Political mudslinging in Springfield

Back then it was worse

HISTORY | Erika Holst

After enduring the barrage of political ads spewed forth during the recently concluded election campaign, one starts to wonder if the tone of the political debate could sink any lower, and if candidates could attack their opponents any more viciously. The answer, surprisingly, is yes. We’ve actually come a long way since the early days of Illinois’ statehood. Elections of the early 19 th century inspired political brawls that make today’s contests look like sandbox fights. Read on for two examples of antebellum politicians who considered colorful name-calling and physical attacks perfectly reasonable ways of confronting their opponents.

“Spindle-shanked, toad-eating man-granny”: The Congressional Election of 1834 In 1834 William L. May and Benjamin Mills were vying to represent the largest congressional district in Illinois, which stretched from Springfield north to the border of Wisconsin, covering nearly half the state. Both men were Democrats, both were lawyers, both were supporters of Jackson, and both had traveled around the district together, campaigning more or less amiably until one of Mills’ supporters published a letter in the Sangamo Journal which raised some unsavory questions about May’s past.

Chief among them was the rumor that May had been indicted by a grand jury for breaking into a house some years back. May paid advertising rates to purchase space in the newspaper so that he could refute the charge. Protesting that he was no common burglar, May published a letter from a friend, who loyally testified that, so far as he could tell, “your entry into the dwelling house was not to commit murder, but to have illicit intercourse with a female then residing there.”

It wasn’t a great defense, and May’s opponents pounced on it. A letter signed “Agricola” was published pointing out that May’s sole defense to the burglary charge essentially said “I did break into the dwelling house of my friend in the night time, not to commit a felony... but only, my dear constituents, only to commit adultery with my friend’s wife.” Agricola questioned whether May was fit to represent the Third Congressional District of Illinois.

Apparently unable to deny

the charge, May went on the offensive. “Who is this ‘Agricola?’” he

demanded in another newspaper response. “Some puling, sentimental, he old

maid! Whose cold liver and pulseless heart, never felt a desire which

could be exempted, except for getting money… some spindle-shanked,

toadeating, man-granny, who feeds the depraved appetites of his patrons

with gossip and slander… who being deprived of their virility endeavor

to compensate themselves by the enjoyments of mischief-making.”

Apparently

the one thing Illinois voters liked less than an adulterer was a

mangranny. A few weeks later May was elected to Congress by a

comfortable majority.

Springfield Scuffle: The Congressional Election of 1838

In

the summer of 1838, John T. Stuart and Stephen A. Douglas were rivals

for the same seat in Congress that William L. May had won four years

earlier. They had been traveling together across the huge district,

which encompassed 22 counties from Springfield to Chicago, campaigning

and debating, rivals on the stump by day, bedfellows at night in the

rustic country accommodations.

Personally,

they probably got on well enough at the start of things. But even the

most congenial of traveling companions will start to grate on each

other’s nerves during the long course of a campaign. By June the Sangamo Journal was

reporting that “It is said that Mr. Douglas’ affection for Mr. Stuart

is not reciprocated and that Mr. S. has gone south, and will travel no

more in his company.”

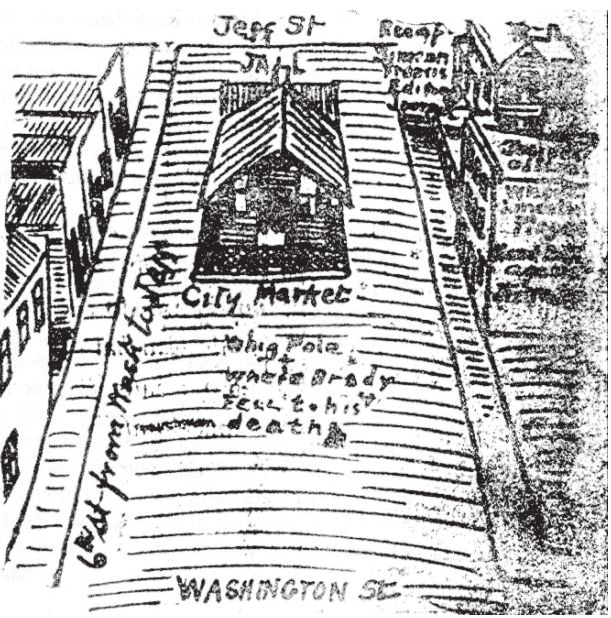

Tensions

between Douglas and Stuart came to a head shortly before the election

at a joint debate in front of the old market house at the corner of

Sixth and Jefferson Streets in Springfield. As Douglas was railing

against Stuart’s character, something inside Stuart snapped. Jumping up

from his seat, Stuart charged forward and seized his small opponent

around the neck. Douglas was small but scrappy, and no doubt put up an

admirable fight. Stuart, however, had the advantage of being taller and

heavier. Not content with a mere headlock, Stuart picked Douglas up and

carried him about the market house lawn, while Douglas, sputtering and

shouting in protest, flailed desperately in an attempt to free himself.

The crowd hooted and hollered to see the Little Giant carried about like

a sack of potatoes, red-faced and shouting. Douglas, for his part, did

the only reasonable thing a small man in a tough situation could do: bit

Stuart’s thumb as hard as he could. It wasn’t a roundhouse punch, but

it did the job, and Stuart dropped him to the ground. Stuart went on to

win the election by the very narrowest of margins: a bare 12 votes, out

of more than 36,000 cast. When he took his seat in Congress at the next

session, his fellow Whigs gave him a standing ovation in salute of his

hard-won victory. He carried a scar on his thumb until the day he died

as a souvenir of the time he had bested the Little Giant.

Erika Holst is Curator of Collections at the Springfield Art Association and the author of Wicked Springfield: Crime, Corruption, and Scandal During the Lincoln Era.