FOOD | Julianne Glatz

Cookies and Christmas. Is there any more universally traditional food of the holiday season? Sure, there’s fruitcake, though many people regard it as something best avoided rather than embraced – but everybody loves cookies. Even folks like my dentist husband, Peter, who doesn’t care for sweets, eats cookies during the holidays.

For years, one of the most anticipated events of the season at his office was the arrival of Velma Mayes’ Christmas cookies. Mayes, a legendary Italian-American cook from Springfield’s north side, would fill a huge box with her traditional specialty: crisp wafer-thin pizzelles, fried cookies such as cenci alla fiorentina and rosettes and more. Her husband, Wayne, delivered them. When I’d hear that Velma’s cookies arrived, I’d stop by the office to snag some before they disappeared.

The antecedents of cookies appeared as long as 10,000 years ago. Archeologists discovered that Neolithic farmers baked a mixture of grain, water and “paste” on hot stones. Though we would undoubtedly find the resultant product unappetizing, it provided sustenance and was the ancestor of the cookies and crackers we eat today.

Sweetened cakes and cookies became a part of festivals and holidays long before the advent of Christianity, especially pagan winter-solstice festivals. It’s believed that part of the reason Pope Julius I made Dec. 25 the official date for celebrating Christmas was to incorporate some of those pagan traditions, such as cookies and bringing evergreen trees and boughs into homes. The reasoning was that by doing so, Christian Christmas would seem a natural extension of familiar rituals and thus encourage converts.

Those early cookies were sweetened with honey. Middle Eastern bakers discovered that eggs and butter lightened their texture, and in the seventh century in Persia (modern-day Iran), sugar came to be used in cookie and cake making. Middle Eastern cookie recipes and techniques spread into Europe as a result of the Muslim invasion of Spain, the Crusades, and the spice trade. By the 1500s, Christmas cookies were the rage all over Europe. In Germany there were Lebkuchen (gingerbread cookies) and Springerle (stamped cookies flavored with aniseed). Swedish pepparkakor had not only ginger but also black pepper. In Norway, krumkake were flavored with lemon and cardamom.

Our word “cookie” comes from the Dutch word koeptji or koekje (“small cake”), brought to America in the 1600s by the earliest Dutch settlers. A recipe for “Christmas Cookey” appears in a book considered by most food historians to be the first American cookbook, American Cookery by Amelia Simmons, published in 1796: “To three pound flour, sprinkle a tea cup of fine powdered coriander seed, rub in one pound butter, and one and half pound sugar, dissolve three tea spoonfuls of pearl ash [a rising agent, predecessor to baking soda and powder] in a tea cup of milk, kneed all together well, roll three quarters of an inch thick, and cut or stamp into shape and size you please, bake slowly fifteen or twenty minutes; tho’ hard and dry at first, if put into an earthern pot, and dry cellar, or damp room, they will be finer, softer and better when six months old.”

I just hope they weren’t moldy. Spices such as the coriander in that 1796 recipe and caraway seeds (which appear in a somewhat similar recipe from 1845), have largely disappeared from American Christmas cakes and cookies, but others, including ginger, cinnamon and cloves, remain popular. Those early rolled or stamped cookies were usually cut or molded into

simple shapes: circles, squares, diamonds or hearts. Beginning in 1871,

however, a flood of cheap imported cooking utensils from Germany

included the first elaborate cookie cutters. Suddenly cookies in shapes

such as Santas, Christmas trees, angels, stars, bells and even camels

were possible. Sometimes flavor and texture suffered in the pursuit of a

firm dough that could be cut into such complex shapes; unfortunately,

the same holds true today.

These

days there’s an even more extensive and incredible variety of Christmas

cookies. It would be interesting – though probably impossible – to find

out exactly just how many different kinds of Christmas cookies, new and

old, are being made this year.

The macadamias in this recipe make it an especially luxurious holiday treat.

Salted macadamia white chocolate bars

For the bottom layer:

• 1/2 c. unsalted butter, at room temperature

• 1/2 c. light brown sugar

• 1 c. unbleached all-purpose flour

• 1/2 tsp. salt

For the top layer:

• 2 large eggs

• 1 c. light brown sugar

• 1 tsp. vanilla

• 1 tsp. baking powder

• 1/4 unbleached all-purpose flour

• 1/2 tsp. salt only if nuts are unsalted

• 1 c. best quality white chocolate chips, such as Ghiradelli

• 1 c. macadamia nuts

• 2 tsp. to 1 T. coarse sea salt

Preheat

the oven to 375 F. In a mixer, food processor or large bowl, mix

together the ingredients for the bottom layer until thoroughly combined.

