Illinois governors in trouble

A history of corruption at the top

HISTORY | Erika Holst

Illinois was deeply in debt and its financial outlook was bleak. After a close gubernatorial race, the people of Illinois elected a wealthy Chicago-area businessman as their governor, hoping that his talent for making money would steer the state away from a looming fiscal crisis.

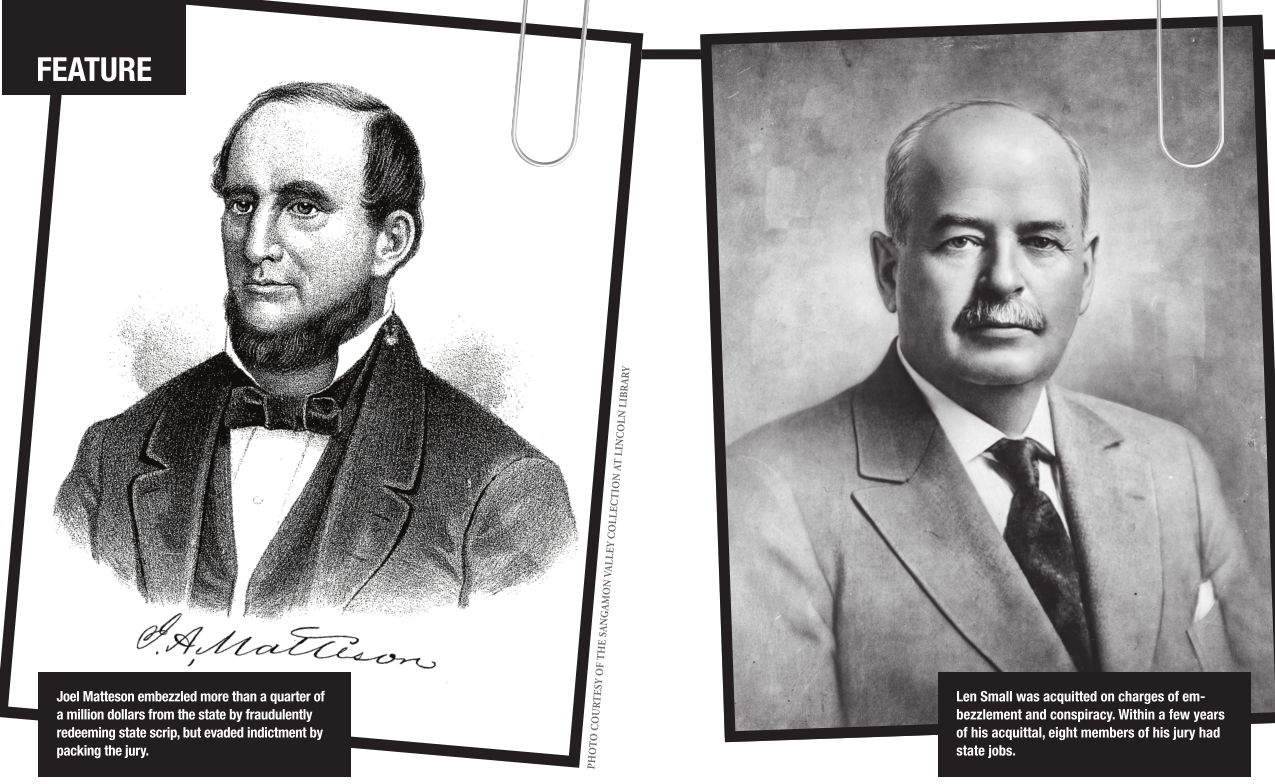

Instead, Gov. Joel Matteson, who held office from 1853 to 1857, ended up embezzling more than a quarter of a million dollars from the State of Illinois by fraudulently cashing in alreadyredeemed state scrip. Despite the overwhelming evidence of his guilt, however, Matteson evaded indictment and was never tried nor sentenced for his misdeeds.

In the murky world of Illinois politics, not all corrupt governors were indicted or convicted, and not all the indicted or convicted governors were necessarily corrupt. Moreover, some of the indicted or convicted governors were actually fairly effective administrators, while others were straight arrows who couldn’t manage to get much done in office. In the interest of understanding a little more about the political system about which we all love to complain, what follows is a guide to Illinois governors and the crimes for which they were accused and convicted, in chronological order.

