Black and white

Police say they’re trying to make the city safer. But black drivers feel targeted.

RACE | Patrick Yeagle

Just before midnight on Nov. 4, Samuel Johnson of Springfield was returning home from Bloomington when he saw a police cruiser in the median along Interstate 55. He hadn’t been drinking or using drugs, and he had nothing illegal in the car, but he still thought it best to play it safe. When you’re a young black man with a passion for social justice, you learn that kind of thing quickly.

Johnson kept his speed under the limit and signaled his turn off of the highway at Clear Lake Avenue. In his rearview mirror, however, he saw the cruiser catching up to him on the off ramp.

Heading west on Clear Lake, Johnson saw another cruiser parked at the BP gas station. He signaled his lane change from right to left as he approached Dirksen Parkway, but just as he passed through the intersection, the red and blue lights began flashing. He ended up in the back of the squad car, with a traffic ticket and a mission.

Johnson’s ticket and his arrest were thrown out on July 30 when both sides agreed that Johnson hadn’t actually committed a traffic violation, so he shouldn’t have been pulled over in the first place. But the case is more than a simple question about how to use a turn signal; Johnson believes his stop was an example of racial profiling, and he’s now considering a federal civil rights lawsuit which, if successful, could set an important legal precedent about how police use their power to stop and detain drivers.

The perfect “pretextual” stop case Racial profiling is the controversial notion that law enforcement officers stop, detain, search and otherwise treat people of certain races, ethnicities or skin colors differently than they do white people. It’s related to the concept of a “pretextual stop,” in which a law enforcement officer pulls over a driver for a minor traffic violation like a missed turn signal or broken taillight as a pretext to look for illicit drugs, unlicensed weapons or other illegal activity. The two concepts tend to blend together because many pretextual stops occur in areas with predominantly nonwhite populations.

Johnson believes the officers who pulled him over followed him after seeing his vehicle and his skin color in their headlights as he passed their highway perch. The dash camera video from the cruiser shows the cop car aggressively cornering on the ramp as it rapidly gains on Johnson’s car, even before he changed lanes and incurred the turn signal charge.

The officers wrote in their police report that the criminal database showed five priordrug arrests on Johnson’s record. Johnson says he has only been arrested once for drugs, in 2001, but those charges were dropped. The criminal database is not available to the public, so it’s not possible to know whose version is correct. However, Johnson has no prior criminal cases on record in the Sangamon County Circuit Court or the McLean County Circuit Court, which includes Bloomington.

Had there been five prior drug arrests on Johnson’s record, it would explain why the officers suspected him of illegal activity and asked him to exit his vehicle to sign the citation. Believing he had done nothing wrong, Johnson refused to get out of the car, and the officers placed him under arrest, which he didn’t resist.

Most pretextual stop cases feature less than sympathetic defendants. In the main controlling case on pretextual stops, Whren v. United States (1996), the defendant in Washington, D.C., was caught with two bags of crack cocaine after failing to signal a turn. Whren had been driving and noticed a police car turn around behind him, which prompted him to speed away. In court, he argued that the drug evidence should have been thrown out because the officers stopped him only to look for drugs, but the U.S. Supreme Court held that any traffic stop – pretextual or otherwise – is legal if there is justification for the stop. While stopping someone on a mere suspicion of illegal activity would be an unconstitutional violation of the Fourth Amendment prohibition on unreasonable searches, police have the discretion to stop someone for a legitimate traffic violation, the court said.

Johnson’s case is quite different from Whren, however. Not only was Johnson not drinking, doing drugs or carrying anything illegal in the car, but he didn’t even violate the rules of the road. The officers who pulled him over said he failed to signal his lane change for 100 feet. Johnson’s attorney, Peter Wise of Springfield, successfully had the case thrown out because state law actually has no provision for how long a turn signal should be used before a lane change. The part of the statute that mandates signaling for 100 feet refers instead to turning.

“It was a mistake of law on the part of the officers,” Wise said. “I have seen that to be the basis of what I have believed to be pretextual stops, and that’s a pretty ticky-tack basis for stopping someone.”

Wise, who has practiced law for about 30 years, says pretextual stops typically happen when a law enforcement agency has been investigating a particular individual and suspect a traffic stop might yield evidence of

illegal activity. He says it’s usually very difficult to prove that an

officer only stopped a vehicle in order to search it because the courts

have held that, as Wise puts it, “an officer’s subjective intent in

making a stop is not a factor” that a court considers when deciding

whether a stop is legal. Because Johnson’s case doesn’t involve a legal

stop, the officer’s intent could become a factor if a lawsuit is filed.

