What do the birds tell us?

Lessons from a 40-year study of the birds of Sangamon County

WILDLIFE | Jeanne Townsend Handy

Birds are at once well-known companions and elusive visitors. Many embark on enormous journeys, bringing with them the songs of spring and insights into the health of our surroundings. They belong to everyone and to no one, and it is no easy task knowing their numbers. What bird populations can be found in Sangamon County? What might they have to tell us?

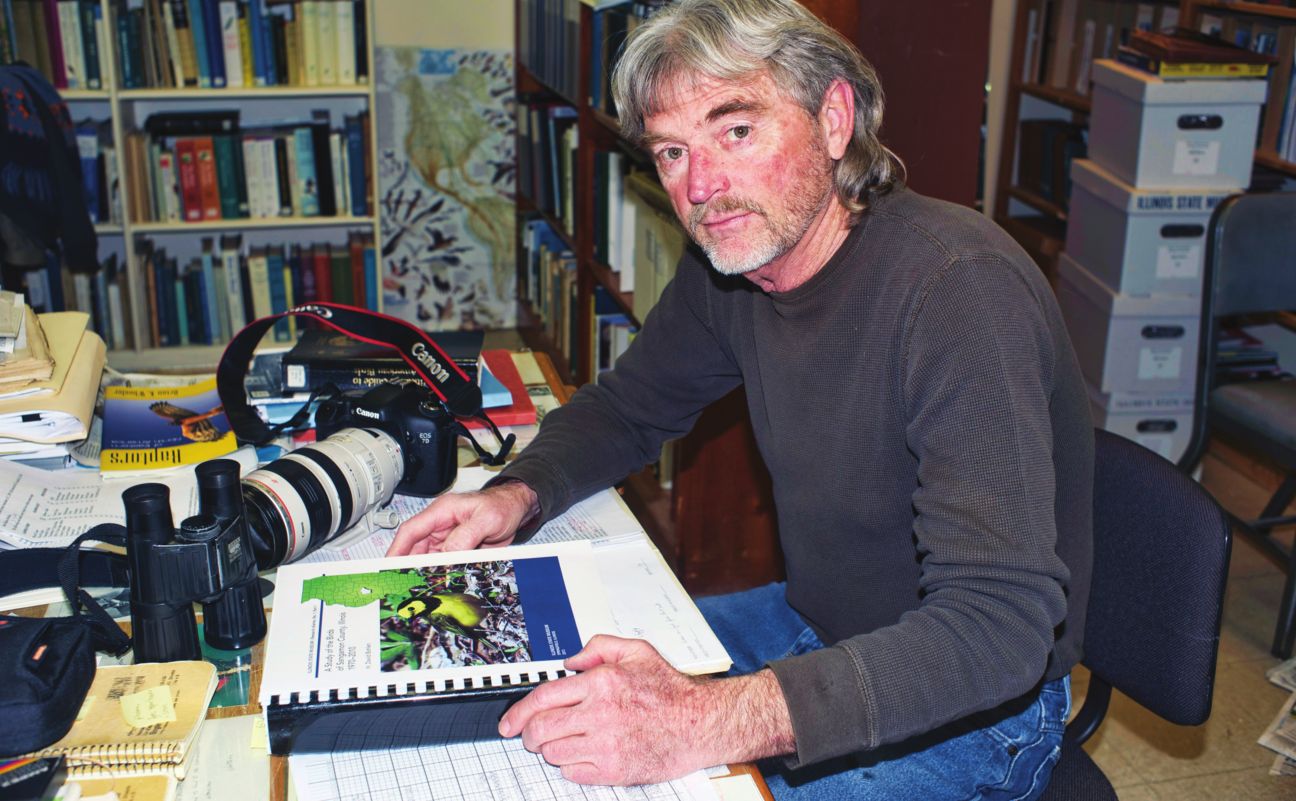

David Bohlen, assistant curator of zoology at the Illinois State Museum, has spent 40 years trying to answer these questions, as readily evidenced in the stacks of folders and files that have accumulated in his office over the course of his research. “I started out just wanting to write everything up, to have it all in one spot. And

then I started thinking how we don’t have much information on natural history in Sangamon County. This would at least be a chunk.” This “chunk” was released in January by the Illinois State Museum in a two-volume report called A Study of the Birds of Sangamon County, Illinois 1970–2010 and is the debut publication of its new Research eSeries.

