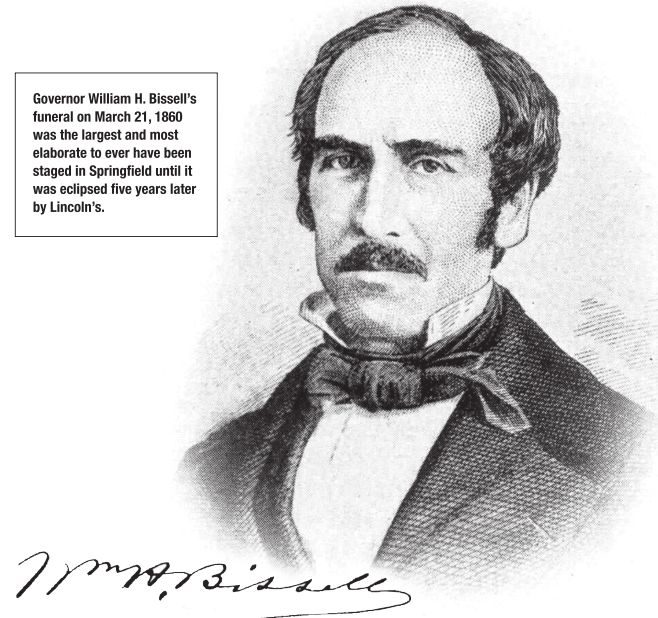

Blasts of cannon woke the citizens of Springfield at dawn on the day of the melancholy event. They fired every half hour until 11 o’clock, and every minute between 11 and noon. At 20 minutes past 10 the funeral procession began: first a dozen military companies, then the hearse, then more than two dozen civilian groups interspersed with bands of music playing a funeral dirge. The funeral of Gov. William H. Bissell that March of 1860 was the most elaborate outpouring of grief that Springfield had ever seen.

Bissell was the first sitting Illinois governor to die in office. A hero of the Mexican-American War, he rose to national prominence when he served in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1849-1855. Despite continued popularity, Bissell declined to run for re-election in 1854 due to failing health.

No one was exactly sure what Bissell was suffering from. Some believed that an unfortunate bout with chronic diarrhea while in Mexico was to blame. Others suggested that a childhood injury to his spine had inexplicably now flared up, or that he had injured himself when jumping off a train. His malady was called, variously, “partial paralysis,” “neuralgia” or simply the “mysterious disease.”

If anyone guessed the real culprit, they were polite enough not to mention it publicly: in all likelihood Bissell had contracted syphilis in Mexico. Saltillo, where his regiment was posted before and after the Battle of Buena Vista, was a hotbed of venereal diseases; people later speculated that infected prostitutes there had done more harm to U.S. troops than Santa Anna’s army.

Ill as he was, Bissell consented to run for governor of Illinois in 1856 under the banner of the newly formed Republican Party. Abraham Lincoln’s name had initially been floated as a candidate, but Lincoln demurred, believing that only a former Democrat who opposed the contentious Kansas-Nebraska Act would have a chance of winning on the Republican ticket. Bissell was the logical choice: he had been an Anti-Nebraska Democrat, he was a war hero, he was popular. He was almost the perfect candidate.

The glaring drawback to Bissell’s candidacy was that he was not technically eligible for the office. According to the 1848 Illinois Constitution, anyone who had ever given or accepted a challenge to duel was barred from holding state office. Five years earlier, Bissell had been challenged to a duel by none other than Jefferson Davis, then a U.S. senator from Mississippi. Although the duel had never taken place, Bissell had accepted the challenge. Should he be elected governor of Illinois, he would have to swear an oath that he had never been involved in a duel, something he could not do without perjuring himself.

Bissell and his fellow Republicans came up with a rather disingenuous rationalization for Bissell’s continued candidacy: the challenge to duel had been accepted in Washington, D. C., not Illinois, and was therefore not subject to the dictates of the Illinois Constitution. It was slippery, but it worked: Bissell was elected with a plurality of almost 5,000 votes in 1856 and took the oath of office the following January. Although it is unclear how Bissell felt about his equivocation, some of his friends later suggested that torment over his perceived wrongdoing helped drive him to his early grave.

Bissell’s health continued to be fragile for his entire term as governor. Essentially housebound, he never visited the Capitol building and conducted all his official business from the second floor of the Illinois Executive Mansion. When he contracted pneumonia in early March of 1860, his weakened body was unable to fight off the disease, and he succumbed on March 17. He was 48 years old.

The public reaction was immediate and intense. “Death is a calamity under any circumstances,” noted the Illinois State Register, “but when a public functionary like that of an executive of a wealthy and powerful state is stricken down by the King of Terrors, the people have cause to mourn.”

Mourn they did. Military and civic organizations scrambled to pull together a funeral worthy of the head of state. In the days before embalming, it was considered prudent for interment to take place within a day or two of death, yet Bissell died on a Saturday and his funeral did not take place until the following Wednesday. This extra time allowed military regiments, judges, and state officials to travel from far-flung parts of the state to take part in the funeral procession.

On the day of the funeral, thousands of people bearing mourning badges converged on the Executive Mansion, its columns swathed in black bunting, to pay their last respects to the governor. Thousands more lined the street to watch the funeral procession wend its slow way from the Mansion to Bissell’s final resting place in Oak Ridge Cemetery. When it was over, the Illinois State Journal observed that the ceremonies surrounding Bissell’s funeral were “more imposing...than have ever taken place on any similar occasion in this State.” Little could they imagine that they would be called to stage an even more elaborate funeral just five years later.

Erika Holst is curator of collections at the Springfield Art Association.