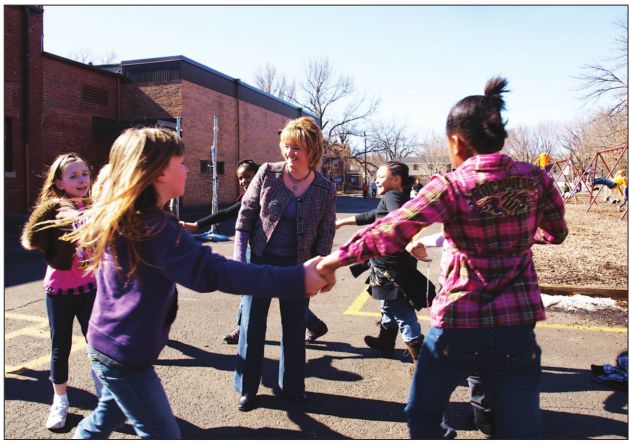

It’s still early in Jennifer Gill’s tenure as District 186 schools superintendent. But so far people like what they see.

EDUCATION | Bruce Rushton

Jennifer Gill wasn’t always a leader.

Her days at Springfield High School were busy ones. She spent a year on the student council. Worked on the yearbook staff during her senior year in 1987. Belonged to the Spanish Club, the Philo Club and the Red Cross Club, the latter two organizations dedicated to doing charitable work in the community. She did not hold a single office in any of the groups – someone else was always president or treasurer or secretary.

“To be honest, I didn’t do those things at the university level either,” Gill confesses. “I was never the president or vice president type of person at my younger age. I might be a late bloomer.”

She is more than making up for it. Gill is now superintendent of a district that has gone through both leadership and financial turmoil. In some ways, her arrival was a soft landing, one year removed from the ouster of former superintendent Walter Milton and school board elections that resulted in four new faces on a board that cut the budget by $5.5 million, largely by slashing teaching positions, just before Gill started work in May.

Gill has not yet faced a major crisis, but there is still plenty on her plate, much of it taken on voluntarily. No one is forcing her to be on the board of the YMCA, but there she is. Similarly, she sits on the boards of the Greater Springfield Chamber of Commerce and United Way of Central Illinois.

The roots are deep. Her husband and then-classmate took her to the junior prom at Springfield High School (but she says they didn’t start dating in earnest until they were both college students at Eastern Illinois University). In high school, she was a lifeguard and swimming instructor at the same YMCA where she now serves on the board of directors. She recalls giving swimming lessons to children and their mothers, and she also taught swimming in a terrified-of-water class aimed at adults.

“That’s where I got the bug, that I might not be that bad a teacher,” says Gill, whose parents were both teachers.

She hasn’t been a classroom teacher since 1996, when she left her third-grade classroom at Wanless Elementary School to become an administrative intern at Franklin Middle School. Except for three years after college at Eastern Illinois University, when she taught fifth-graders in Jacksonville, and a two-year stint as an administrator in Bloomington for McLean County Unit District 5 before she became superintendent in Springfield, she has spent her entire working life in Springfield School District 186.

Her enthusiasm and energy are apparent as Gill bounces from one community event to the next, typically working 12-hour days. She recently helped the Salvation Army kick off its bell-ringing campaign with songs at White Oaks Mall, then dashed to an evening forum on race relations at Southeast High School sponsored by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She arrived just in time to hear former NAACP branch president Ken Page tell the gathering that the district should be sued for failing to educate minorities.

Gill doesn’t respond, but later says that litigation won’t solve problems in a district that has struggled to improve graduation rates that have stayed around 65 percent for years and dismal test scores at all grade levels.

“It makes me want to do better when I hear things like that,” Gill says during an interview in her office. “Those feelings and emotions that he feels are ones that I feel as well. … I want to work with our community so that those feelings don’t exist.”

During an earlier forum in September, also hosted by the NAACP, Gill heard the message loud and clear. Armenta Johnson, who has two grown sons, blasted the district for expelling students and for allowing kids to play sports despite poor grades.

“I want our children to know how to read, to write, to add, to subtract and to think,” Johnson said. “They’re flunking out. They’re not employable. We have gatherings like this elsewhere, and we’re all saying ‘We need to improve the schools, we need to improve parenting, communication.’ Instead of saying we need to, when are we going to? What are we going to do? When are we going to do something?” Johnson’s remarks prompted scattered applause and acknowledgement from Gill that the district needs to improve. The district last year suspended 2,926 students, Gill said to the crowd, which is roughly one-fifth of the students in the district.

She offered no specific solution to either reduce suspensions or improve academic performance, saying that the district needs to work with the community and listen.

“I know our graduation rate is not where I want it to be,” Gill said. “It’s a two-way street. It’s talking together. It’s working together.”

If Gill could replicate herself in Springfield schools, her job might be easy.

She has never before been a district superintendent, but Gill has bona fides as a principal in Springfield schools, particularly at McClernand Elementary School, where she was principal from 2008 until 2012.