For an average of more than 319 days a year for 40 years, Bohlen has visited numerous sites in Sangamon County, returning again and again to diverse habitats where he recorded 355 species, personally confirming each sighting. “I saw them or heard them or picked them up dead off the road. None were from lists from someone else,” he explains.

The resulting publication is not meant to be a bird identification guide. Bohlen’s goal has been to document the year-long residents, those that breed here and those that pass through Sangamon County as they follow migratory routes. Through the compilation of such data as arrival and departure dates, habitat changes, and singing dates, he has sought to discover trends and correlations, noting various species’ movements in tables and graphs. Volume 2 is filled with photographic documentation of the county’s birds as they go about their lives upon water, within trees and grasses, and in flight. While a few of the photographs are somewhat fuzzy representations of birds in action, most are

spectacular portraits of species that many of us have never encountered.

To care about the birds of Sangamon County, we must know them and their needs. By presenting studies of existing species and ongoing environmental processes, Bohlen provides research that will, tomorrow, become insight into our past. At the same time, it triggers thoughts of what the future may hold. This is no static story.

“During my study, a lot of things started changing,” he states, and the opening of Bohlen’s publication foreshadows his findings. In it he includes a dedication “to the native species of birds that have survived in Sangamon County.”

Building on a legacy

“[S]eek

another bird…and another…and still another. Soon there will grow an

acquaintancelist of birds which is one of the finest satisfactions of

this workaday world.” Virginia S. Eifert, Birds in Your Backyard, 1941

Bohlen states that very little was known about the birds of the county

prior to his study, but he notes that a list of 272 species did exist

dating from before 1970. The list was primarily compiled by Virginia

Eifert and Bill Robertson, and Eifert would go on to publish

introductions to many birds of Sangamon County and other parts of

Illinois in the Illinois State Museum publications, Invitation to Birds and Birds in Your Backyard.

Eifert

joined the staff of the Illinois State Museum in 1939, and she would

become a noted naturalist and author, producing 18 volumes of writing

and hundreds of articles on natural history subjects. Although Bohlen

notes that Eifert’s list of birds is somewhat anecdotal, through her

efforts we begin to understand the importance of documenting our

present-day species. Some of her descriptions now read like a

remembrance.

Of the Northern Bobwhite, Eifert writes:

“The

bobwhite fits into the Illinois scene… the running birds leap into the

air and glide on bowed wings into the grass; the bobwhite whistles, and

the countryside acquires new satisfaction.” How long has it been since

we have heard the “Bob-WHITE” call, familiar in childhood summers? And

what has become of the Loggerhead Shrike that Eifert refers to as a

common summer resident in central Illinois that “sings like a catbird or

a mockingbird, with innumerable mimickings, grace notes, and original

melodies rendered in a powerful tootling voice”?

With

Bohlen’s research, what may have been a vague and unsettling awareness

becomes confirmed fact. Northern Bobwhite numbers have dwindled in

Sangamon County, and the Loggerhead Shrike is one of the species of

which Bohlen writes, “It is greatly lamented that the following

interesting and unique species seemingly disappeared or were extirpated

as breeders as well as migrants.” Others included in this list of 15

species are the Upland Sandpiper, Whip-poor-will, Brown Creeper,

Bewick’s Wren, Cerulean Warbler, and the Western Meadowlark.

Bohlen

refers to his research as baseline data – a quiet, unobtrusive term for

a wakeup call. He notes that certainly things have changed since

Eifert’s time, but he adds that he did not have to look at the pre-1970s

information to recognize species disturbances. “During my study, a lot

of things started changing,” he states.

Sentinel species

“In nature nothing exists alone.” – Rachel Carson, Silent Spring, 1962.

Well

into the 20th century, miners brought canaries into coal mines as an

early-warning device since toxic gases would affect the birds first,

allowing time for escape. The notion of the “canary in a coal mine” has

become an enduring example of the advance notice of environmental

disruptions offered to us by other species.

