Prince of demagogues

Stephen A. Douglas and Illinois’ populist past

DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

The prospect is in store of two rabble-rousing populists trading insults for the next seven months. Each will try to tap the deep vein of grievance that runs through a middle class convinced that privileged interests (unions or the rich, it hardly matters) have robbed them blind. It’s all too depressing to look forward to, so I have been looking backward at some of the Illinois men who rose to power – or rather, who stooped to it – by cynically exploiting the popular prejudices of their day.

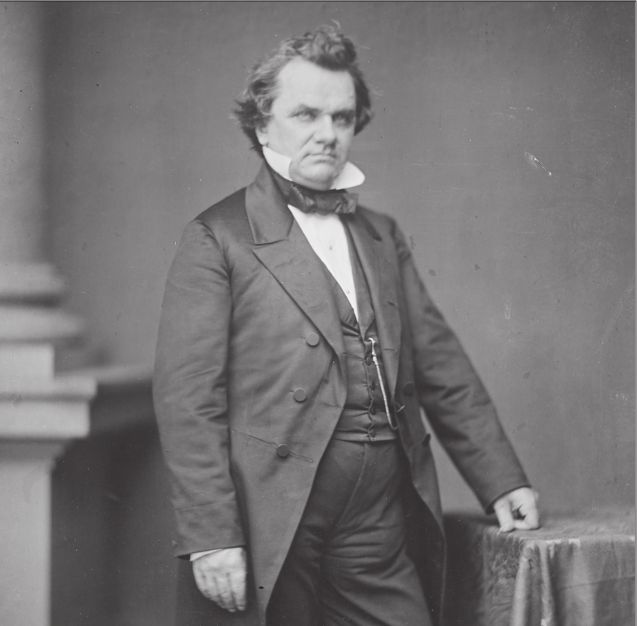

William Jennings Bryan, Salem-born and Jacksonville-educated, was one such mountebank. But Bryan merely wore a coat tailored to fit his predecessor of a previous generation, Stephen A. Douglas. The Little Giant was in fact a giant little man, meaning one whose energy and ambition enabled him to impose on large events the small spirit of our meanest citizens, specifically the Jacksonians who felt (and whose descendants still feel) disenfranchised by modernity.

Douglas’s memory has been ennobled by his long association with Lincoln, but he was anything but the Lincoln of the Democrats of their day. Judge David Davis of Bloomington once called him the prince of demagogues. Douglas was a walking, breathing attack ad. During his famous debates with Lincoln, he resorted to every low rhetorical trick to distort his opponents’ record and blacken Lincoln’s reputation. (Literally; he falsely accused Lincoln of wishing to mongrelize the white race.) Off the platform, he was a virulent white supremacist with a violent temper (he bit John Stuart’s thumb during an argument). As a lawyer he once stole a client’s money and spent it on a campaign, thus anticipating by more than a century our own disreputable system of campaign financing.

One historian exonerated Douglas of being aggressive, reckless, inconsistent and unscrupulous because, in the end, he remained steady in his love for the Union. This resort to patriotism as a defense for excess is always suspect, and more so in Douglas’s case. He has been praised for trying to chart a moderate course for the nation between abolitionists who wanted to destroy slavery even if it meant destroying the Union, and Southerners who wanted to save slavery even if it meant destroying the Union. The effort led one 1959 study of Douglas to describe him as “Defender

of the Union,” but we are entitled to ask whether a union that survives

only by countenancing slavery – Douglas’s union – is worth defending.

(We can also argue whether a union that survives only by military

conquest and repression – Lincoln’s union – is worth keeping.)

Douglas,

remember, helped start the slide to war in 1854, when he authored and

worked to pass the Kansas-Nebraska Act to advance the development of the

West, which set in motion the whole Indiankilling, territory-stealing,

farms-in-deserts madness of the age. He was an admirer of Andrew

Jackson, and like Jackson believed in Manifest Destiny. This, for those

who have forgotten, was the claim by Americans to a unique right to

behave in our continent as it now condemns Vladimir Putin for acting on

his. The land was ours (that is, white people’s) by right conferred by

God (that is, our God) so we could create a new heaven on earth. The

doctrine is odious and laughable in turn (in the end, we created

Scottsdale) but people still believe it. The difference today is that

Americans believe that our manifest destiny (which is somehow manifest

to no one else) applies not merely to the North American continent but

to the globe. Iraq was another Kansas.

Which

also triggered a civil war. To abet that expansion, he pandered to

Southern interests by agreeing to allow residents of new territories to

decide whether to admit slavery there. Southerners flooded into the

territory, and anti-slavery zealots rushed to oppose them, and blood

flowed.

“Let the

people decide” – as Bruce Rauner wishes to let them do about term limits

and as Pat Quinn hoped to do in 1994 – was high-sounding nonsense in

1854. Which people? (Neither slaves nor women got to decide whether and

where to extend slavery.) Granting people in the territories the right

to decide how to conduct their lives in their own local communities – in

effect, empowering exclusion and separatism – remains a seductive

doctrine to those who believe that the North American continent belongs

to the U.S., Indians and Mexican be damned, and that Americans don’t

need government as long as god-fearing white men have their guns. Those

Southern and Western states have been attempting to invoke their own

version of popular sovereignty when they assert a right to not enforce

federal laws on guns, immigration or health care. Were they to succeed,

they would realize that ideal republic envisioned by Old Hickory, and

nearly made real by the likes of Douglas.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].