In central Illinois, VA means delay

The national scandal hits home. An underfunded overworked health care system needs reform.

HEALTH CARE | Zach Baliva

The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs scandal is starting to hit closer to home. It was late 2013 when Dr. Sam Foote filed a complaint with the VA Office of Inspector General and met with newspaper reporters alleging that patients died waiting for treatment at the Phoenix VA. VA staffers, Foote says, falsified records to meet internal standards. Early this month, U.S. Secretary of Veterans Affairs Eric Shinseki ordered audits of every VA facility in the nation. Recent reports from The American Legion claim that investigations are underway in as many as 19 states – including Illinois. U.S. Senator Mark Kirk has called for the resignation of Joan Ricard, director of the suburban Chicago Edward Hines, Jr. VA Hospital, after a social worker claimed administrators there cooked the books to obtain performance bonuses.

In central Illinois, 150,000 veterans have access to only a few medical facilities spread out over a 34-county area that includes part of Indiana. The nearest hospital is in Danville – 127 miles from Springfield. Veterans who need medical care unavailable at their local clinic are asked to travel to the nearest facility where those services are provided – even if that facility is outside of the Illiana Health Care System. Not all clinics are created equal; some are larger and offer more specialized treatments. Live in Springfield but need glasses or an X-ray? You’re going to Peoria. Springfield veterans are often required to travel as far as St. Louis, Danville or Indianapolis. Travel reimbursement – 41.5 cents per mile, or about $100 for a round-trip drive to Danville – is usually available.

Ed Boblitt of Auburn has the system’s geography memorized. That’s because he’s often sent to Peoria, Danville, Decatur and other facilities. He’s grown accustomed to waiting weeks and even months for an appointment. The long waits, he says, have exacerbated a skin condition and even cost him sight in one eye.

There are plentiful stories of central Illinois veterans enduring long waits and long drives for access to free health care. They include a Jacksonville veteran who was denied local chemotherapy, a one-eyed man who drives to St. Louis for prosthesis, and a veteran who claims the VA has no idea which branch of the armed forces he served in.

The Springfield outpatient clinic at 5850 South Sixth Street is open during regular business hours and provides primary care, mental health care, social work and blood drawing services. Dr. Dexter Hazlewood of Peoria oversees the clinic and others in Decatur, Mattoon, Peoria and West Lafayette, Indiana. The clinics, anchored by the Danville hospital, comprise The Illiana Health Care System. Hazlewood says an eligible veteran makes an appointment by calling a scheduling center. Triage nurses “make appropriate inquiries and decide the appropriate response.” If they decide a veteran needs to be seen, they attempt to book an appointment “within 14 days of a desired date.”

Scheduling complexities and travel requirements often seem burdensome to central Illinois veterans. In recent years, the VA started providing shuttle service. The shuttle departs the Springfield clinic every morning at 9:30 a.m. and goes to Danville before continuing on to Indiana and then making the return trip (which departs from Danville at 4:30 p.m.). If the shuttle is on time, veterans who departed Springfield at 9:30 a.m. will return at 6:30 p.m. A brochure, however, advises veterans to expect delays, stating that “evening shuttles departing from Danville…may be delayed waiting for the Indianapolis shuttle to return to Danville.”

