Pot biz lights up

Medical marijuana investors count on secrecy, profits and expansion

A RESCUING ILLINOIS REPORT | Kari Lydersen

The 900 block of West Lake Street is the northern border of a meatpacking and warehousing district now occupied by trendy Chicago restaurants and bars.

The 900 block of West Lake Street is the northern border of a meatpacking and warehousing district now occupied by trendy Chicago restaurants and bars.

If this company, Clinic West Loop, gets its way, that stretch of road will also be home to one of the 13 medical marijuana dispensaries scheduled to open next year in Chicago as the state rolls out the medical cannabis pilot program created by legislation passed and signed into law by Gov. Pat Quinn last year.

A subsidiary of a consortium called Green Thumb Industries (GTI), Clinic West Loop has applied for licenses for four marijuana cultivation centers and three dispensaries statewide.

Their team includes The Clinic Colorado, a nonprofit policy and lobbying group that also operates six clinics in Denver; Hillard Heintze, a security risk management firm co-founded by former Chicago Police Superintendent Terry Hillard; and Terrance Gainer, former Illinois State Police director and former Chicago police detective.

While it’s ironic that a couple of former cops are now eager to provide security expertise for marijuana providers, Clinic West Loop is just one of several hundred applicants awaiting the state’s announcement, expected in December, that determines who will get a stake in what is expected to become a booming and highly lucrative new industry.

But getting in on the ground floor of Illinois’ medical marijuana business isn’t cheap or easy, a BGA Rescuing Illinois investigation details. The opportunity is drawing an elite crowd of applicants from the world of high finance, along with a flurry of technical, legal and marketing experts from states where medical marijuana has been legal for years.

That rush of big money and power, along with Illinois’ sorry track record of tricky deals, has some applicants questioning whether selections will be influenced by cronyism, politicking and mystery.

“Plenty of people contacted us saying they would like to apply for one of these licenses, but they think the application process is going to be rigged and corrupt and they don’t want to waste the money if it’s going to be someone’s brother-in-law getting the licenses,” said Dan Linn, executive director of the Illinois chapter of the National Organization for Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML).

State officials disagree. They vow an honest selection process, free of influence peddling, and assert that any mistakes or problems made along the way will be corrected.

“No law is perfect, no set of rules is perfect, and there will probably have to be adjustments – I’ll be there to make those,” said State Rep. Lou Lang, D-Skokie, lead sponsor of the law that created the fouryear pilot program and presumably laid the groundwork for future and potentially expanded medical marijuana legislation.

Applications roll in

In total, the state received 214 applications for up to 60 dispensary licenses and 159 applications for 21 cultivation centers statewide, with each application costing $5,000 and $25,000 to file, respectively.

Cultivation

center applicants must show proof of $500,000 in liquid assets and post

a surety bond of $2 million to the Illinois Department of Agriculture;

dispensary hopefuls must show $400,000 in liquid assets. There will be

two cultivation centers in Chicago and the northern suburbs.

These

numbers show just how big people expect Illinois’ medical marijuana

industry to become. Their hopes are bolstered by financial data from

other states with medical marijuana and projections regarding full

marijuana legalization, which some see in the cards for Illinois down

the line.

For example,

Michigan brought in $10.9 million in fees from its medical marijuana

program last year, providing significant revenue beyond the $4 million

the program costs to administer. And the blog Wallstcheatsheet.com

recently predicted that Illinois is among the seven states with the

greatest potential revenue if marijuana were fully legalized.

It estimated that an Illinois marijuana industry could bring in $544 million in revenue, and $126 million in taxes to the state.

The

teams applying for cultivation center and dispensary licenses appear

typically to be made up of successful local businesspeople from a

variety of sectors along with wealthy financiers and expert growers and

sellers from states like California and Colorado where medical marijuana

has been legal for years.

“This

is the hottest business opportunity in the United States,” said

attorney Bradley Vallerius about legalized marijuana in general. “An

already existing market made legal. An opportunity to get in on the

ground floor of a new industry, to become the Budweiser of marijuana, to

secure family wealth for generations.”