Joel Matteson

Had the Illinois Constitution allowed for it at the time, Gov. Joel Aldrich Matteson might well have been elected to a second term. He was a skillful and personally charming man who had a fairly successful term in office. Among the highlights of his administration were the construction of the Governor’s Mansion (to which he advanced $10,000 out of his own pocket), the construction of a prison in Joliet and the enactment of a comprehensive common school system, financed by a two-mill tax and bolstered by local property taxes.

It wasn’t until three years after he left office that a shrewd state congressman caught wind of fraudulent state scrip in circulation and realized that the paper trail led straight to Matteson. The scrip had been issued in 1839 to help fund the construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. It functioned as a check drawn on the canal project, payable whenever funds became available. By the 1850s, all but $316 of the $338,554 scrip issued had been redeemed. In ideal circumstances, this redeemed scrip should have been voided and the name of the redeemer noted. The state’s financial recordkeeping had been sloppy, however, and this did not occur.

Instead, much of it found its way back to the canal offices in Chicago, where it sat forgotten for the better part of a decade.

Gov. Matteson stumbled across the redeemed but uncanceled scrip (essentially a trunk full of blank checks) in Chicago soon after taking office in 1853 and apparently decided it would be safer in his custody than in the canal offices. He ordered the clerk to pack the canal records and scrip into a trunk and send it to the governor’s office in Springfield. In 1856, while he was still governor, he started redeeming the already-redeemed scrip, trading it in for state bonds that he deposited, conveniently enough, into banks that he owned.

By the time anyone caught wind of what he was up to, he had fraudulently redeemed more than $200,000 worth of scrip on the sly. An official investigation was convened in 1859, two years after he left office, and Matteson’s guilt quickly became apparent. Matteson maintained his innocence, claiming that he had purchased the scrip in good faith. Then, fearful of his reputation and eager to avoid arrest, he offered to repay the state for the scrip he hadn’t stolen and chalk it up to an honest mistake.

The state’s high-ranking Republicans were not about to let a corrupt Democrat off the hook that quickly, and a grand jury was convened in the Sangamon County Circuit Court to consider an indictment. The proceedings were highly unorthodox. Matteson himself was present, contrary to law, along with a team of attorneys later accused of tampering with the jury. After twice voting to indict, the jury reversed itself and voted 12-10 not to pursue criminal charges.

The state legislature, however, voted to hold Matteson financially responsible for the fraud, and the Sangamon County Court eventually ruled in 1863 that Matteson owed the state $253,723.77. His private residence in Springfield (across the street from the governor’s mansion) was sold at auction for $238,000 to pay the debt, and Matteson and his family fled to Europe. He died in 1873 with his reputation in tatters.

Len Small

Len Small, a Chicago Republican who was in office from 1921 to 1929, enacted several popular measures as governor of Illinois. On his watch, hanging was replaced with electrocution in capital punishment cases. World War I veterans received a state

bonus. The state conservation department was established to administer

fish and game codes, promote forestry and prevent water pollution. Locks

and dams were built on the Illinois River near Utica. And state aid to

schools was regulated to better serve weaker districts, much like what

the current effort to reform the school aid formula is trying to

accomplish.

Small’s

biggest achievement, however, was building more than 7,000 miles of

paved roads in Illinois. During his administration, Illinois added more

miles of pavement than any other state in the Union. These roads were

well-engineered and built economically. And because Small was a machine

politician to his core, they were also used as political leverage. As

Dick Simpson, professor of political science at the University of

Illinois- Chicago, put it, “Len Small was part of the Republican

machine. He was pretty corrupt.” In the case of the new roads, Small

rewarded counties that voted for him with their share of pavement and

punished those that opposed him by purposely shorting them.

Small’s

proclivity for punishing his political enemies landed him in hot water

less than a year after he took office. After he slashed Attorney General

Edward J. Brundage’s appropriation bill, Brundage retaliated by

indicting Small for conspiracy, embezzlement and operation of a

confidence game. The alleged crimes went back to Small’s second term as

the Illinois State Treasurer, from 1917 to 1919. Small was accused of

having deposited Illinois state funds in a dormant bank, lending those

funds to Chicago businessmen at six percent interest, reimbursing the

state with two to three per cent interest, and pocketing the difference.

Small maintained his innocence throughout, claiming that he wasn’t

aware of what was being done in his name and that the charges had been

trumped up by his political enemies.

