Fixing school funding

Illinois’ antiquated school aid formula doesn’t work

SCHOOLS | Lauren P. Duncan

Illinois has seen the price of food, gasoline, shelter and most basic necessities increase. Yet for four years the state hasn’t increased the amount it pays per child in public school. And the formula which determines how much state aid each school gets hasn’t been changed since 1997.

A few members of the General Assembly are trying to take steps to change the state’s antiquated school-funding system. In July, 2013, Sen. Andy Manar, D-Bunker Hill, a freshman lawmaker who had just taken office in January, was named as a co-chair of the Education Funding Advisory Committee (EFAC). Illinois Senate leaders formed the committee to address the state’s education funding disparities, including the fact that, at the time the committee was formed, about 67 percent of Illinois school districts reported deficit spending.

After the committee gathered testimony, on April 1 Manar introduced Amendment 1 to Senate Bill 16, or the Illinois School Funding Reform Act of 2014. It would set

up a formula to distribute education funding based on a local district’s “ability to pay,” which considers a district’s available local resources through property tax revenues. The formula also considers the poverty level of districts by factoring in low-income student populations. The bill aims to give property-poor districts a bigger slice of the state aid pie, and propertyrich districts a smaller piece of the pie. The proposal would also add greater weight to other special funding needs districts face, such as students with disabilities or gifted learners.

Presently, about 44 percent of the $4.3 billion in general state aid for education is distributed to districts based on their ability to pay. Manar’s bill aims to raise that number to about 92 percent so that most of the state’s funds would be distributed based on districts’ needs.

Manar said the proposal is a needed change toward reforming Illinois’ education funding.

“We need a comprehensive fix that deals with good policy and ignores the politics,” Manar said.

Illinois’ school funding formula is complex.

Entire college courses are taught on the funding system. Manar’s bill aims to change the method. The key point, Manar said, is to help address today’s education funding issues.

The state’s education funding problems mean some schools have had to close buildings, hold classes in windowless rooms and use outdated textbooks, Manar said at a press conference April 2 when he unveiled the bill. He said small towns are losing their identity, good teachers are losing their jobs and the achievement gap is rising in poverty-stricken districts.

“Those things are all a direct result of a law that today protects inequity.... We can do better in this state and this bill will get us there,” Manar said.

The problem

Illinois places a greater burden on local school

districts to fund education than most states. Article V of the Illinois Constitution says “the State has the primary responsibility for

financing the system of public education.” Yet the state government hasn’t taken that primary responsibility seriously.

The average state and local share of education cost in the United States is about 44 percent state share, and 44 percent local share, with the remaining cost paid with other grants or federal dollars, according to a report released April 7 by the Center for Tax and Budget Accountability (CTBA). In Illinois, the state carries about 28 percent of the bill, while local districts pay for 61 percent of the costs through property taxes.

The CTBA report states that over-relying on local property taxes to fund education is not good tax policy. Instead, CTBA emphasized that state-based revenue generated from income and sales taxes is a better way to tax people. “Illinois over-relies on property taxes because the state fails to pay its fair share of the cost of public education,” the report states.

Manar’s bill doesn’t change the sources of education funds in Illinois, though. It suggests the state move one step closer toward distributing funds based on districts’ needs with the revenues the state has.

Since

2010, Illinois has not increased the “foundation level,” which is the

amount the state has decided is needed to provide an adequate education

to children. The state share has remained at $6,119 per child. However,

many schools do not receive even that much, due to “proration,” or state

budget cuts. Yet the state’s Education Funding Advisory Board has

recommended that the foundation level be higher. In 2014, it said, the

minimum needed to adequately educate an Illinois student is $8,672.

What

the state pays to educate students may increase if Gov. Quinn’s plan to

increase education funding by $344 million next school year goes

through. However, agreement on a number of looming issues – including

extension of the temporary income tax and proposals for a progressive,

or “fair tax,” structure – stand between the governor’s proposed budget

and the fund increases becoming a reality.

Manar’s

bill aims to ensure that regardless of how much money the state

provides, the districts that need the money most will receive the most.

The

bill would reduce state aid to school districts that have more local

income and increase aid to districts that have lower local property tax

income, by taking into consideration local property wealth.