Checks and balances

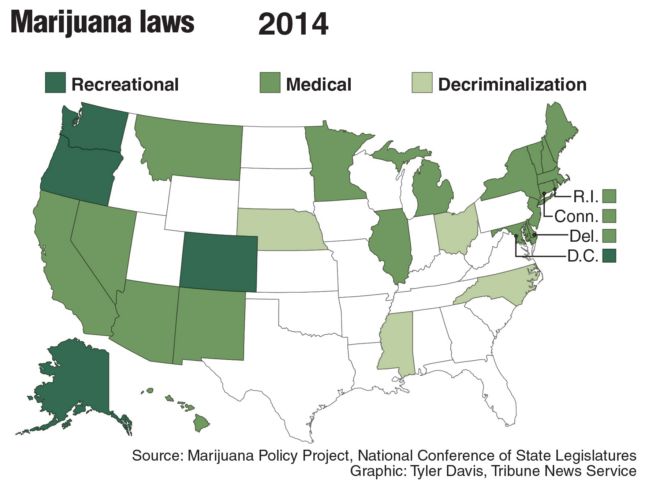

More

than 23 states and the District of Columbia have legalized medical

marijuana and four of those states and Washington, D.C., have legalized

marijuana for recreational use.

Illinois’

medical marijuana law is among the country’s strictest, many experts

say, with a relatively limited list of three dozen qualifying medical

conditions for patients, high fees and standards for dispensary and

cultivation center owners, strict operational rules and a promise of

tight regulation.

Applicants

had to propose extremely detailed security plans, undergo background

checks, submit personal tax returns and provide various other documents

ultimately resulting in single applications filling multiple bankers

boxes. A cottage industry has sprung up for lawyers and consultants

assisting with applications.

“It’s

kind of putting marijuana on the same playing field as plutonium,” said

Chris Lindsey, legislative analyst of the national Marijuana Policy

Project, which favors legal regulation of marijuana sales similar to

selling alcohol. “It’s pretty phenomenal how high the bar is” to even

apply for a license.

The

patient ailments eligible for medical marijuana under the Illinois law

include: cancer, HIV, lupus, muscular dystrophy, severe fibromyalgia and

about 30 other diseases. Medical marijuana is typically used to treat

pain, nausea and other symptoms associated with these diseases.

It

does not include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), chronic pain or

other common ailments that are covered under other states’ medical

marijuana laws. The Illinois law includes a process allowing people to

petition to add new ailments to the list. Patients can get 2.5 ounces of

marijuana every two weeks, or more with a special waiver.

The

marijuana cultivation centers will be high-tech industrial indoor

agricultural facilities, typically covering 20 acres or more, with

complicated ventilation, lighting and watering systems. The law requires

security to be tight, with video surveillance, ID cards for entry and

“perimeter intrusion detection systems.”

The

dispensaries will essentially be retail outlets, likely located in

storefronts in commercial areas. However no walk-in buyers will be

allowed; patients must be registered with one specific dispensary.

The

Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation will

regulate dispensaries and the Illinois Department of Agriculture will

regulate cultivation centers, while the state Department of Public

Health handles patient registration.

The

departments are all part of the state’s Medical Cannabis Pilot Program,

a new entity within the state government which brings together

employees of the public health, agriculture and finance and professional

regulation departments along with 40 new employees, said Melaney

Arnold, a health department spokesperson who is also spokesperson for

the pilot program.

Illinois: A bad trip?

Some

applicants are wary of doing business in Chicago and Illinois, which

has a rich history of doling out sweetheart government contracts,

ranging from driving trucks, cleaning city buildings or construction

work, to vendors and suppliers with political connections.

For

years, Dick Simpson and colleagues at the University of Illinois at

Chicago have produced regular reports outlining years of Chicago and

suburban corruption and suspect business practices.

Simpson said this is a valid concern in the medical marijuana process.

“It’s

always a problem with contracts that are very profitable,” said

Simpson, a political science professor and former Chicago alderman.

“It’s even more tempting when it’s something at the margins of legality –

for instance Al Capone in the Prohibition era, or gambling or [horse]

racing. Every time gambling has been brought to the state it’s been a

concern, and medical marijuana has the same potential…[With fears] that

it would end up on the street or be very lucrative and bribes would be

paid to get the (licenses).”

Still, Linn and other lawyers and policy experts say they expect a rigorous and fair process.

“The

officials in the state who are making these decisions realize there are

many, many eyes on them,” said Brendan Shiller, an attorney representing several

applicants. “If it’s not very clear, very obvious that the best

applicants got chosen, then there will be all sorts of problems they

don’t want to deal with.”

State

lawmakers recognized that influence peddling would be a concern so

dispensaries and cultivation centers or political action committees

formed by them are prohibited from making political donations.

Dispensary

and cultivation center applications will be reviewed by committees of

about a dozen people, each from the finance and agriculture departments,

according to the state.

Committee

members have “policy, program and legal expertise, as well as

horticulture expertise for cultivation center panelists,” Arnold said.

