FILM | Chuck Koplinski

Grand performances move Hustle

Deception, denial and blind ambition are at the core of David O. Russell’s American Hustle, a wildly ambitious, relentlessly engaging and darkly humorous tale that features not only some of the best film acting of the year but also one of the sharpest scripts in recent memory. To say that the filmmaker has Hollywood’s hottest hand right now is an understatement as he resurrected his career in 2010 with The Fighter, followed that up with last year’s Silver Linings Playbook and continues to impress with this partly fact, partly fiction, tale of the FBI’s Abscam Operation from the late 1970s and early 1980s.

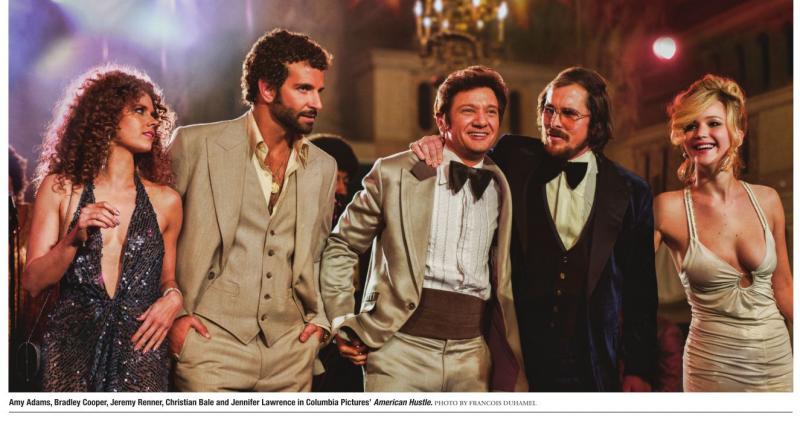

The film begins, not by telling us that what we are about to see is a true story, but that “Some of this stuff actually happened.” Immediately, Russell lets us know that discerning what’s true or false isn’t important – the fact that honest human behavior is on display is. The tainted conscience at the core is Irving Rosenfeld, a small-time hustler with dreams of grandeur, which grow even larger once he falls for Sydney Prosser (Amy Adams), a one-time stripper with razor-sharp survival instincts. They set up a successful scam where they promise desperate people to look into bogus loans for a $5,000 fee. This gets the interest of Richie DiMaso (Bradley Cooper), an FBI agent whose ambition far outweighs his intelligence. He busts the duo but cuts them a deal – help him entrap some high rollers and after four arrests they can walk. Prosser urges Rosenfeld to leave the country with her but he refuses to leave his adopted son and psychotic wife Rosalyn (Jennifer Lawrence).

Allegiances are tested, promises are broken and paranoia sets in as no one knows who’s scamming whom. Where survival among cutthroats is concerned, both trust and innocent people end up being collateral damage. Tangled in this is Mayor Carmine Polito (Jeremy Renner), a man of the people who unwittingly becomes involved with this sting operation, desperately seeking funds to rebuild Atlantic City and jumpstart the economy.

What’s surprising is that the moral center of the film is Rosenfeld. Bale gives us a perfect performance, vacillating between rage, desperation, guilt and greed. Cooper matches him as DiMaso slowly coming unglued, going from sly to manic in a heartbeat while Adams gives us a little girl lost who has no problem using sex as a weapon. But if there’s a scene-stealer in the film, it’s Lawrence. She provides a sly comic creation, a woman who justifies her insane actions with a kind of circuitous logic that defies all reason and proves hilarious.

Russell isn’t telling us anything new – that the American Dream is only attainable by hook or by crook – but rarely has such an indictment been as lacerating, insightful and witty. American Hustle is not just a movie for our times but for all times. It mercilessly reminds us that survival at any cost is the name of the game. The arena may have changed over time, but the players – the crooked, the desperate and the innocent – remain the same.