If ever a school was hopeless, McClernand was, at least on paper, when Gill arrived. More than 90 percent of students lived in poverty and more than 40 percent of the student body either transferred into the school or transferred out during the year, challenging educators to quickly assess student needs and abilities. Just 43 percent met state standards on reading tests while 53 percent met standards on math tests.

Improvement at McClernand under Gill’s tenure was dramatic. By 2010, 61 percent of McClernand’s students met state standards in reading tests, an improvement of 18 percentage points in two years. Results were even better in math, with 76 percent of McClernand students meeting state standards in 2010 tests. It’s hard to argue that Gill doesn’t deserve the credit. Since she left McClernand in 2012, test scores have plummeted, with just 26 percent of McClernand students meeting reading standards in testing this year and 43 percent meeting math standards. Performance in science tests has also declined, from 70 percent meeting state standards in 2012 to 49 percent meeting standards in testing this year.

How

did she do it? “I think with McClernand, the secret to success was just

an undying want for those kids to be successful, bringing the parents

to the table, having opportunities for them to really be part of their

student’s learning,” Gill offers. “And also a laser-like focus on the

core instruction and what we need to do for each and every student.”

Nearly 70 percent of the district’s students are living in low-income homes, but Gill doesn’t use poverty as an excuse for poor academic performance.

“Poverty is not an illness or a condition, it’s just something that people are dealing with,” Gill says. “We don’t look at that as determinant of them having success or failure in life. It’s more about whether or not they have the same opportunities to go to school and to be part of a rich, rigorous curriculum and having people pulling for them from all sides, telling them ‘You can do this.’” That pull must come from both inside and outside schools, Gill says. At McClernand, she earned a reputation for working with community groups such as the Enos Park Neighborhood Improvement Association and the Springfield Art Association, which has offices across the street from the school. Parents were welcomed into the school. Mothers ate breakfast with their kids at the start of the school day. There was talk of turning McClernand into a magnet school with a focus on the arts, an idea that never reached fruition. But Steve Combs, past president of the Enos Park Neighborhood Improvement Association, doesn’t blame Gill.

“When we went in and talked to superintendent Milton, it just didn’t seem like that was a priority or a major concern at the time,” recalls Combs, a retired teacher who wrote a recommendation for Gill when she sought the superintendency. “I never felt she could say to us, the neighborhood, ‘We’re going to make this a magnet school.’” Combs says that he isn’t concerned that Gill has never before run a district.

“She is so personable, I think she can rise above the bumps and waves of a board that, hopefully, will be supportive of her,” Combs said. “She knows it (the district) isn’t where it should be or where she wants it to be.”

Can she make tough calls, especially ones that could hurt teachers and other employees whom she’s known for years? Combs said that he’s asked two McClernand teachers whether Gill is tough enough.

“I’ve asked the same thing: Is she too close to you guys?” Combs said. “Their response was, ‘No, we trust her. We realize there are issues that we may not like, but we like her.’” Gill also earns high marks from the Rev.

Tom Christell of Grace Lutheran Church, where members have volunteered to work in the McClernand library, help kids with homework, prepare holiday baskets for families of needy kids and otherwise pitch in to help students and their families.

“It’s incredible,” Christell says. “Some of these schools, kids come, even in the winter, with no socks.”

Christell remembers Gill for her presence. While church members worked with different people on the McClernand staff, Gill was a constant.

“Jennifer was always there, always thankful, always appreciative,” Christell recalls. “She kept us up to date on what was going on in the school. … I’m just hoping she will continue to do the kind of job I’ve seen her do in the past.”

Gill as a senior at Springfield Hight School.

From McClernand, Gill went to Bloomington in 2012 to take a job as director of teaching and learning for McClean County Unit 5.

It was a high-level post where she sat on the cabinet of the superintendent of a district with 14,000 students. In addition to overseeing curriculum development, one of her first tasks was administering the distribution of 1,100 netbooks so that every sixth-grader would have a take-home computer in class, a program that cost the district $800,000.

She says she was contacted by a third party about the Bloomington job and didn’t jump at the chance.

“I actually turned it down twice before I went to an interview,” Gill says. “Anybody who knows me, including my husband and family and my parents, it was the hardest decision I ever made in my life. It was a very emotional one for me. It’s still emotional to talk about.”

Not having her two children enrolled in the schools she oversaw went against her belief that administrators should live in the district that employs them, Gill says. On the other hand, she didn’t want to disrupt her children’s academic lives by pulling them out of Springfield schools where they were doing well. And so she commuted.

“I’m a much better person because I did it,” Gill says. “I learned things, how to work with teachers across buildings to help them understand standards. I got to sit in on budget meetings.”

Even as Gill was starting work in Bloomington, Milton’s relationship with the Springfield school board was crumbling, with board members criticizing the superintendent for what they said was a lack of candor during budget discussions and a failure to live within financial means.

It didn’t help matters when the board reached a secret agreement with Milton that called for him to leave the district in March 2013 in exchange for nearly $180,000. Piled on top of conflicts, accusations and mistrust between the district and the community was talk of asking voters to approve a property tax increase for schools. Voters replaced school board president Susan White, who had presided over the mess, and three other board members elected that spring were newcomers.