There

is a vast difference in property values amongst Illinois’ school

districts. Because districts receive most of their dollars from local

property tax revenues, this means propertyrich districts have the

opportunity to collect more money for schools. Wealthier districts tend

to have lower tax rates than poorer districts. For example, New Trier

Township High School District 203, which includes the suburban towns of

Winnetka and Northfield, has more than 10 times the local property

wealth of Springfield, yet Springfield’s tax rate is more than three

times higher. New Trier, however, is one of the state’s 72 “flat grant”

districts, which means

because its resources are so great, it receives a bare minimum of state

funds, $218 per student. Manar’s bill aims to decrease even the $218.

Even some of the wealthiest districts understand there needs to be a change in the funding system, Manar said.

“There’s

a realization that something has to change in our state system,” he

said. “If the state system crumbles, everybody is going to be affected.

Even the most wealthy … whether you spend $20,000 per student or $6,000

per student, the health of the state’s system is at stake here, and

that’s what we’re trying to talk about,” he said.

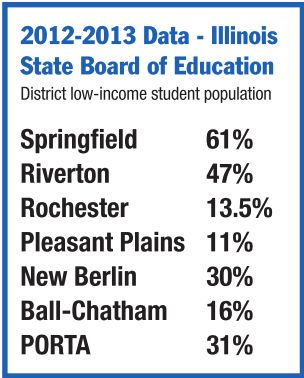

Manar

wants to make sure property-poor districts can afford to educate their

lowincome and special needs students. In addition to basing funding on a

district’s “ability to pay,” the proposed reform considers the number

of low-income students in the district. Low-income students are those

who are eligible to receive free or reduced-price school lunches.

The

proposed reform would also add extra weight to the funding formula for

other students with greater needs, such as advanced placement students,

alternative schools, gifted pupils, students with disabilities, and

Englishlanguage learners.

Ralph Martire, CTBA executive director, said Manar’s bill is one step toward improving the tax policy in Illinois.

“If

adequately funded, this bill would do a much better job of distributing

resources and it follows best practices. In those countries and/or

states that do a much better job of funding education, they

figure out what it takes to educate your typical kid, and then they say,

all right, not everybody is your typical kid, some have special needs,

some come from poverty, some are English-language learners. All of those

things cost more, to educate a kid with those backgrounds, than to

educate a kid who doesn’t,” Martire said. “This approach to education

factors in those characteristics that increase the cost of educating

children.”

The proposed reform also suggests adding extra weight to gifted students.

“For

the longest time we sort of ignored the fact that it’s more expensive

to provide an education to a really gifted kid than to a typical kid,”

Martire said. “This really changes that.”

Gaining support

While

Manar and the legislation’s cosponsors are working to gain support for

the proposed reform, many school superintendents are worried about

something more immediate. School leaders are simply hoping they don’t

receive any further cuts to their budgets this year.

Springfield

District 186 is facing a more than $4 million shortfall for the next

fiscal year beginning July 1. That’s if state funding is kept at the

same level as last year. While more equity-based funding would likely

help the district, which has about a 60 percent low-income student

population, right now its leaders worry about how much the district will

receive.

District 186

Interim Superintendent Robert Hill pointed out that if state education

funding levels are kept at the same rate, then changing the formula

would take away funds from some districts, though probably not

Springfield.

“When you

have the conversation that we’re having right now and you don’t put any

more money in, then it’s guaranteed, it’s a zero-sum game, there are

winners and there are losers,” he said.

Based on the legislation, Hill said, it looks like Springfield would be a winner.

Though

the debate seems to pit poor downstate schools against wealthier

suburban districts, Hill pointed out that there are some suburban

districts that are hurting just as much as downstate schools.

Thus,

the actual projections showing how districts would be financially

affected are what superintendents are waiting to see. Manar said the

Illinois State Board of Education is expected to release the

calculations in mid-May.

For

PORTA District 202 in Petersburg, the outcome of Senate Bill 16 isn’t

certain. Superintendent Matt Brue said that when he began as

superintendent 10 years ago, the district had about

18 percent low-income students, but now it’s close to more than 30

percent, due to a growing federal housing development.

