facebook incident, said that it was one mistake too many.

“Bomke’s overall performance has been mediocre at best,” Davis wrote in his report on the incident. “At this point, I believe that… Bomke has not demonstrated that he has the drive or discipline to continue on with his probationary status as demonstrated by his two issues of discipline which both show severe lapses in judgment.”

But Derek Harms, executive director of the park district, rejected Davis’ recommendation and suspended the officer

for three days after Bruce Stratton, an attorney for the district who

has contributed to former Sen. Bomke’s campaigns and other Republican

political causes, recommended a lesser sanction.

“We

believe that you have what it takes to become a credit to the

department and yourself,” Harms wrote in a letter to Bomke notifying the

officer of his suspension. “This suspension is not meant to punish, but

is intended to refocus your attention on certain aspects of your job

that we consider to be of the greatest importance.”

Twice

more before his probationary period expired, Bomke violated department

rules, once for putting a camera in a lost-and-found box instead of

logging it as evidence to be held for safekeeping and a month later for

doing the same thing with a wallet that contained currency and a debit

card. He received a verbal warning for the second incident but wasn’t

otherwise disciplined, files show.

In

the fall of 2014, after his probationary period ended, Bomke refused

the captain’s order to drive a fellow officer to an automobile repair

shop at the end of his shift to pick up a patrol car. Bomke said that he

was scheduled to close on a house purchase after work and didn’t want

to be late.

“Officer

Bomke appears to have taken on an attitude that he can choose what

orders he wishes to comply with and what orders he does not,” Davis

wrote in a report on the incident.

Davis gave Bomke a verbal reprimand, but it was removed from the officer’s personnel file after he filed a grievance.

Davis’ superiors didn’t back him, even while acknowledging that Bomke had disobeyed an order from the captain.

“We

questioned a bit if it (picking up the patrol car) really had to be

done at that exact time and why it couldn’t wait until the following

day,” Justin Reichert, an attorney for the district, wrote in an email

to Harms memorializing their conversation about the incident with Davis.

As

captain and the department’s de facto chief, Davis didn’t have

authority to discipline his officers for even minor issues. For

instance, when an off-duty officer used a department vehicle and wore

his department uniform while providing security at a store, contrary to

instructions, and Davis issued a verbal warning, Harms chided the

captain in an email, telling him to check with administrators before

taking such disciplinary measures.

In

January of 2014, Bomke succeeded in getting out of a shift after a

fellow officer called in sick. Bomke, who had been ordered by Davis to

work the shift, was the only officer available. But after calling

Reichert, Bomke went home after working just 90 minutes of the extra

shift.

Bomke told

Reichert that there was no activity in the parks due to snowy weather.

After checking with Harms, who gave his blessing, Reichert told Bomke

that he would not have to work the overtime shift. Only then did

Reichert notify the captain that Bomke wouldn’t be working the extra

shift. Davis brought up public safety – what if a sledding accident

occurred in a park? He also said that if the department’s staffing was

going to be further reduced, the district might just as well leave

policing in the parks to the Springfield Police Department. And he

complained about meddling.

“If

we’re going to make these kinds of decisions and respond to officers

calling us directly perhaps we should just run the department,” Reichert

wrote in an email to Harms and Davis memorializing what the captain had

said.

Two days later,

Bomke sent an email to Davis notifying him that a patrol car had an

exhaust leak that could be smelled inside and outside the car.

“Contact Justin Reichert and see what he advises,” the captain answered back. “Let me know.”

Repeated misbehavior

Bomke wasn’t the only park police officer who ran afoul of Davis.

Sgt.

Brian Crolly landed in trouble in August of 2013, when he stopped a

couple in Chatham, well outside his jurisdiction. He was driving his

personal vehicle at the time. The sergeant, who was wearing a vest

emblazoned with the word “police,” pulled alongside the couple after

tailgating them with his headlights on bright and yelled, “I’m a cop,

pull over!” The driver’s boyfriend said it appeared as if the sergeant

was having “a bad day,” according to district files.

Crolly

told the driver that he thought that she was intoxicated and summoned

Chatham officers, who released the couple after the sergeant left and a

portable breath test showed the woman had a blood-alcohol content of

.07-percent, below the legal limit.