Human element and dazzling visuals save Smaug

It was once said of director Oliver Stone that he was much like Lennie from Of Mice and Men: he could take any good idea and smother it to death just as Steinbeck’s tragic figure does to mice and lonely women. I’d put director Peter Jackson in the same category. There’s no denying he’s a very talented man and a gifted filmmaker, but he’s not one to heed the advice that there can be too much of a good thing.

Take as proof his latest, The Desolation of Smaug, the middle segment of his three-part adaptation of J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit. Without question, it’s a visual knockout. Jackson and his army of computer artists have fashioned the most lush, gorgeous and horrifying world that pixels can create. The director’s meticulous (obsessive) nature is also on display as every single narrative event from Tolkien’s novel and some borrowed from others are included here, much to the delight of the book’s aficionados and the discomfort of the rest of us.

The

film picks up with Tolkien’s band of heroes – the wizard Gandalf the

Grey (Ian McKellen), the hobbit Bilbo Baggins (Martin Freeman) and 12

dwarves led by Thorin (Richard Armitage) – in dire straits. They’ve set

out to reclaim the mountain kingdom of Erebor from the malevolent dragon

Smaug (voice by Benedict Cumberbatch) but are being pursued by the

ever-ugly Orcs who wish to kill them. Before reaching their destination,

they must also travel through an evil forest, battle a nest of giant

spiders (arachnophobes, abandon the notion of facing your fears and go

get popcorn during this sequence – it is incredibly frightening), and

end up being captured by elves.

The

movie is a visual wonder and in order to fully appreciate Jackson’s

vision, seeing it in 3-D is a must. To be fair, the story moves along at

an acceptable pace until the third act, when Bilbo finally reaches

Erebor to confront Smaug. What begins as a tense encounter ultimately

becomes tedious. Our hero and eventually Thorin and a couple of his

vertically challenged friends traipse around the enclave on mountains of

gold with the scaly serpent in hot pursuit. Jackson is obviously quite

taken with his creation, giving the character far too much screen time.

His decision to end this segment where he does, while an effective

cliffhanger, is almost cruel in the way it treats its audience.

Still,

there’s enough of a human element at play to keep the film grounded.

McKellen continues to be the franchise’s best friend, bringing a gravity

to the proceedings that would devolve into silliness without him.

Freeman is very good as well, doing a wonderful job portraying Bilbo’s

slow descent into madness as he lets the magical ring he covets corrupt

him. For me, this is the crux of the epic. Thankfully Jackson tears

himself away from his computer-generated creations to devote enough time

to this theme.

Davis a tribute to art for art’s sake

When

you look at the modern state of American cinema, it’s something of a

small miracle that the Coen Brothers are able to make films in today’s

marketplace, let alone build the body of work that they have. They’re

two of the lucky ones, having found success while staying true to their

aesthetic. Big box office has never been the driving force behind their

work; they’ve always adhered to their own personal vision, eschewing the

notion that profit should be put before their art.

One sees that belief at play in their latest film Inside Llewyn Davis, a

love letter to the folk music movement of the 1960s. It concerns one

talented artist whose tenacity is tested by forces that have seemingly

conspired to thwart him. Oscar Isaac takes on the title role and it’s a

difficult one to realize, as Davis is hardly a likable character. He

isn’t short on talent, as evidenced in the very first scene, in which he

performs a heartbreaking rendition of the folk classic “Hang Me, Oh

Hang Me.” However, he has a way of rubbing people the wrong way, putting

forth an air of superiority as

he nobly travels the struggling artist’s trail. He pays no mind to the

practicalities of life, sleeping on the couches of one acquaintance

after another, bumming money from whomever he can. He has no problem

having casual sex with women, among them his friend Jim’s (Justin

Timberlake) wife Jean (Carey Mulligan), who may be pregnant.