Small’s

trial took place in the Lake County Circuit Court over nine weeks in

the spring of 1922. After just an hour and a half of deliberation, the

jury acquitted Small of all charges. Eight of those jurors wound up with

state jobs, as did the presiding judge’s brothers.

In

1927, the case returned to court as a civil trial initiated by the

Illinois attorney general. The Supreme Court ruled that Small owed the

people of Illinois $1 million in interest from the state funds he lent,

though the figure was later reduced to $650,000. Small raised the money

by forcing state employees and contractors to pay into his defense fund.

It is unclear if any of the money he paid back came from his own

pocket.

William Stratton

William

Stratton, who served as governor from 1953 to 1961, was indicted for

tax evasion four years after he left office, thus earning himself a

place on the list of Illinois governors who have been indicted or

convicted of a crime. But there are many who argue that he does not

deserve to be lumped in with Illinois’ corrupt governors.

Stratton’s

track record as governor is one of the more illustrious in Illinois

history. Like Len Small, Stratton added more than 7,000 miles of new

road to Illinois, along with 638 new bridges. Unlike Small, however,

Stratton did this without wielding his roads as a weapon of political

coercion. Instead, he used funds raised by recent increases in the gas

tax and drivers’ license fees, coupled with a bond issue, to finance the

construction of multilane interstate highways, including the expressway

and tollway system around Chicago. Stratton’s administration was also

responsible for bond issues that financed the development of the state

universities in Chicago and Edwardsville, as well as the expansion of

the Northern, Western and Eastern Illinois universities. He opposed a

state income tax and backed reform of a state sales tax that would

bolster revenue in less prosperous downstate municipalities. An

outspoken critic of racial segregation, he introduced a bill to create a

commission to encourage fair employment practices. This bill died in

the Senate.

In 1965,

Stratton was charged with failing to report $95,595 of taxable income

earned during his second administration, thereby evading $46,676 in

taxes. The money came from campaign contributions, which Stratton used

for a variety of personal purposes, including the construction

of a personal lodge in Cantrall, clothing for his wife and a horse for

his daughter. U.S. Sen. Everett Dirksen, the defense’s star witness,

argued that, while the campaign funds were not taxable income, such

personal use was perfectly legal if the donor placed no restrictions on

his or her gift. The court agreed, and Stratton was acquitted of all

charges. “These days it would be clearly illegal and he’d go to jail,”

Simpson said. “Jesse Jackson Jr. did exactly what Stratton did – used

campaign funds to fund personal expenses.”

Otto Kerner

Like

his predecessor in office, William Stratton, Otto Kerner, governor from

1961 to 1968, could boast of several accomplishments during his two

terms as governor of Illinois. Handsome and well-connected (his

father-in-law was former Chicago mayor Anton Cermak), he was known

during his governorship as Mr. Clean. It wasn’t until after he left

office that he became the first Illinois governor in the 20 th century

to be convicted on federal charges.

Socially

progressive, Kerner’s administration made large strides in health and

human services. The Department of Public Aid and the Department of

Children and Family Services were established on his watch. He was

instrumental in making birth control available to married women. And he

facilitated the construction of six new mental health clinics boasting

programs that became a model for national health reform.

Kerner

was also a committed proponent of civil rights. He facilitated the

creation of fair employment practices and issued an executive order

prohibiting discrimination in the sale and rental of real estate. In

1967, President Lyndon Johnson named him chairman of the National

Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders (also known as the Kerner

Commission), which was tasked with investigating the cause of recent

race riots within the United States. In the report, Kerner denounced

racial discrimination, warning, “Our nation is moving toward two

societies, one black, one white – separate and unequal.”

Kerner’s

legal troubles began in 1961, when he bought stock in Arlington Park

and Washington Park racetracks from the tracks’ manager, Marjorie

Everett, at a deep discount. During the Kerner administration, the

tracks received favorable racing dates and other political favors. The

transaction came to light in 1966, when Everett deducted the value of

the gifted stock from her federal income tax returns under the

assumption that bribes were part of the cost of doing business in

Illinois, and in 1968, Kerner reported profits from the sale of the

stock on his own income tax returns. In 1973 Kerner was tried and

convicted on 17 counts, including mail fraud, conspiracy and perjury. He

was fined $50,000 and sentenced to three years in federal prison. Less

than two years later, he was diagnosed with terminal lung cancer and

released on emergency parole. Today some political analysts view Kerner

as having been led astray by his faith in Theodore Isaacs, his campaign

manager and financial adviser, who was tried and convicted alongside

Kerner. According to Charles Wheeler, director of the Public Affairs

Reporting program at the University of Illinois Springfield, “Isaacs was

a bad apple, and Kerner relied on him.”

