Springfield man alleges racial profiling by city police

LAW | Patrick Yeagle

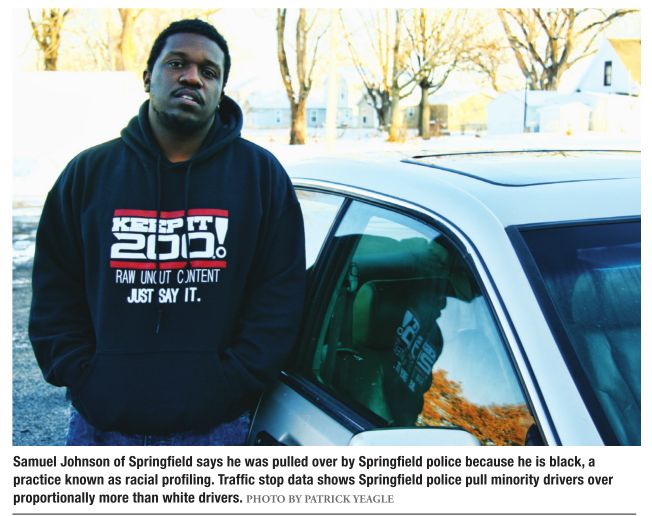

Samuel Johnson knew something was up before he even left the highway.

Just before midnight on Nov. 4, Johnson was returning from Bloomington in his Mitsubishi Diamante when he spotted a Springfield police vehicle parked at a U-turn on I-55. He noticed that the police pulled out behind him and followed from a distance as he signaled his exit onto Clear Lake Avenue. He also noticed a second police vehicle parked at the BP-Circle K gas station just off the interstate.

Johnson used his turn signal to change from the right lane of Clear Lake Avenue to the left lane. Shortly after crossing Dirksen Parkway, Johnson saw the dreaded blue and red lights in his rearview mirror. He pulled into the parking lot of Casey’s General Store, 3001 E. Clear Lake Ave. Two Springfield police officers approached the car, one on either side. Although Johnson did signal his lane change, he was being pulled over for not signaling for the full 100 feet required by state law.

To Johnson, who is black, it was just the first sign he was being racially profiled. Acting Springfield Police Chief Kenny Winslow said he couldn’t discuss the stop because of the pending court cases.

“I don’t think it has anything to do with racial profiling,” Winslow said, declining to discuss specifics of the case.

Still, traffic stop data collected by the state shows Springfield police stop and search minority drivers far more often than white drivers.

The official police report in Samuel Johnson’s traffic stop says the police looked Johnson up in a criminal background database and found five previous arrests for dangerous drugs. When the officer returned to give Johnson a citation for improper turn signal usage, he asked Johnson to step out of the car and sign the citation.

Johnson denies he has been arrested five times for dangerous drugs, though he admits he was arrested once in 2001 for possession of cocaine while he was in college. The charges in that case were dropped.

Believing himself innocent of any wrongdoing, Johnson refused to step out of his vehicle and was arrested for resisting a police officer. Johnson believes the whole stop was a pretext to search his vehicle for weapons and drugs because of his skin color. A police drug dog sniffed the car and found nothing, and officers who searched the car after Johnson’s arrest also found nothing. Johnson is currently fighting his ticket for failure to signal a lane change and his misdemeanor charge of resisting an officer.

Johnson’s stop isn’t an isolated incident.

Annual traffic stop data from the Illinois Department of Transportation shows that minority drivers are estimated to make up 20.56 percent of the city’s population, but they account for 38.62 percent of all traffic stops by city police in 2012.

The disparity in traffic stops was less pronounced in 2012 than in the previous four years. For comparison, IDOT divides the percentage of minority traffic stops by the percentage of minority driving population to obtain a ratio. A ratio of 1.0 would mean minority drivers are pulled over in proportion to their share of the population. In 2008, that number was 2.47, but it improved to 1.88 in 2012.

Additionally, black drivers in Springfield are more likely to be asked to consent to a search of their vehicle, although white drivers are more likely to actually have contraband in their vehicles. Of the 665 consent searches performed by Springfield police, 386 were on minority-driven vehicles, while 260 were on vehicles driven by whites. The consent searches found contraband in 32 cases, or 8 percent, for minority drivers. Consent searches of cars driven by whites found contraband in 30 cases, or 12 percent.

Springfield police used drug dogs on 61 cars driven by minorities in 2012, compared with only 30 for white drivers. Despite using drug dogs on minority cars more than twice as often, the dogs found contraband in only six cars driven by minorities, but they found contraband in seven cars driven by white drivers.

The data show the dogs gave false positives most of the time. While the dogs alerted their handlers 50 times in 2012, contraband was only found 13 times as a result of an alert, meaning the dogs had a successful find rate of only 26 percent.

Samuel Johnson’s experience has had at least one positive outcome. During the stop, Johnson told the officer that he was recording the stop on his camera phone. The officer ordered Johnson to stop, saying state law forbade Johnson from recording police on duty. That state law was found unconstitutional by a U.S. Court of Appeals in May 2012, essentially making it legal to record audio of police who are on duty and in public. Winslow sent out a department-wide memo last week telling his officers about the decision.

Johnson says as a black driver, he has to be aware of his skin color every time he gets behind the wheel.

“It’s unfair that every time the police come around, you have to feel unsafe,” he said. “When you see them, you feel uncomfortable. You know there’s a possibility that you’ll get pulled over for no reason and have to go through the protocols just because you’re black.”

Despite his experience, he says he harbors no hate toward the Springfield Police Department or the individual officers involved in his stop.

“We need to start to rebuild a relationship between citizens in certain communities and the Springfield Police Department,” he said. “We have to have some kind of relationship, because at the end of the day, the police have to protect the community, and the community has to feel safe. We have to have a better relationship. My first objective is unity. Once we get a little closer to that, I think a lot of problems can get solved.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].