Birds

are an especially important as a sentinel species – a species that

stands guard for the rest of us. Not only are they more susceptible to

potentially dangerous conditions, we are also more likely to take notice

of their losses. They have become for us symbols of freedom and peace

and can provoke powerful emotions, sparking action on their behalf –

perhaps before we may recognize a need to act for our own protection.

This

was the case when Rachel Carson published in 1962. The book opened with

“A Fable for Tomorrow” in which Carson described an imaginary spring

devoid of birds and their accompanying songs of the season. “No enemy

action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The

people had done it themselves,” she wrote. The book went on to present

scientific information about the threat to numerous species from the use

of DDT as a form of pest control. But it was the imagined spring

without birds that set off a public firestorm and helped prompt

President John F. Kennedy to take action. During an Aug. 29, 1962, press

conference, he confirmed that the

government was looking at the situation. “I think particularly, of

course, since Miss Carson’s book,” he stated. Eventually, the use of DDT

would be banned.

We

might know instinctively that threats to birds are likely to threaten

us as well. However, decisions must be based on data and not intuition.

Bohlen has discovered that 111 Sangamon County bird species are in

decline, and the table within the report titled “Species Status Change

in Sangamon County (1970- 2006)” offers associated findings as to why.

No marsh habit; urbanization; habitat loss.

These notations appear again and again.

Bohlen

asks us to consider that in 1830 there were 15 people per square mile

in Sangamon County. By 2008, the population per square mile had

increased to 222. In addition, 83 percent of unpopulated land was in

agriculture. “Every year there is less and less habitat for native

plants and animals in Sangamon County simply because there is less area

that has not been converted to human use,” he states.

But

beyond the aesthetic loss to human society, do lost habitat and lost

species really affect us? Can this be likened to a warning?

A report titled The State of the Birds, United States of America, 2009, which

was produced through a collaboration of numerous government agencies

and private organizations, uncannily mirrors Bohlen’s Sangamon County

findings. It, too, provides results from a 40-year study and reveals

“alarming declines for many of our most common and beloved birds.” The

report goes on to offer reasons why we should care, stating: “Birds are

bellwethers of our natural and cultural health as a nation – they are

indicators of the integrity of the environments that provide us with

clean air and water, fertile soils, abundant wildlife and the natural

resources on which our economic development depends.”

And

with Bohlen’s research we can no longer comfort ourselves with the idea

that the bird species we no longer see in our immediate area, within

our own backyards, are perhaps living comfortably somewhere – being taken care of by someone.

The

ban on DDT provides an example of the success that can follow increased

awareness and a willingness to act. Since DDT slowly accumulates in

each stage of the food chain, the pesticide nearly exterminated many of

our country’s birds of prey. Bohlen now lists 10 species that have

rebounded due to “DDT recovery” since the start of his study. These

include the Red-shouldered Hawk, the Great Blue Heron, the Snowy Egret,

and – the most heralded recovery of all – the Bald Eagle.

In

fact, 75 of the regularly occurring Sangamon County species increased

during Bohlen’s study, with some increases directly related to habitat

restoration. In addition, he documents other species that were rarely,

if ever, found in the county in the past. Others are migrating earlier.

But

even in the increasing numbers, in the seemingly good news, Bohlen has

sought correlations to the trends. Why are these changes taking place?

Phenology

“Their

northward fl ight keeps pace with unfolding bud and expanding leaf. The

sequences of nature, the timing of migration, are exact. Buds burst,

new leaves unfurl, larvae hatch, and warblers appear.” – Edwin Way Teale, North with the Spring, 1951

As defined in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, phenology is “a branch of

science dealing with the relations between climate and periodic

biological phenomena (as bird migration or plant flowering).” Bohlen

reports that 95 percent of the bird species in Sangamon County are

migratory, and he notes that some of the more profound changes he has seen are

related to the timing of migration. “I thought things were pretty

static, that this came at that date, and this is what happens. But no,

the whole picture changed,” he states.

Dr.

Eric Grimm, the Director of Sciences and the person at the forefront of

climate change research at the Illinois State Museum, claims that there

are two items of particular note in Bohlen’s research, and both of

these items refer to the value of data-supported knowledge. “It is no

longer just anecdotal about how things have changed, and [Bohlen] gives

the reasons why he thinks the changes have happened,” he states. “I

think the value of this, for climate change study in particular, is the

fact that it is baseline data for what we are seeing.”