Dan Walker

Dan

Walker, who held office from 1973 to 1977, is one of four Illinois

governors who were sentenced to federal prison, but unlike the others,

Walker’s crimes were committed after he left office. In essence, he was a

criminal who happened to have been a governor, not a criminal governor.

As such, Wheeler objects to his inclusion on the list of corrupt

Illinois governors. “I would look at a corrupt governor as a governor

who did corrupt things in his official capacity. Dan Walker’s conviction

had nothing to do with him being governor,” he noted. “We have enough

public officials that get convicted of crimes that involve abuse of the

public trust; we don’t have to up the body count by adding governors who

happened to commit crimes after they left office.”

A

combative governor, most of Walker’s term was spent locking horns with

the legislature, which he openly disdained, and Chicago mayor Richard

Daley, whose political machine Walker openly despised. Still, he managed

to sign legislation requiring disclosure of campaign contributions and

issue an executive order prohibiting corrupt practices by state

employees. His administration also created the Illinois Department on

Aging.

Walker was

defeated in the 1976 Democratic primary by Michael Howlett, who went on

to be defeated by James Thompson in the general election. A private

citizen again at 55 years old, Walker engaged in a series of

unsuccessful business ventures. In 1983, he became chairman and CEO of

the First American Savings and Loan Association of Oak Brook. In that

capacity, Walker loaned a private contractor $279,000, and then

personally borrowed $45,000 from that individual, a practice which

constituted bank fraud. Walker’s personal borrowing from the bank also

exceeded the limit allowable by federal banking regulations; he used

part of those funds to pay for repairs to his yacht. In 1987, he was

charged with bank fraud, perjury and falsifying financial statements.

Walker pled guilty and was sentenced to a maximum of 15 years in prison

and a fine of $505,000. He was released from prison and placed on

probation after 18 months in the federal penitentiary.

George Ryan

By

most accounts, George Ryan, governor from 1999 to 2003, is a nice guy.

Ironically for a man sentenced to federal prison, he was widely regarded

as a man you could trust. And, like many of his predecessors, Ryan was a

skillful administrator who could boast of many significant achievements

during his administration.

Among

them, Ryan improved the state’s technological infrastructure, provided

billions of dollars to improve transportation, and committed record

levels of funding to education. He issued a moratorium on the state’s

use of the death penalty and, just before leaving office, commuted to

life in prison the sentences of all 167 prisoners on Illinois’ death

row. The latter action earned him a nomination for a Nobel peace prize.

On

the other side of the ledger, Ryan’s public life was marred by a series

of scandals. In 1994, six children were killed in a car accident

involving a semi truck. The driver, Ricardo Guzman, had obtained his

license by bribing someone in the Illinois Secretary of State’s office.

George Ryan, at the time, was Secretary of State. Upon investigation, it

came out that the bribe money went into Ryan’s campaign fund. Ryan

denied involvement in the scheme, but, as Simpson noted, “He was

orchestrating a Republican machine operation. He certainly had to

understand that he was getting kickbacks from his employees, who were

getting it from somewhere.”

The

probe into the licenses-for-bribes scandal eventually reached Ryan in

the governor’s mansion. In 2003, Ryan was indicted on 22 counts,

including racketeering, bribery, tax fraud, money laundering, extortion

and obstruction of justice. Among his crimes were using campaign funds

for personal use, steering state contracts to friends and associates,

accepting gifts in return for favors as governor, lying to investigators

and attempting to block the state investigation into corruption in the

Secretary of State’s office. Ryan was convicted in 2006 and sentenced to

six and a half years in prison and served the full term. He was

released on July 3, 2013.