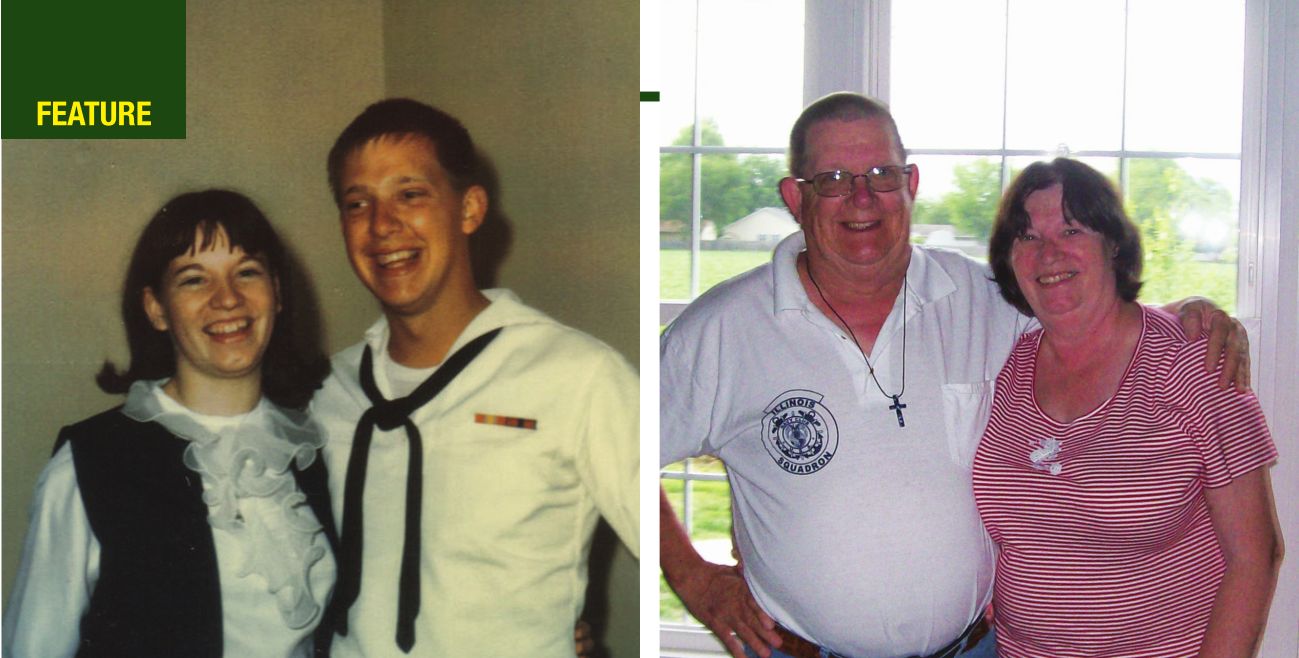

Springfield resident Jack Jackson served in the United States Navy from 1964 to 1968. He lost an eye in a service-connected incident and now wears a prosthetic. Every two years, Jackson travels to a VA facility in St. Louis for routine prosthetics appointments. “Sometimes it can take four months before you are seen by the doctor,” says Jackson. He’s avoided the wait time – longer in the summer – by driving in the winter, but says a 210-mile round-trip drive twice in seven days (once for the required follow-up appointment) is too difficult with just one eye. Jackson, however, has maintained his humor about it all. Area residents may remember him as longtime host of WMAY’s the One-Eyed Jack show.

Today Jackson, 68, owns and operates the Dr. of BBQ food stand on the corner of Fifth and Stanford in Springfield. While limited access to care can be frustrating, he gives the VA high marks for quality. Jackson lived for several years with acute foot pain that never went away despite regular visits to a Springfield doctor, which Jackson financed personally. When that doctor died, Jackson finally gave in and drove himself to Danville for an appointment where a VA doctor fixed the chronic problem in one short appointment.

Living with a system that forces you to rely on a small local clinic or drive hundreds of miles simply changes the way veterans make their medical decisions. Although the VA claims its maximum wait time is 14 days, most veterans say it can take up to three months – especially if they’re unable to convince the triage nurse that their needs warrant an immediate appointment. “If I have a severe cold, I know I’ m probably not going to get in to see a doctor before my cold has run its course,” Jackson says. “I’ll try to pump myself full of OTC meds or find someone with leftover medication that I can borrow.”

Those with acute problems face even more difficult dilemmas. A veteran who experiences serious abdominal pain on a Sunday morning, for example, can either wait for the clinic to open on Monday, drive himself to Danville, or visit a local hospital Emergency Room and hope the VA picks up the tab. Illiana Health Care System director and CEO Japhet Rivera, who works out of the medical center in Danville, says the VA pays for veterans’ stays in the ER. “If they are eligible there should

not be a problem,” he explains, while also acknowledging that there are

sometimes “judgment situations” in which the veteran and the VA disagree

about the necessity of the ER visit. The judgment call debate gets

especially cloudy in light of reports that veterans in some states are

resorting to the ER when standard appointments aren’t available.

Michael

Leathers, spokesperson for Springfield’s Memorial Medical Center says

his hospital sends the veteran a billing statement but works with the VA

office to resolve the claim. A veteran sometimes receives a bill

because the VA has determined a portion of the claim should be

“self-pay.” Veterans who meet the guidelines, Leathers says, can also

receive assistance through Memorial’s charity-care program, which may

include a write-off of all or part of their balance due. Linda Teeter,

manager of managed care for Hospital Sisters Health System (St. John’s)

in Springfield says she’s also seen cases in which veterans receive at

least part of an ER bill.

The

national outcry over the VA has revolved around long delays and

improper actions to make those delays appear less severe. But even when

the system works, questions remain: Is the VA requiring too much of

rural veterans who need routine medical services? Are travel

requirements fair? Are there alternatives? Jackson believes each veteran

should receive a photo ID entitling him to free medical care at any

public or private facility nationwide. Pilot programs and other

initiatives have explored similar strategies to varying levels of

success, and in critical situations the VA will allow veterans to

receive local “non-VA” care from outside providers.