It wasn’t the first time that Crolly had misbehaved.

Less

than two months before the Chatham traffic stop, Crolly admitted that

he had engraved a depiction of a penis on a cabinet at police offices

with “Bomke Loves” next to the picture. Crolly had also engraved obscene

images on a water bottle used by Bomke as well as equipment the officer

used to hold citations.

Crolly,

who sanded the engraving off the cabinet, told Davis that on a scale of

one to 10, the engravings were a five in terms of seriousness. Davis

thought otherwise. Intentional damage of government property can be

prosecuted as a felony, he noted in his report, and Crolly’s actions

violated the district’s policy on sexual harassment.

It

wasn’t the first time that Crolly had been involved in an incident that

could be construed as sexual harassment, Davis wrote in his report.

There had been a 2010 case, but Davis gave no details in his report and

the park district provided no detailed records pursuant to a request

from Illinois Times, which asked for documents pertaining to any

incidents of alleged misconduct by department employees dating back to

2008. The district, however, did turn over a handwritten note indicating

that Crolly in 2010 had told an employee “don’t be gay” when the

employee questioned the wisdom of locking up park bathrooms in the midst

of a lightning storm.

Davis wrote that Crolly wasn’t fit to be a supervisor after the sergeant admitted to defacing park property with vulgar images.

“Sgt.

Crolly’s actions in this incident range from criminal to immature,”

wrote Davis, who recommended that Crolly be demoted to patrol officer.

“Based upon his actions, I do not feel that Sgt. Crolly is any longer

capable of leading a young group of officers. I would also recommend

that the entire department undergo sexual harassment awareness training

as well as an ethical refresher course.”

But

Crolly wasn’t demoted, district files show, and Davis says that

employees didn’t undergo sexual harassment awareness or ethics training,

as the captain had recommended. Instead, Mark Bartolozzi, then director

of human resources, issued a 10-day suspension, with five of those days

held in abeyance and the district warning Crolly that he would be

suspended for those additional five days if he got in trouble again. Two

months later, the Chatham police chief was on the phone, complaining

about Crolly pulling over a vehicle outside his jurisdiction.

District files released to Illinois Times contain

no record of discipline for the Chatham incident; Davis says that

Crolly was counseled, the least-severe discipline possible, and did not

have to serve the five days of suspension that had been held in abeyance

for defacing park property two months earlier. Crolly’s rank was

eventually reduced to patrol officer, but not for disciplinary reasons.

Rather, it didn’t make sense to have a sergeant in a department with

just three officers and a captain, according to district files.

Problems

with Crolly continued in 2014, when he submitted three inaccurate time

cards within a span of less than two months indicating that he had

worked when he had actually taken sick or vacation days. He received

counseling, a verbal warning and a written warning.

Davis under fire

Davis

became the department’s de facto chief after Chief George Judd was

forced to resign in 2007 after forwarding an email to officers titled

“Proud To Be White.” Judd had also used the terms “nigger” and “sand

nigger” in conversation, according to Davis, who filed complaints.

Mike

Stratton, then the district’s executive director, gave no hint of

trouble in an email to employees announcing Judd’s departure. The chief,

Stratton wrote, wanted to spend more time with his son and

grandchildren.

“Chief will be missed as he set forth a great vision for the police department,” Stratton wrote.

Davis’

last year with the department was a rocky one. After Reichert and Harms

overruled the captain and told Bomke that he didn’t have to work an

extra shift as ordered in January 2014, tension between district

administrators and Davis mushroomed.

In

an email, Reichert told Davis that he was “clearly being difficult and

defiant” the day after the lawyer overruled the captain and told Bomke

that he didn’t have to work the extra shift. In a second email, Reichert

warned the captain to “discontinue difficult behaviors.”

“We

do not want to see you go down a negative path,” Reichert wrote.

“You’ve made it clear you don’t like our direction or our interference

with giving instructions to your officers. We will attempt to limit that

but believe better communication on your part with your officers and

management will help that.”

Strapped

for cash, the district had decided to reduce police staffing through

attrition, which didn’t sit well with Davis. Staffing was so thin that

when Davis went on vacation at the end of 2013, either Harms or

Bartolozzi, then the human resources director who has since left

district employment, filled in as head of the police department, even

though neither man has law enforcement experience.