Rod Blagojevich

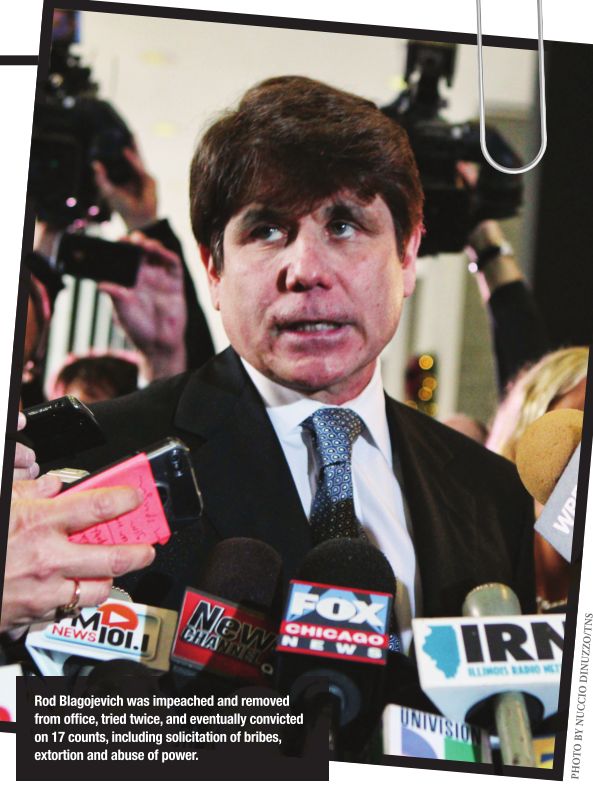

According

to Wheeler, “Rod Blagojevich was certainly the most corrupt in recent

memory.” His analogy: if Ryan went to jail for shoplifting Slim Jims

from the 7-11, Blagojevich went to jail for sticking the place up and

demanding all the cash in the register. Blagojevich was governor from

2003 to 2009.

In the

wake of George Ryan’s scandalplagued administration, Blagojevich ran on a

platform of “ending business as usual” and bringing change to

Springfield. One of his first acts as governor was to sign into law the

toughest ethics reform package in Illinois history. Yet according to the

U.S. attorney’s criminal complaint, filed in 2009, Blagojevich and his

co-conspirators started plotting on how they could use the governorship

to enrich themselves even before he took office. Taking the state’s helm

when Democrats also controlled both houses of the legislature,

Blagojevich was able to pass many progressive measures, including

creation of a state Earned Income Tax Credit, expansion of children’s

health programs, and a ban on discrimination based on sexual

orientation. Yet Blagojevich struggled with state spending, exacerbating

the looming pension crisis and at one point proposing to go so far as

to sell or mortgage the Thompson Center in Chicago to raise funds.

In

2009, Blagojevich was arrested. Among his alleged crimes were

soliciting bribes to fill Barack Obama’s recently vacated Senate seat;

shaking down Children’s Memorial Hospital for a campaign contribution in

exchange for the release of $8 million of state funds; and seeking

campaign contributions from individuals or companies who received

political favors or state contracts from the Blagojevich administration.

Blagojevich was impeached and removed from office in 2009. Of the 24

charges for which he was indicted by a federal grand jury, he was

convicted on one, and a mistrial was ordered for the other three. The

case was retried, and Blagojevich was found guilty on 17 of 20 counts.

In 2012 he began serving a 14-year prison sentence at the Federal

Correctional Institution in Littleton, Colorado.

Why Illinois and what to do?

Why

does Illinois have such a lousy track record with its public officials?

Why is it third on the list of most federal public corruption

convictions per capita in the United States? Simpson and Wheeler agree

that the answer lies on the way Illinois has approached government from

the earliest days of its statehood, when it inflated the number of

residents within its borders to achieve statehood.

Illinois,

Wheeler explains, has an individualistic view of government, whereby

the political system is seen as a marketplace where one can improve

oneself financially and socially. “The basic idea is helping yourself

and your friends, not about instituting a perfect form of governance,”

Wheeler said. That “what’s-in-itfor-me” attitude gave rise early on to

machine politics, in which political machines are used to steal

elections and patronage is used to pay off the political footsoldiers.

There

is hope for Illinois, but, as Simpson cautions, “there is no silver

bullet. It will take a long time, but everyone can do their part to help

eliminate the pattern of corruption.” In his book, Corrupt Illinois: Patronage, Cronyism, and Criminality, Simpson

outlines a multipoint plan of action to steer Illinois away from its

pattern of political corruption that includes campaign finance reform,

expansion of civic education, election of reform-minded individuals and

holding public officials to a higher standard of transparency and

accountability.

“It

will take time. It’s taken us 150 years to establish this pattern of

corruption, so it will take several decades to change,” Simpson said.

But it can be done.

Erika Holst is curator of collections at the Springfield Art Association and author of Wicked Springfield: Crime, Corruption, and Scandal During the Lincoln Era.