School board member Adam Lopez, who ran unopposed for the school board in 2013, says that he invited Milton to breakfast at Charlie Parker’s shortly after the election and the ousted superintendent, even before a search had begun for his replacement, had a recommendation.

“He sat down with me at breakfast and said ‘Adam, the next superintendent should be Jennifer Gill,’” Lopez recalls. “Isn’t that crazy? … The biggest thing he said was, she’s from Springfield. He said she’s going to be the future of 186. And he was correct.”

Besides never having run a school district, Gill also had not completed her doctorate degree. Nonetheless, she applied for the job, and she says that she wants to end her career with the district.

“I had no idea at the time what kind of superintendent the board was looking for,” she says. “I was interested in this superintendency.”

She ended up with a three-year contract that pays her $195,000 a year, considerably less than her predecessor earned, with raises predicated on annual performance evaluations. So far, she wins high marks from school board members.

Board members say she’s transparent and alerts them to stories in the works so that they’re not caught by surprise when they see something in the newspaper or on television. They like the way she shows up at meetings and events throughout the community. Board member Lisa Funderburg says Gill’s biggest strength – and weakness – is her work ethic.

“She’s a hard worker,” Funderburg says.

“She’s everywhere – that’s a comment I’ve heard from a lot of people. … I hope she doesn’t burn herself out. She’s giving it her all. No one can say she’s not trying.”

Board member Chuck Flamini, a former district employee who has been everything from a teacher to an assistant superintendent to school board president, says Gill has done a good job developing a security plan for the district in the wake of two incidents in which students were caught with guns at school.

“What I see is a very focused person,” Flamini said. “I see someone who understands, very completely, instruction and how you have to recognize it to be able to make things better for the schools and the kids. … This is the test of her lifetime, and I think she’ll do fine.”

Can she get the same results district-wide that she achieved at McClernand? Board member Donna Moore says she’s expecting it and she’s already seen it at Washington Middle School, where the principal is mentoring students who need extra help. One student who had been getting D’s and F’s has been getting C’s and D’s with help from the principal, she says.

“I talked to Jennifer about it,” Moore says. “She said ‘Oh, yeah – all the principals. They’re going to mentor kids.’ It has been done as a smattering. When it’s an expectation that comes from the top – you will do this – it has broad impact.”

Then there are folks like Page, the former NAACP president who has said that the district should be sued for failing to educate minorities.

“I have nothing against Jennifer Gill,” Page says. “I don’t even know her. It’s about educating our kids, all of our kids. … Black students are not where they should be. The district always says that and gets away with saying it. We’ve talked enough. I don’t want to sit on any more committees or any forums. We just hear the same thing over and over again. Now it’s time for you to produce something.”

Teresa Haley, current NAACP president, says the verdict isn’t in, but she’s encouraged by what she’s seen so far. The new superintendent has her cellphone number, Haley says, and she has Gill’s number.

Haley

praises Gill for issuing a memo instructing faculty at schools to avoid

discussing the shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson by police when a

grand jury issues a decision on whether to indict the officer who pulled

the trigger. Families should have time to discuss the issue with kids,

she wrote, and while social workers and psychologists will be available

to talk to students who feel the need when the grand jury decision is

announced, teachers should concentrate on curriculum and lesson plans

instead of starting conversations about Ferguson.

By inviting classroom discussions of Ferguson, Haley says the district risks alienating students with one point of view from students who have another.

“Our position is like Jennifer’s,” Haley said. “Somebody can say something in the classroom like ‘He got what he deserved.’ Now, you’ve stirred up some stuff in a kid.”

Haley said she’s seen signs that the district will no longer promote kids to the next grade level if they haven’t mastered subjects. And she says that Gill has asked the NAACP about providing mentors to kids who have fallen behind in school. Not everything is perfect, says Haley, who says that the district needs to hire more minority teachers. But it’s a good start.

“I like her personally,” Haley says. “I think she’s committed. She’s caring. If she doesn’t know the answer, she doesn’t make it up. … Until we see something different, we don’t have a problem with her.”

Mayor Mike Houston is also a fan. “I’m totally impressed with the job that she’s done,” Houston said. “I think people have forgotten that we had a previous superintendent. I think her approach to the job and to the community has really wiped out any negative thoughts that may have been there.”

Despite low graduation rates and poor scoring on standardized tests, it’s possible to get first-rate education at District 186, Houston says, but the district needs new buildings. He has called for the formation of a blue-ribbon panel to analyze the district and issue a report. Assuming the report is positive, Houston has called for a referendum to increase property taxes to pay for new construction.

The blue-ribbon panel would be organized by the Greater Springfield Area Chamber of Commerce. Gill says she welcomes scrutiny.

“I’m never going to turn away the opportunity to share knowledge that I have in a transparent way about our data, about our finances, about the inner workings of our system,” she says. “I’m happy to do that. … Without someone answering questions directly and being truthful, people don’t have trust in our system.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].