What to eat for a lucky New Year

FOOD | Julianne Glatz

“Ushers hurriedly passed tiny baskets of yellow grapes. A loud solemn gong began booming. Each head bent, gobbling their grapes. All around me I heard sputtering and choking. [Edmundo] was frantically consumed in the effort, swallowing even pits and stems. [He] turned to me, planting a damp kiss on both my cheeks.

‘Feliz año Nuevo, Aline – Happy New Year.’ Then he looked at my half-filled basket. ‘You didn’t finish your twelve grapes [before midnight.] That’s a bad omen for your 1944.’” –From The Spy Wore Red, by Aline, Countess of Romanones

Around the world, traditional foods are eaten on New Year’s Day to ensure 365 days of good luck. While they vary by region and culture, there are some striking – even surprising – commonalities.

Most auspicious foods for the New Year fall into six categories: grapes, greens, fish, pork, cakes and legumes. They are mostly considered lucky because of their shape, appearance, consistency, or even for some animals, their movements or habits.

The origin of Spain’s grape-gobbling custom, however, was wholly pragmatic. In 1909, grape growers in Spain’s Alicante region promoted the idea because of that year’s grape surplus. It quickly spread throughout Spain and Portugal and eventually to their colonies such as Venezuela, Cuba, Peru, Mexico and Ecuador. (Incidentally, the Countess Romanones’ memoir, above – and its sequel, The Spy Went Dancing – of her experiences as an American OSS spy in Spain during WWII and eventual marriage into one of Spain’s most aristocratic families, is a fantastic read, more like fiction that fact.)

I love greens such as spinach, collards, cabbage, kale and chard, though I’ve never associated them with money. But in places ranging from Denmark, Germany and the American South, cooked greens are said to resemble folded money - even sauerkraut! Supposedly the more of them in your stomach on New Year’s Day, the more cash will be in your wallet throughout the year.

One reason for eating pork on New Year’s Day is that pigs supposedly symbolize progress. More logical – at least to me – is that pork’s fat content – i.e. richness – is equated with wealth and prosperity. Regardless, eating pork on New Year’s Day is traditional in places around the globe.

In coastal regions, fish of varying sorts confer good luck at New Year’s. In Japan, specific fish are eaten for specific wishes: shrimp for long life, herring roe (eggs) for fertility, and dried sardines (formerly used to fertilize rice fields) for good harvests.

Cakes, most commonly round or ringshaped, can be found around the globe at New Year’s. In some places, a coin, whole nut, or other small object is hidden inside; the person whose piece contains the surprise is guaranteed extra-special good fortune for the coming year.

Perhaps the best known, most widespread lucky category of food that confers good luck for the New Year is legumes: beans, peas and lentils. Legumes have a

natural affinity with pork in all its forms: bacon, sausage, ham,

braised or roasted. Dishes combining the two, then, are especially

lucky, whether the Italian Cotechino sausage with lentils, Scandinavian

and German split pea soups with ham, New England baked beans with bacon

or salt pork, or the New Year’s Southern classic Hoppin’ John, made with

ham hocks and black-eyed peas. In Japan, sweet black beans are one of

the symbolic foods eaten during the first three days of the new year.

There

are also bad luck foods to avoid on New Year’s Day, such as lobster

(their backward movement means setbacks), or anything that flies (good

luck could fly away).

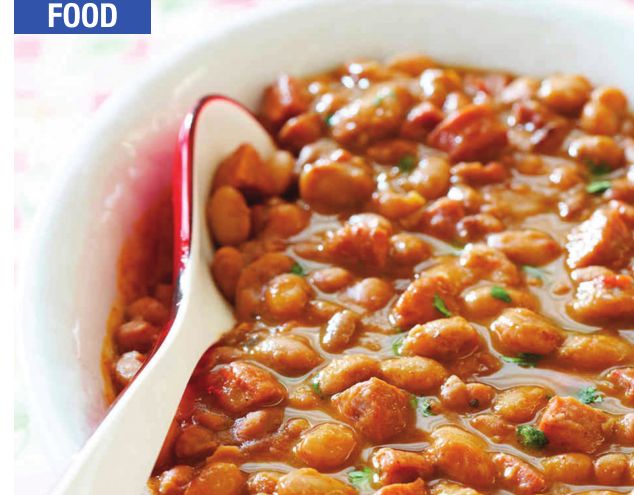

It’s

a funny name, especially if eaten after a night of imbibing. But the

“drunken” refers to a single bottle of beer, and the long cooking

eliminates virtually all its alcohol, making drunken beans appropriate

for even children.

