Civil war

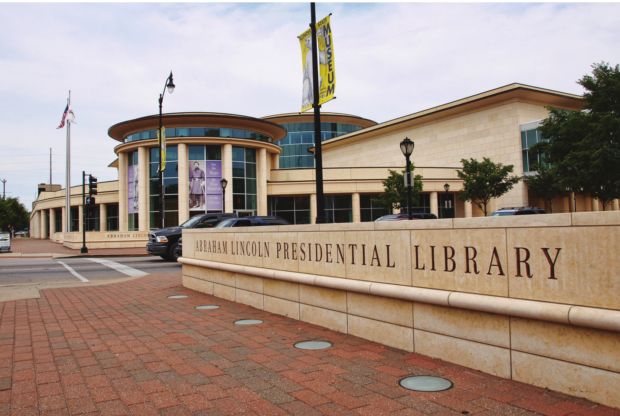

Fight continues over ALPLM

MUSEUMS | Bruce Rushton

Dysfunction and acrimony were on full display last week as state lawmakers in Chicago discussed the future of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

Officials charged with running the museum threw brickbats at each other during the hearing of the House State Government Administration Committee. ALPLM executive director Eileen Mackevich told lawmakers that she isn’t allowed to make decisions about hiring or spending. She said that she had no meaningful role in hiring either the institution’s chief of staff or deputy director.

“Why do we need you?” asked Rep. Jack Franks, D-Woodstock, chairman of the committee.

“I’m redundant,” admitted Mackevich, who described Amy Martin, head of the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency that is the institution’s umbrella agency, as her de facto boss. “I don’t have the power to envision the whole as I once did.”

Martin, whose agency is also charged with administering historic sites such as the Lincoln Tomb and the Dana-Thomas House, said that she spends 80 percent of her time on ALPLM issues. Without mentioning names, she suggested that a degree in library services and experience running an institution the size of the presidential library museum should be a requirement for the executive director’s post. Mackevich has no such degree, nor had she run a museum before she was hired in 2010.

“It appears to be a dueling directors problem,” observed Steven Beckett, a University of Illinois law professor who touched off an uproar last spring by drafting legislation that would put control of the institution under an ALPLM advisory board that he heads.

At least one lawmaker wasn’t impressed. “I’m still not sure what the actual problems are here,” complained Rep. John Cabello, R-Loves Park, at the end of the hearing that ran more than three hours. “This is ridiculous. It sounds like a bunch of kids who can’t get along. We’re wasting tax dollars just having this meeting.”

Amid the bickering lies a financially strapped institution rocked by a power struggle between Beckett’s advisory committee and the IHPA board of trustees, which sets policy and controls the budget.

When it opened 10 years ago, the institution was expected to eventually have 143 employees, Beckett said, but the staff now stands at less than half that, with no significant increases planned. The institution only recently hired an education director, a key job that has been vacant for more than a year, but there is no exhibits director. There hasn’t been a state historian since 2011, when Thomas Schwartz left to become the executive director of the Herbert Hoover Presidential Library and Museum in Iowa. Mackevich told lawmakers that the library, which once had five cataloguers to organize and index research materials, is down to one. Management ranks are so thin, she said, that all 18 employees in the library report directly to the library director, who is overwhelmed.

“I met with staff last week,” Beckett told the committee. “The staff basically feels that people aren’t paying attention. They say they feel unappreciated.”

The museum and library operate under an awkward governance structure that puts ALPLM under IHPA, but doesn’t give the agency director or IHPA trustees the power to hire or fire the institution’s executive director. That power lies with Gov. Pat Quinn, who has remained neutral on governance questions. The House last spring passed a bill that would transfer control of the institution to Beckett’s advisory committee, but the plan stalled in the Senate, and it isn’t clear what, if any, action lawmakers might take. Suggestions have included turning the ALPLM over to a university or the national archives, but Martin discouraged both ideas.

Universities, Martin said, have financial problems of their own. She said that the IHPA has contacted the national archives about taking over the institution, but federal officials weren’t enthusiastic.

“We have reached out to the national archives, and they’re not interested in pursuing it given the current financial arrangements,” Martin said. “The state would be giving away an institution that cost $150 million to build and $100 million to run over the last 10 years. Do we really want to give away a $250 million investment and all of the state’s historical records?” On the other hand, revenue from the museum isn’t nearly sufficient to cover costs. Fundraising has suffered since the governance spat erupted last spring, according to Wayne Whalen, chairman of the board of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library Foundation board, a private nonprofit formed to raise money for acquisitions and other expenses. The foundation raised nearly $4.8 million last year and has taken in $3.1 million this year, Whalen told lawmakers, with past donors either not returning calls or saying they’re reluctant to make donations given dissension about the institution’s leadership and direction.

The foundation is deeply in debt due to the acquisition of a collection of Lincoln artifacts known as the Taper Collection for $23 million in 2007. The foundation still owes $11 million and is paying $500,000 a year in interest and an equal amount to pay down the principal, Whalen and Carla Knorowski, the foundation’s executive director, told lawmakers. The foundation has eight full-time employees, one part-time employee and annual operating expenses of $1.7 million, Knorowski told the committee.

“Isn’t that a high administrative cost?” asked Rep. Robert Pritchard, R-Sycamore.

“I don’t think so,” responded Knorowski, who was paid $250,000 for the fiscal year ending in June, 2013, more than Mackevich, Martin or anyone else associated with the institution. “We are rather lean when it comes to expenses. It’s simply what it costs to raise money.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].