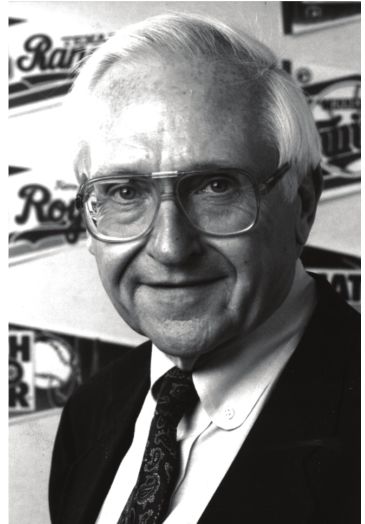

Nov. 5, 1933-Aug. 4, 2014

For political intelligence, he was the man to know in Springfield

A single word comes to mind when discussing the life of Gene Callahan of Springfield: Loyal.

Loyalty was not something just sprinkled throughout his adult life. It was a major part, beginning with his family and including people and experiences of a lifetime.

Callahan left his job as reporter and columnist with Springfield’s Illinois State Register in September 1967 to work as assistant press secretary for Lt. Gov. Samuel Shapiro. (Callahan liked to point out that the job paid less than his newspaper work.) He stayed with Shapiro through the 1968 campaign for governor. Callahan had known Shapiro since childhood when his father had worked as a volunteer for the politician. The families shared a devotion to the Democratic Party. Callahan felt a sense of loyalty to Shapiro, and later to his memory.

His first relationship with Paul Simon other than as a source for newspaper columns occurred in 1967 when Callahan worked as a public relations volunteer in downstate areas. As compensation for expenses, Simon sent Callahan a monthly check for $35. Callahan never cashed any of the checks. There was an instant personal connection between the two. Callahan said, “I really liked Simon.” That led to a shared loyalty that included work on Simon’s staff from 1969 to 1973. He served as a pallbearer at Simon’s funeral service, and as a founding member of the Simon Institute’s board of counselors. Callahan sustained the loyalty bond with political campaign support for Simon’s daughter, Sheila.

The stories of loyalty to his family would fill a book. Two are worth telling. Callahan’s long-lasting loyalty to baseball had two major pieces. First, he was a diehard St. Louis Cardinals fan. Second, his son, Dan, lived a life of involvement in the game. Dan played baseball, including time with two major league organizations. He served 16 seasons as baseball coach at Southern Illinois University. His loyal boosters included his parents, who religiously attended the games. After a long bout with cancer, Dan died Nov. 15, 2010, at age 52. Gene served from 2000-2004 on the SIU board of trustees.

When Callahan’s daughter, Cheri Bustos, chose to run for public office, she had the benefit of his decades of work in politics. In 2012 she was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives from Illinois, with availability of her father’s enormous list of friends, associates and political contacts. Loyalty to Cheri was more than distant parental cheering. A day before he died, Callahan appeared at a fundraiser for Cheri’s campaign. She won re-election.

Callahan first met state Rep. Alan J. Dixon in 1961 at the St. Nicholas Hotel bar in Springfield. They quickly discovered common interests and ideas. The friendship grew during Callahan’s years working for Simon. At a critical time in Dixon’s 1970 campaign for state treasurer, he needed help with media. Simon agreed to “loan” Callahan for the effort. (Dixon returned the favor during Simon’s 1990 re-election campaign.) After Simon lost his bid for governor, Dixon asked Simon for permission to talk to Callahan about a job in 1973. Simon said OK. Callahan joined Dixon’s staff and remained in Springfield and Washington until his boss lost a bid for re-election to the U. S. Senate in 1992. Callahan’s loyalty to Dixon knew no limits, and the two remained in close contact as friends and political activists. Callahan served as eulogist at Dixon’s funeral in July.

All who had any association with Callahan over the years knew of his loyalty to the Democratic Party, state and national. But his loyalty was not blind. He disassociated himself from Gov. Rod Blagojevich for many reasons. When political campaign consultant David Axelrod – who worked for Simon in 1984 and 1988 and later became a top aide to Barack Obama – turned on Dixon during the 1992 campaign and supported a competitor with angry public accusations, he made Callahan’s list of political traitors.

As work for Dixon ended, Major League Baseball commissioner Bud Selig hired Callahan as a lobbyist in Washington. One of Selig’s concerns was protecting the game’s exclusion from antitrust laws, which required constant contact with members of Congress. The match was made in heaven with Callahan, not only a devotee of baseball, but connected with senators of both parties on The Hill, working baseball’s issues.

For journalists, writers of books, elected public officials, those who wanted to run for public office, and political junkies, the man in Springfield was Gene Callahan. He preferred to do business by telephone or in person, as long as it didn’t interfere with his morning walk. No email or other social media gimmicks for him. He appeared on radio shows and at events where politics was the topic. Callahan did not discriminate by political party either. He also had Republican information and generously provided it – with an occasional “not for publication.” His loyalty stretched far and wide.

When Bob Hartley was editor of Lindsay-Schaub newspapers in Illinois he met Gene Callahan during the 1968 gubernatorial campaign when Callahan worked for Gov. Samuel Shapiro. Over the years Callahan provided helpful guidance for Hartley’s political writings.