Mexican drunken beans

• 2 c. dried pinto beans

• 8 oz. diced bacon, preferably slab

• 1 large white onion, diced

• 1 T. dried oregano, preferably Mexican

• 4 cloves garlic, chopped or sliced thinly

• 2 poblano chiles, seeded and chopped

• 12 oz. bottle of dark Mexican beer such as Negro Modelo

• 6 c. water

• Salt to taste Rinse the beans and pick over to remove any grit or

stones. Soak overnight in cold water at least 2 inches above the beans.

Alternatively, place beans in a large pot, add water to cover beans at

least 2 inches and bring to a boil over high heat. Boil for 1 minute,

then remove pot from the heat and let stand for 1 hour. Drain the beans

and reserve.

Put the

bacon in a large pot over moderately high heat and sauté just until the

bacon begins to render some fat. Add the onions, oregano, garlic and

poblano chiles and cook until the vegetables are softened and slightly

browned, 10-15 minutes. Add the beer and scrape up any of the browned

bits from the bottom of the pan.

Add

the beans and the water and bring to a boil. Reduce the heat to a bare

simmer, cover the pot, and cook until the beans are tender but not

mushy, about 1 1/2 to 2 hours. Add salt to taste. Allow to stand for

about 15 minutes, then check again for salt.

As

with many bean preparations, drunken beans are even better the next

day. If you are not planning to serve them the same day, rapidly chill

the beans to prevent spoilage. This is most easily done by placing the

beans in the container in which you plan to store them and then placing

the container in a large basin of ice water or very cold water. Gently

stirring the beans occasionally hastens the cooling process. Change the

water if necessary. When the beans have cooled to room temperature,

refrigerate immediately.

This

fantastic delicious, outrageously rich recipe is adapted from one that

appeared in the January 2008 edition of the now-defunct (and sorely

missed) Gourmet magazine. It comes from John T. Edge, founder of

the Southern Foodways Alliance and joyful advocate of American Southern

cooking and food traditions.

Creamed winter greens with brown butter

• 12 T. unsalted butter, divided

• 2 T. all-purpose flour

• 2 c. whole milk

• 2 T. minced shallot

• 1 bay leaf

• 6 black peppercorns

• 3 1/2 lb. mixed winter greens, such as collards, mustard greens and kale

• 6 oz. thick-sliced bacon, cut into 1/4-inch sticks (lardons)

• 1 c. finely chopped onion, not super-sweet

• 1/2 c. heavy cream

• 2 garlic cloves, minced

• 1 tsp. dried hot red-pepper flakes, or more to taste

• 1 T. cider vinegar, or to taste

Melt 4 tablespoons butter in a heavy medium saucepan over medium heat, then add flour and cook, stirring, 1 minute.

Add

milk in a stream, whisking, then add shallot, bay leaf and peppercorns

and bring to a boil, whisking. Simmer, whisking occasionally, 5 minutes.

Strain béchamel sauce through a fine-mesh sieve into a bowl, discarding

solids, and cover surface with parchment paper. Discard stems and

center ribs from greens, then coarsely chop leaves.

Cook

lardons in a wide 6- to 8-quart heavy pot over medium heat, stirring

occasionally, until golden-brown but not crisp, about 8 minutes.

Transfer lardons to paper towels to drain, then pour off fat from pot,

reserving for another use.

Heat

remaining 1/2 stick butter in pot over medium-low heat until browned

and fragrant, about 2 minutes, then add the onion, and cook, stirring,

until softened, about 3 minutes.

Increase

heat to medium-high, then stir in greens, 1 handful at a time, letting

each handful wilt before adding next. Add béchamel, cream, garlic,

red-pepper flakes, 3/4 teaspoon salt, and 1/2 teaspoon pepper and boil,

uncovered, stirring, until sauce coats greens and greens are tender,

about 10 minutes. Stir in lardons, vinegar, and salt and pepper to

taste.

Contact Julianne Glatz at [email protected].