Press into an even layer on the bottom of a 9-inch by 13-inch pan. Bake

for 10 minutes, then cool to room temperature.

In

a mixer, food processor or by hand, whisk the eggs and brown sugar

together until thick and smooth and then stir in the vanilla. Combine

the baking powder and flour (and the salt, if using) and stir into the

egg/sugar mixture. Stir in the nuts and white chocolate chips. If you

are using a food processor, do this by hand so the nuts and chips don’t

get chopped up. Spray the sides of the pan with cooking spray and then

pour the top layer evenly over the bottom crust. Bake for 20-25 minutes

or until just set. Immediately sprinkle with the coarse salt. Cool and

then cut into squares or triangles. Yield will depend on cookie size.

Variations: use

other nuts, such as pecans, walnuts or hazelnuts and/or milk, semisweet

or bittersweet chocolate chips. The cookies can also be made with just

nuts or just chocolate chips (if using just chips or nuts, increase the

amount to 2 cups.) The bars can also be made without the sprinkling of

coarse salt.

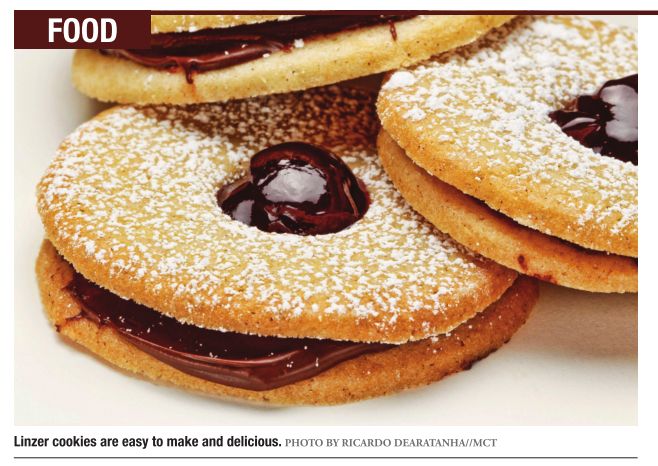

Linzer

tortes are one of Austria’s most famous pastries – more pie than cake: a

ground-nut (usually hazelnuts or almonds) dough scented with lemon peel

and cinnamon, filled with raspberry jam and topped with a latticework

of the same dough. Linzer cookies are just a delicious as that old-world

specialty and far easier to make.

Linzer cookies

• 1 1/2 c. butter

• 1 c. sugar

• 2 eggs

• 1 T. lemon rind, not packed

• 1 tsp. vanilla

• 3 c. lightly toasted, then finely ground hazelnuts or almonds

• 4 1/2 c. cake flour

• 1 tsp. baking powder

• 1 tsp. cinnamon

• 12 oz. seedless red raspberry jam

• Powdered sugar, optional

Cream

butter with paddle attachment. Add sugar and continue creaming. Add the

egg, lemon and vanilla and mix. Blend in the ground nuts.

Stir

together dry ingredients, add to mixer, and blend thoroughly. Form into

disks, wrap and chill until firm. On a floured surface, roll out dough

with floured rolling pin to approximately 1/8-inch thickness on a

floured surface.

Cut

out disks or other shapes approximately 2 inches in diameter. Cut out

the centers of half the disks with a cutter in the shape of your choice.

Reroll scraps and repeat.

Chill the cut-outs thoroughly.

Preheat the oven to 350 F. Bake for about 12 minutes or until edges turn golden. Cool on a wire rack.

Warm

the jam just until it is fluid. Spread the solid disks with a layer of

the jam. At this point, you can place the lids on the top if not using

the powdered sugar. Press down lightly on the lids.

If

using the powdered sugar, put the powdered sugar in a sieve and

sprinkle the tops lightly. Press on the bottom halves as above, holding

only by the edges.

Alternatively,

place the tops on the jamspread bottoms, sprinkle with the powdered

sugar, and then fill the holes with more jam. Let set slightly before

serving.

Contact Julianne Glatz at [email protected].