The

district has higher property values than some nearby districts, but

it’s facing budget shortfalls because the district’s student population

has been declining.

In

addition to waiting on the bill’s numbers, Brue and his district are

waiting to see how much the state approves this year for education

spending. Over recent years, the district has had to cut back on its

spending. Instead of cutting staff to save money, Brue said, the

district has trimmed expenses by not filling positions when staff

members retire. As a result, Brue both serves as the district

superintendent and the cafeteria director. He said the district can’t

afford any deeper cuts in state spending.

In

order for Manar’s proposal to pass, Brue said, wealthier districts that

stand to lose general state aid may ask for “mandate relief.” The state

legislature passes laws, or mandates, every year that serve as

requirements for districts. For example, a bill pending in the Illinois

Senate would require schools to implement screening tests for children

entering kindergarten to look for signs of dyslexia. If a student shows

signs of dyslexia, the bill would require schools to offer a special

program. At PORTA, however, Brue said the district already has more than

30 specialized programs for children with reading disabilities that

ensure students are receiving the attention they need.

Both

Superintendent Hill of Springfield District 186 and Superintendent Brue

of PORTA said most leaders in Illinois would agree that school

districts do not need a long list of mandates in order to know what

students need.

“Parents have expectations,” Brue said.

“There’s

a reason we haven’t cut programs … I guarantee you that if school

districts have mandate relief, they’re not going to stop providing a

good education.”

Brue

said he thinks Manar’s plan is a good idea, and that most of the

property-wealthy districts would accept losing some of their general

state aid, especially if mandate relief is available.

Like school superintendents, legislators also are waiting to see the numbers behind school formula reform.

Convincing

the state’s leaders to agree on major policy changes is rarely a simple

task. Superintendent Hill said even 20 years ago, education funding

reform discussions were often based on something called “printout

politics.”

“They would

print out what the impact was going to be on every school district.

Every member of the General Assembly would get the printouts, look at

the schools that were in their legislative district … and it would

pretty much determine whether they would vote for or against it,” Hill

said.

Manar is hoping

that isn’t the case this time around. EFAC went through seven public

hearings and 45 hours of public testimony before releasing its findings

this year. Manar said all of that work wasn’t done for a “bickering

match.”

“Because if that was the case, I just wasted a lot of time and a lot of people’s time.”

A

number of groups have voiced their support for the bill, including

Advance Illinois, a group that works on education policy, the Chicago

Urban League, Ounce of Prevention Fund, a group that works with children

in poverty, the Illinois State Board of Education, the Illinois

Education Association, Stand for Children, Illinois Action for Children,

and the Illinois Business Roundtable. Additionally, former Gov. Jim

Edgar and Lt. Gov. Sheila Simon support the measure.

Yet

others have voiced concerns or opposition. In both the Senate Executive

committee and Senate Executive subcommittee, both of which approved the

bill, Republican members who were present either voted “nay” or

“present,” while all Democrat committee members voted in favor of the

bill.

Sen. Dale

Righter, R-Mattoon, voted against the legislation in committee. He said

the proposal will increase the funding system’s disparities and more

funds will go to Chicago public schools. A component of the bill is to

eliminate the Chicago Block Grant and filter funds for Chicago District

299 through the same formula as all other Illinois school districts.

Sen.

Righter also criticized the legislation as being drafted “in secret”

without discussion with EFAC’s Republican co-chair, Sen. Dave

Luechtefeld, R-Okawville.

Manar

said he had hoped politics would be kept out of the discussion. Manar

was displeased to hear that Sen. Righter had called in to a radio

station in Manar’s district and disparaged the bill.

“Actions like that, by Senator Righter, are the reason we haven’t been able to get this done in the state,” he said.

Manar’s

plan would phase in changes over four years. In the meantime, districts

are hoping to see no further cuts this upcoming school year. Over the

past two years, Illinois schools have been “prorated” at 89 percent,

meaning schools received 89 percent of the funds that the state says are

needed to provide the foundation level, or $6,119 per student.

Superintendent Hill said some leaders have heard an 83 percent proration

has been considered.

“It would be a doomsday scenario,” Hill said.

Contact Lauren P. Duncan at [email protected].