Congresswoman

Tammy Duckworth, D-Schaumburg, served as director of the Illinois

Department of Veterans Affairs from 2006 to 2009. She says she wants

“veterans to access the highest level of health care as quickly and as

efficiently as possible, regardless of where they live.” A longtime

supporter of VA’s expansion of services to veterans in all areas,

Duckworth is “exploring options that allow veterans to access local

health providers if the care is appropriate and VA services are not

available.”

While the

VA sometimes allows veterans to seek outside medical care, there are no

rules or guidelines to determine a veteran’s eligibility for non-VA

treatment. Director Rivera says the VA “decides on a one-by-one basis,”

and tries to “avoid people, especially the elderly, traveling long

distances.” When asked what age or distance makes a veteran eligible to

receive Males:

677,072 Female: 67,638 care outside of the VA system, he says, “We don’t

have any type of specific criteria, and in many cases we have to use

our judgment and common sense to make sure we are providing

compassionate care.”

Veteran population in Illinois

744,710

Males: 677,072 Female: 67,638

Clinic manager Dr.

Hazlewood says relying on outside providers would ultimately be detrimental.

“Everyone

feels like they have a good reason [to receive outside care], but if we

were to do that across the board, it would sink the system,” he

explains. Veterans like Jackson disagree, wondering why the VA can

reimburse about $100 for travel fees but not use the same amount of

money to pay for negotiated group rates through local health care

providers.

Jacksonville

resident Steve Bartlett served in the United States Marine Corps from

1983 to 1987 and was a mechanic in the United States Army from 1993 to

1996. Many years after his discharge from the Army, doctors told him he

developed Non-Hodgkin lymphoma, a cancer of the lymph tissue that can

develop if a patient encounters certain chemicals like those Bartlett

may have contacted in water wells during his time in the Army. Two years

ago, Bartlett petitioned the VA for non-VA approval so he could receive

chemotherapy near his home. The VA denied his request, asking him to

drive 300 miles round-trip to Danville to receive radiation treatment

once every three weeks for two years. Bartlett, a prison guard who will

turn 50 in August, paid out of his own pocket for local care and is now

cancer-free.

The

Veterans Health Administration traces its origins back to the Civil War

and federal facilities authorized by President Abraham Lincoln. Herbert

Hoover created the VA in 1930, and Ronald Reagan renamed the agency as

the Department of Veterans Affairs in 1989. Until the 1990s, veterans

were required to access care at a VA hospital. In 1997, the department

started enrolling almost all veterans into the VA and standardized

eligibility criteria. They established a network of community-based

clinics to improve rural access. Since 1998, most vets – not just those

with service-connected disabilities – have been eligible for free

medical care. There are still income and discharge requirements, but the

change in the 1990s dramatically increased the number of patients who

have access to free medical care through the VA. The increase also made

delays inevitable.

The VA is the second largest bureaucracy in the federal government, behind the Department of Defense. President

Obama’s 2015 budget includes $163.9 billion for the VA, and 35.4 percent

of that total is tagged for medical programs. Finances are tight,

demand is up, two wars are ending, and veterans are coming home in

record numbers. The Phoenix VA Health Care System – the one in the eye

of the waitlist storm – serves more than 80,000 patients with a budget

of $438 million. The Illiana system serves about 33,000 veterans with

$175 million. There’s simply not enough money to go around. That

unavoidable fact leaves doctors and administrators like Rivera and

Hazlewood repeating sad variations of a standard refrain: “We want our

veterans to know that we’re trying to do the best we can with what we

have.”

One disabled

veteran from central Illinois who spoke under the condition of anonymity

says he often sees a different doctor at a different facility and is

constantly repeating his medical history and then receiving random

appointment times and inaccurate health care diagnoses. At one point,

upon requesting his medical file, he discovered that his records list a

serious disease that he’s never had and lists him in the wrong branch of

service. Once, at a VA clinic, he casually mentioned feeling slightly

depressed. Two weeks later, a strong anti-depressant – usually

administered under careful supervision – arrived via United States

Postal Service. The veteran says he often has appointments scheduled for

him on days in which he is unavailable, has been sent notices for

appointments that were supposed to have already occurred, and has even

showed up for appointments in faraway cities only to be turned away

because staffers claim he didn’t actually have an appointment. He also

claims that triage nurses who schedule appointments over the phone have

refused to book appointments for things ranging from flu-like symptoms

to severe colds. Dr. Hazlewood says that should never happen. “You are

seen even if you disagree with the triage nurse,” he says. “Our care is

centered around the veteran. If a nurse refuses to make an appointment,

the veteran needs to file a complaint.”

Ed

Boblitt has so many afflictions he can’t even list them all. He served

from 1966 to 1975 in the United States Navy and the Air National Guard.

Now, he’s rated 90 percent disabled with a 10 percent unemployable

rating. He’s had serviceconnected heart attacks, diabetes and PTSD. “I

don’t even know what else,” he says. “I asked the VA for the whole list,

and they told me it would take two years to put together.”