Yep,

he’s a lout, but he stays true to his music and his talent, which he

puts on the line when he takes a road trip to Chicago in hope of getting

the attention of agent Bud Grossman (F. Murray Abraham) who has the

power to save his career. It’s during this trip that we see Davis put to

the test, having to endure the companionship of two boorish car mates –

Roland Turner (John Goodman) and Johnny Five (Garrett Hedlund) – and

caring for a cat that fate has put into his care. His true colors emerge

as his capacity for empathy and his devotion to his art are put to the

test.

In

the way Davis is portrayed, one gets the impression that the Coens have

gone down this road themselves. Balancing one’s passion with financial,

moral and societal responsibilities is not everyone’s forte. That we

ultimately sympathize with Davis is a credit to Isaac’s ability to flesh

out the grey areas of this complicated man. In the end, the film is a

tribute to all artists who persevere in the face of crushing adversity,

those who hold tight to their passion despite a chorus of naysayers.

Though these people may be flawed, the Coens have succeeded in showing

us that nobility can be found in what others may see as a fool’s quest.

Mr. Banks is short on key details

This behind-the-scenes story about the making of the big-screen version of Mary Poppins is

an intriguing one. Film impresario Walt Disney ran into a great deal of

resistance from the author of the movie’s source material, P.L.

Travers, a set of circumstances that was unusual for the creator of the

“Happiest Place on Earth,” who was used to having each of his wishes

carried out. What resulted was a battle of the wills between two artists

with distinctly different visions of how to present a beloved

character. The battle would tax the patience of each of them.

When we first meet Travers (Emma Thompson) she’s in dire financial straits. Sales of her novel, Mary Poppins, have

dried up and, though the wolf might not be at the door, her security is

threatened. Disney (Tom Hanks) has been pursuing the rights to her

novel for years and only out of necessity does she agree to go to

Hollywood to meet with the potential makers of the film adaptation to

hear their ideas. This gets off to a disastrous start as she resists the

notion that the movie be a musical and she forbids the use of animation

to be any part of the production. Things go from bad to worse as she

ultimately abandons the idea of turning her beloved novel into a movie,

maintaining the integrity of her creation.

When we first meet Travers (Emma Thompson) she’s in dire financial straits. Sales of her novel, Mary Poppins, have

dried up and, though the wolf might not be at the door, her security is

threatened. Disney (Tom Hanks) has been pursuing the rights to her

novel for years and only out of necessity does she agree to go to

Hollywood to meet with the potential makers of the film adaptation to

hear their ideas. This gets off to a disastrous start as she resists the

notion that the movie be a musical and she forbids the use of animation

to be any part of the production. Things go from bad to worse as she

ultimately abandons the idea of turning her beloved novel into a movie,

maintaining the integrity of her creation.

As

directed by John Lee Hancock, the film does a fine job of segueing

between the production woes and flashbacks Travers has in which we see

glimpses of her childhood, key incidents that are supposed to show us

how the Poppins character came to be. However, the major fault of

the movie is that we find out very little about her Aunt Ellie (Rachel

Griffiths), who was the inspiration for the magical nanny. She appears

midway through the film, has perhaps three scenes and, though she does

save Travers and her family after a fashion, the movie does not provide

any insight as to what this person did to make such an impression on the

author.

The film’s saving grace is its solid cast.

It

comes as no surprise that Hanks and Thompson deliver solid turns, with

the former avoiding the trap of providing an imitation of Disney and

rather offering up his own interpretation. Thompson succeeds with the

more difficult task – making her thorny character understandable and

sympathetic. B.J. Novak and Jason Schwartzman as the songwriting duo

Robert and Richard Sherman have some fine moments as the frustrated

music makers, while Paul Giamatti as Travers’ chauffeur delivers some

unexpectedly poignant moments, as he’s the only person who manages to

bond with the troubled author. If anyone is getting short shrift it’s

Colin Farrell as Travers’ father, a troubled man unable to control his

own demons. It’s a sympathetic and mannered portrayal that provides the

emotional underpinning of the film, something that’s lacking during

other key moments.

Contact Chuck Koplinski at [email protected].