In

addition to changes in migration, Bohlen has also documented a shift of

some species to the north, particularly the Blue Grosbeak and the

Black-necked Stilt. “I think there was one Blue Grosbeak recorded before

I started. Now they are fairly common in the summertime as a migrant,”

he says. He also witnessed an increase in many geese populations. “The

timing changed more than anything,” he adds.

So…birds

are coming earlier, and we are now more likely to see the extraordinary

Blue Grosbeak. Certainly this should be a bonus to central Illinois

bird lovers. But, as observed by the American naturalist and Pulitzer

Prize-winning writer Edwin Way Teale, the timing of migration is exact. The

larvae must hatch and the plants must pollinate before the migrants

arrive seeking these food sources. Disruption to a finely coordinated

strategy that has evolved over millennia can mean starvation.

In

addition, Grimm warns that shifts in species related to climate change

will not occur as we might imagine. “One of the things we know from our

studies of the past is that if big climate changes materialize as

projected, the shifts are not always as you would expect.” He states

that temperatures are getting warmer, despite the occasional plunges.

Trends in temperature can only be understood through documentation over

many years. And climate change, in fact, does not imply uniform warming.

Years of increased temperatures can cause a disruption in ocean

currents, which can, in turn, make temperate areas colder.

“You

might expect that southern species will just move north. Or, if it gets

colder, the northern species will just move south,” states Grimm. “But

that’s not what happens. They move all over the place. And, the

ecosystems that we have today will break up.”

To this Grimm adds the ongoing refrain.

“So again, having this baseline data is really important.”

The power of knowledge

“Who

is responsible for maintaining biodiversity? I would say the easy

answer is everyone…Why have an impoverished and uninteresting biota,

when we can have a diverse and fascinating one?” - H. David Bohlen Bohlen takes me into the bird specimen room adjacent to his office where drawers are filled with tiny

corpses and the shelves are lined with large, plastic-shrouded birds of

prey. Bohlen notes he has added several thousand Sangamon County

specimens to the collection since his arrival at the museum, although he

is quick to clarify that the large majority had been killed on the

roads or were causalities of transmission tower strikes.

I have to ask him – are there any Passenger Pigeons in the collection?

Bohlen

opens another drawer to reveal the few specimens held at the museum.

Here they are – the birds that are thought at one time to have been the

most numerous bird species on the planet. Population estimates from the

19th century range from 1 billion to close to 4 billion individuals, but

within only a few decades they became extinct, primarily from

unrestrained hunting and the clearing of forests. The last remaining

Passenger Pigeon died in captivity on Sept. 1, 1914. It is the ultimate

cautionary tale.

The

reminder of this great extinction is, in a way, the nudge needed to

realize that the publication of Bohlen’s study, despite its dire

implications, is good news for all of us. With knowledge comes awareness

and power. Future extinctions need not occur. We have the ability to

read the lyrical descriptions of Eifert and recall the recoveries

wrought, in part, by Rachel Carson’s publication of Silent Spring. And we can study the report of Bohlen that, through the launch of the Illinois State Museum’s Research eSeries, is free and accessible to all.

Bonnie

Styles, museum director, explains that the museum staff continues its

work in an ever-changing environment. Therefore this new format will

allow the museum to “easily update findings and present new versions as

new discoveries are made.” Even prior to publication, Bohlen added three

appendices to his report for data accumulated in the years 2010 through

2012. “I continue to monitor,” he states.

Bohlen’s report as well as The State of the Birds, United States of America, 2009 provide

recommendations for governments and citizens alike in the hope of

initiating actions that will reverse the current trends: protect

existing preserves and create new ones, create green space in urban

environments, landscape with native plants in backyards and parks, adopt

architecture and lighting systems that reduce collisions. We can all

play a role in supporting a diverse and fascinating world.

“Nature,

natural habitat, biodiversity, whatever one wishes to name it,” states

Bohlen “is one of those inalienable rights that everyone should be able

to enjoy.”

Jeanne Townsend Handy of Springfield writes about nature and the environment. Contact her at www.jthandy.com.