The

selection committees will review applications with names and

identifying information redacted. However, some question whether

redaction could be done imperfectly, intentionally or not, and whether

letters of support or other supplementary materials will reveal

applicants’ identities.

Security

plans account for 20 percent of the decision in both categories. The

cultivation plan counts for 30 percent for centers, with other

categories including business plan and “suitability.”

“Bonus

points” are awarded for women and minority-owned businesses and for

plans to give back to the community, for example with educational

outreach, donations to HIV services or job training for veterans.

The

applications are not public or subject to the Freedom of Information

Act (FOIA), a provision lawyers and advocates say is necessary since

they include personal information like tax returns and competitive

business and security plans.

Arnold said officials are figuring out what if any documents from the decision-making process will be subject to FOIA.

While the Quinn Administration is on board with keeping applicants’ names confidential, Governor-elect Bruce Rauner is not.

“The

application process for medical marijuana should not be held in secret

where insiders win and taxpayers lose; it should be open and

transparent,” Rauner said in a campaign press release. Rauner also

called for passage of a new law making changes to the application

process.

Lawyers argue

their clients involved in other industry sectors fear reputational harm

if it’s known they are interested in medical marijuana.

Proposals

for dispensaries and cultivation centers have also drawn opposition in

communities where they are proposed, with some neighbors associating

them with crime or debauchery, a connotation many business leaders want

to avoid.

When

licenses are awarded it is likely the recipients’ identities will all

become public, but there is no point in revealing the identities of

people who never get licenses, attorneys argue.

“It’s

typical to see a business or investment fail, that’s nothing new,” said

attorney Vallerius. “But it’s different when you go to church and

everybody keeps staring at you because they heard you grow and smoke

drugs.”

So far, the identities of

some dispensary and cultivation center applicants has become public

primarily through filings for the special use permits required from

municipalities, which can be obtained before or after a state license is

issued.

In Chicago,

City Council decides on the special use permit. This summer City Council

passed legislation allowing dispensaries in business and commercial

districts as long as they are 1,000 feet from schools and not in

residential areas.

Walter

Burnett Jr. is alderman of the 27 th ward where both GTI and Mandera

want to open dispensaries. Burnett told DNAInfo that he fears “yuppie

wards” will get all the dispensaries. (Burnett did not respond to

requests for comment.)

The

dispensary licenses will be awarded in “townships” geographically

spread across the city. The South Township drew no applications, while

the West Township had 10.

Rules, regs abound

The awarding of licenses is only the start of a raft of new responsibilities for a stressed state government.

The

state needs to select labs to test the marijuana being produced, and

carry out strict oversight of the cultivation and dispensing processes.

Licenses are renewed annually, after reviews by the state.

Operators

are required to carefully log and account for all the marijuana

produced. It must be packaged at cultivation centers and sold by

dispensaries unopened – no jars of loose product to sample or bundle

on-site.

Unsold marijuana must be destroyed and transported to landfills in a regulated process, with state police notified.

The

law includes provisions meant to prevent monopolies and keep prices

fair. One party can have an interest in only three cultivation centers

and five dispensaries statewide.

And

cultivation centers must offer the same prices to all dispensaries. But

some are concerned patients and independent businesspeople will still

be taken advantage of by big conglomerates.

“If

everybody who has a cultivation center has a dispensary or vice versa,

there’s not going to be a whole lot of competition,” said Shiller.

“People will just sell to themselves – that may be problematic.”

Tammy

Jacobi owns Good Intentions LLC, a clinic in West Town that advises

patients on how to register for the program and connects them with

doctors.

Jacobi said

she sees much potential for market manipulation under the rules. She

thinks cultivation centers will find a way to offer favorable prices to

dispensaries they also own, perhaps by selling different types of

products to different dispensaries. And she fears dispensaries could

band together to agree on prices higher than patients should have to

pay.

She points to a

law proposed in Michigan that could allow medical marijuana sales to

Illinois patients, potentially competing with Illinois dispensaries.

Meanwhile

experts note that if Illinois dispensary prices are higher than street

prices, many consumers will still go the illegal route.

Lang said that any such problems will become apparent as the pilot program plays out, and can be addressed in a new law.

“I

actually think these guys will not make as much money as they think

they will, certainly not now. When we refine this, when the model

program sunsets and we make a new law, there may be better opportunities

for businesses and better prices for patients.

“We’ll

have a better grip on what it means and how to make it work for really

sick people and how to enhance the revenue for the state of Illinois,”

Lang said.

Kari

Lydersen is a Chicago-based author and freelance writer who regularly

reports on government for the Better Government Association and other

media outlets.