By

the spring of 2014, the district had decided to remove the captain from

the department’s collective bargaining unit, a move that wasn’t opposed

by the union, according to district files. Reichert and Harms told

Davis it was a question of divided loyalty – he could not effectively

supervise officers while also being in their union. Davis saw it as the

first step toward termination.

“OK,

you’re trying to fire me,” the captain later told Wilday, the lawyer

who investigated alleged misconduct by Davis. “You don’t want me here,

you want me gone.”

Reichert

in the spring of 2014 told the captain to spend no more than 20 percent

of his time on patrol and the balance of his time on administrative

tasks, even though the department had just three officers. When he was

removed from the union last fall, Davis began wearing polo shirts

instead of his uniform and stopped logging in to the dispatch center

when he arrived at work. Officers complained that Davis always closed

his office door and locked it when he went to the bathroom. They also

complained that the captain rarely communicated with them except via

email and text messages.

Last

fall, as Davis’ separation from the union neared, Crolly in an email to

Harms accused the captain of not being available for calls and said

that Davis had signed time cards for a part-time ranger who wasn’t

working hours for which he was being paid.

“Captain

Davis has routinely let down his department and needs to be held

accountable for his actions,” wrote Crolly, who at the time was being

counseled and warned himself for submitting inaccurate timecards.

In

January, Davis was suspended for 10 days for signing the ranger’s

inaccurate timecards. The district figured it had paid the ranger $2,000

for hours that were never worked. Davis never returned to his job.

On

Jan. 9, shortly before Davis’ suspension began, Officer Nick Capranica

accused the captain of improper disposal of evidence by burning crack

pipes, clothing, marijuana and myriad other items without a court order.

That prompted the district to put Davis on paid leave pending an

investigation at the end of his 10-day suspension. While the captain was

off the job, officers on orders from Harms entered Davis’ office and

found four assault rifles, several pistols and thousands of rounds of

ammunition that were not secured in a gun safe.

Destruction

of evidence without a court order was the most serious matter, Wilday

concluded, but the park district had no policy on evidence disposal and

an Illinois State Police agent had told the lawyer

that Davis hadn’t committed a crime. Similarly, the park district had no

policy on securing weapons, Wilday found, but keeping weapons outside

gun safes didn’t seem prudent. In his report, Wilday wrote that the

district’s three officers thought that the captain should wear a

uniform, but Davis pointed out that park administrators frequently saw

him in polo shirts and never complained.

“Clearly, there are two sets of rules within the park district”

After Davis was placed

on leave, Bomke complained that the captain often arrived for work late

and left early, but Wilday couldn’t determine whether the accusation was

true. Harms and Reichert told Wilday that Davis had been uncooperative

and resisted their questions about the department; the captain countered

by complaining that administrators had undermined his authority by

allowing officers with concerns to go to Harms instead of through the

chain of command. Wilday also spoke with two representatives of the

National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, who shared

the captain’s criticism that his authority had been usurped.

Davis,

Wilday concluded, had fallen short of expectations. He should have worn

a uniform, logged in to the dispatch center when he reported for duty

and logged off when he left, and he should have been more accessible to

officers, the lawyer found. Harms should evaluate Davis’ performance in

writing every two months, Wilday recommended, and the captain should

draft performance evaluation forms for officers. The captain should also

write policies to govern the destruction of evidence and securing of

firearms. The district should attempt to expand Davis’ hours spent on

patrol. And both the captain and his officers should go to counseling

through the district’s employee assistance program to improve working

relationships.

“Assuming

that Capt. Davis accepts the fact that changes in his leadership style

and his communication skills are needed, he should be able to rebuild

his working relationship with his patrol officers in the short term,”

Wilday wrote in his May 5 report.

That

never happened. The day after Wilday issued his report, Davis resigned,

saying that he had been forced to quit. In an email to Illinois Times declining

an interview request, Davis wrote that Crolly and Bomke got wrist slaps

for their misdeeds, while he was placed on leave for more than three

months for baseless charges.

“Clearly,

there are two sets of rules within the park district,” Davis wrote. “I

will remain optimistic that these issues can be resolved through the

proper channels and if need be the legal system.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].