Driving

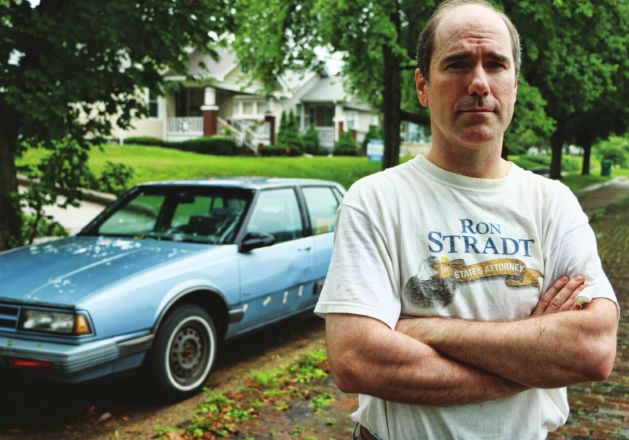

a stereotype Eric Fisher of Springfield says he, too, is often pulled

over for “driving while black.” Fisher, who is white, enjoys driving

older cars like his 1977 Oldsmobile Cutlass. He says he typically gets

pulled over in that vehicle about once per year.

One

late evening in November 2013, shortly after Johnson’s stop, Fisher was

driving his dented, circa-1990s Oldsmobile 88 sedan when he was pulled

over for failure to use a turn signal at the intersection of North Grand

Avenue and Ninth Street. Fisher admits that he isn’t sure whether he

used his signal; he says he does so instinctively.

“What

surprised me was that he issued me a citation. Usually they just give

me a warning or send me on my way without any further ado, once they see

my papers are in order,” Fisher said, adding that he feels he was

pulled over because his vehicle was old.

“I

assume they were just trying to develop the probable cause they need to

search the car for drugs, given the stereotype of the older car being

driven by a racial or ethnic minority in possession of drugs,” he said.

Fisher

began collecting data on traffic stop cases from the Sangamon County

Circuit Clerk’s office. He found that in the year preceding his November

2013 stop, Springfield police had written 2,481 tickets for operating a

motor vehicle without insurance and 836 tickets for driving on a

suspended license. Meanwhile, improper turn signal usage was cited only

124 times.

“It now

makes sense that (driving without insurance or on a suspended license)

are really what the police are looking for, and simply work their way

down the list of predicate offenses until they find an excuse to pull

someone over and check driver’s license and proof of insurance,” Fisher

said. “My experience and Mr. Johnson’s experience ... indicate that the

police pick out the person they want to pull over, and then look for

excuses to do so.”

Despite all of that, Fisher praises the police for being polite and helpful any time he has needed them.

“I

am a citizen, however, and an American, and am offended by the idea

that an officer might pick out a person to check for driver’s license

and insurance based on a stereotype, and then work his way down the list

of possible offenses to ticket until he hits paydirt,” he said. “If I

don’t raise a stink, who will?”

Putting

the numbers in context Traffic stop data collected by police agencies

and analyzed by the Illinois Department of Transportation shows that

between 2004 and 2013, minority drivers were pulled over by Springfield

police more than twice as often as white drivers after accounting for

population size.

To

figure that out, IDOT divides the percentage of minority traffic stops

by the percentage of minority driving population. Springfield’s minority

driving population was about 20 percent of the total population in

2013, but minority drivers accounted for 42 percent of all traffic

stops. That yields a ratio of 2.05, meaning stops of minority drivers

were twice as frequent as their proportion of the population would

typically warrant. A ratio of 1.0 would mean minority drivers are pulled

over exactly in proportion to their share of the population.

Illinois Times further

analyzed the traffic stop data from 2004 to 2012 and found that areas

of Springfield with the highest percentages of black residents also had

the highest number of traffic stops. The analysis excludes several

hundred traffic stops in which the beat location data is missing or

corrupted, so numbers are approximate.

The

Springfield Police Department divides the city into eight “beats” for

patrol purposes. The 300 beat, which roughly covers the city’s east side

between Carpenter Street and South Grand Avenue, contains a population

of around 75 percent African-American residents. That beat also had the

highest number of traffic stops every year between 2004 and 2012. More

than 34,000 of the 188,625 traffic stops conducted by Springfield police

during that time happened in the 300 beat, about 18 percent.

The

second highest concentration of traffic stops occurred in the 400 beat,

which covers the city’s east side between South Grand Avenue and

Interstate 55. Parts of that area have up to 63 percent African-American

residents and saw more than 14 percent of all traffic stops between

2004 and 2012.

By

comparison, two beats on Springfield’s west side with large majority

white populations had far fewer stops. The 600 and 700 beats together

cover most of the city west of Chatham Road and south of Jefferson

Street, where census data show a typical white population of around 80

to 90 percent. Those two beats each saw slightly more than nine percent

of all traffic stops over the same time period.