VA

officials are promoting telemedicine to increase efficiencies and

decrease costs, but Boblitt says his first experience with the

technology has left him underwhelmed. Earlier this year, Boblitt

scratched a sore on his leg that became infected. Three weeks later, a

VA doctor examined his wound and provided medicine – but Boblitt was

allergic to it. He claims the medication “was eating the skin” off of

his leg. He called back for another appointment and was seen promptly.

Since the Springfield VA clinic doesn’t have a dermatologist, the

clinic’s medical staff photographed his wound and sent the images to a

doctor in Indianapolis. When that doctor couldn’t make a diagnosis, the

VA approved Boblitt for non-VA care. It took him two or three weeks to

receive the authorization in the mail. When he did, Boblitt saw a local

doctor who treated the wound immediately.

Boblitt

says he goes to Peoria every three months and occasionally drives to

Danville. He spent 120 days at the Phoenix VA hospital and another 45

days in a Des Moines facility. He’s learned he has to fight for every

aspect of his care. “Oh, they could do a lot better than they’re doing,”

he says. Even the little things are confusing. His medication –

received in the mail – changed from green and white to orange without

explanation.

Confusion

over pills isn’t his biggest complaint. “The VA blinded me in one eye,”

he says. Boblitt was hit by a car in his childhood and has experienced

deteriorating vision throughout his adult life. When a

doctor at the Danville hospital said he could help, Boblitt jumped at

the chance. He says the VA botched a cataract surgery in 2012 by failing

to notice a detached retina. Boblitt believes it may have been

partially detached due to previous trauma but became fully detached

during the procedure.

All

he knows is that after the procedure, he lost sight in the eye. “They

sent me to appointments in Peoria, Decatur and Springfield, but I had to

wait two weeks or more between each appointment,” he says.

“When

they finally got me to the right doctor who could reattach it, he told

me that it was too late.” That was four months after his initial

cataract surgery. Boblitt is now blind in one eye.

With

federal audits of all national VA health systems underway, Danville’s

Dr. Rivera is optimistic about the outcome and says his organization has

nothing to hide. Requests for complaint and disciplinary information

made under the Freedom of Information Act were not returned by Illinois Times’ print

deadline. Whatever the results, funding and awareness will remain key

issues. Rivera says that it’s often difficult to entice doctors to live

in Danville. The Illiana System employs about 65 doctors and 19 nurse

practitioners split between a hospital and five clinics. The average

salary for a primary care physician at VA’s Illiana Health Care System

is $116,000, excluding benefits like insurance and student loan

forgiveness. Forbes reports that in 2013, average pay for a

primary care doctor in the United States was $221,000. In the

Springfield area, the average is closer to $160,000.

Until

recently it was illegal for the VA to advertise its services, but with

advertising and outreach regulations changing, the agency is just now

learning how to coordinate marketing and outreach efforts. But could it

handle more patients? Currently, the Illiana system is treating roughly

25 percent of its eligible veterans. The national average is 30 percent.

The

state could increase the number of vets who get help – if it had money

to do so. Erica Borggren is the director of the Illinois State

Department of Veterans’ Affairs. IDVA is not part of the VA, but

augments federal programs and has Veteran Services Officers who assist

veterans in need of programs and benefits. Borggren and her staff employ

71 VSOs in 80 of 102 counties across the state, and those VSOs help

veterans access federal VA benefits. With hundreds of nonprofit

organizations offering to help veterans, accessing supplemental care can

seem overwhelming. That’s why the IDVA has created Illinois Joining

Forces (illinoisjoiningforces.org), a public/ private partnership that

creates a “no wrong door system” by providing information about numerous

benefits, services providers, and other resources in one location. Any

service member, veteran or family member can access the website and

search for help by type of need.

But

when it comes to providing good care to veterans, the main issue

Illinois faces is the budget, and how the state will grapple with the

$1.8 billion hole caused by the expiration of income tax rates. Agencies

are already preparing for dramatic cuts, and Borggren says IDVA is

expecting $17 million in cuts to its state funding plus the associated

federal resources. If the tax increase expires, as now appears likely,

Borggren expects to close half of IDVA’s veterans’ services offices, two

veteran homes and other critical services.

Ed

Boblitt served his country and is now unable to work. Jack Jackson

served in the military, lost an eye, and isn’t sure his bills will be

paid if he has a serious medical concern when the Springfield clinic is

closed. Steve Bartlett sacrificed for his nation and paid out of pocket

for his own cancer treatment. We owe these men and women better. It’s

time to reform the VA.

Zach Baliva is a filmmaker and journalist living in Chatham. [email protected].

For a map showing the distances to the central Illinois VA facilitires go to this story online at www.illinoistimes.com.