Deputy

chief Dennis Arnold of the Springfield Police Department acknowledges

that black drivers may feel targeted for traffic stops.

“I

understand that there’s a perception with some individuals in the

community that we base our traffic enforcement on an individual’s race,”

Arnold said. “I’m here to tell you that’s absolutely false. We do not

base our enforcement efforts off of an individual’s race.”

Arnold

says the IDOT traffic stop numbers alone are misleading. To put them in

context, Arnold looked at the number of calls police fielded from each

beat over the past five years. The 300 beat on the city’s east side,

which had the highest percentage of traffic stops at 18 percent, also

had the most calls to police. Of the 583,147 calls to police from all

over the city during that period, beat 300 produced 91,983 calls, or

about 15 percent of the total. That’s the highest proportion of calls

for any beat, and it’s almost double the 47,054 calls that came from the

majority-white, west side 700 beat.

While

those calls include everything from gunshots fired to domestic

disturbances, Arnold says they provide the department with an important

picture of where the most manpower needs to be concentrated. In short,

areas that produce the most calls to police receive the most police

patrols in response. It naturally follows, Arnold says, that a stronger

police presence in predominantly black areas leads to more police

encounters with black drivers.

However,

the east side 400 beat, with the second-highest percentage of traffic

stops, ranked fifth among the eight beats in terms of calls to police.

Besides the first-ranked 300 beat, the downtown 200 beat, the north side

100 beat surrounding Grandview and the enormous 500 beat stretching

from south of downtown to Lake Springfield all had higher numbers of

calls to police than the 400 beat. Arnold explains the anomaly by

pointing out that although the 400 beat ranked fifth in overall calls,

it was second for calls regarding drugs and violent crime.

Arnold

also says the department has taken a “proactive approach” to stopping

drug trafficking on interstates 55 and 72, which he says are major

thoroughfares for drugs to enter Springfield from St. Louis, Chicago and

elsewhere. Springfield police regularly patrol the highways, Arnold

says, adding that the highways are within their jurisdiction.

Johnson,

the black man stopped in November, says Arnold’s explanation of more

patrols leading to more stops makes sense, and he agrees that’s probably

why the number of traffic stops is proportionally higher for black

drivers than for white drivers. However, he questions whether increasing

patrols in response to crime is the answer. Instead, he points to the

larger social ills of poverty, lack of education and lack of employment

in black communities as the real drivers of crime, so concentrating on

police patrols instead of helpful programs makes the problem worse.

“We’re already mad. We’re already angry.

We’re

already starving. We’re already struggling,” Johnson said. “And then

you’re sending more police over, so all you’re doing is enhancing my

anger to where I’m liable to go do more violence. Now, if you bring me

more things I can eat or you bring me a job, or you’re bringing me an

education, you’re lifting me up instead of bringing me down.”

Johnson describes growing up black as “always having a sense of paranoia.”

“Every

time you pass a cop car, you’re always looking out your rearview

mirror,” he said. “You don’t know if they’re going to pull you over, not

because you have something on you or you’re doing something illegal,

but because growing up, that’s what we’ve seen, and that’s what was

happening to us.”

He

says that paranoia creates a feeling of inequality, which is compounded

by seeing a traffic courtroom full of people who already live in poverty

paying hundreds of dollars in fines and court fees for minor traffic

violations.

“You feel

like there’s no hope, and it’s mentally damaging,” he said. “You carry

that every day. Even now, if I see a cop, I look in the mirror. I hate

it, but I do. I see my peers and other people in my culture do the same

thing.”

Arnold, the

deputy police chief, says traffic stops are an important tool for police

to patrol a neighborhood, and his fellow officers are simply trying to

do their best to make the city safer.

“Nobody

in this community wants illegal guns, drugs or violent crime in their

neighborhood,” he said. “East side citizens are no different than anyone

else in the city; they don’t want it in their neighborhoods. We’re

doing what we can to address that. Are some innocent people going to get

stopped? Yes, that’s going to happen. But our officers are out there

doing their job, attempting to get drugs and illegal guns off the

street. It’s not easy.”

Johnson

says he harbors no anger at the police, and if he does file the

lawsuit, it won’t be about money, but about making a statement. He also

urges others not to simply take whatever plea bargain they’re offered in

traffic court.

“I

would like for everyone to take this whole dialogue as educational and

apply it,” he said. “Don’t just give in on a traffic case if you know

that you’re innocent. Don’t just do what we’ve always been doing – not

just black citizens, but all citizens. Go all the way, and don’t settle

on what you’ve been conditioned to settle for. Look further; expand your

knowledge. We have to do this for our kids at the end of the day,

because if we don’t do it, our kids are going to do the same thing.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].