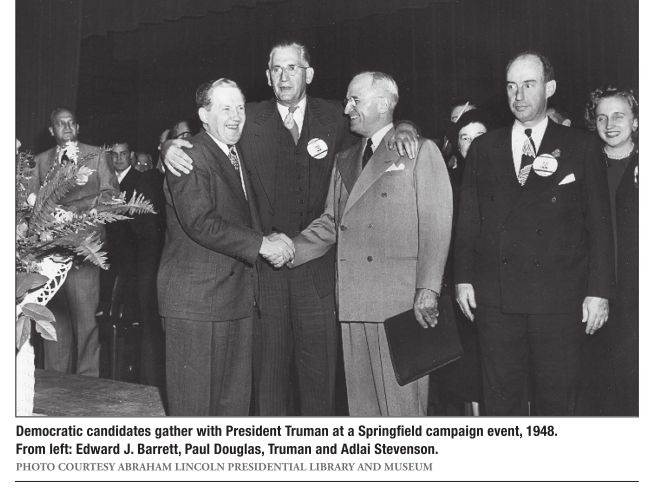

The surprising election that gave us Stevenson, Douglas, Truman and plenty of intrigue

BOOK REVIEW | Robert D. Sampson

Battleground 1948: Truman, Stevenson, Douglas, and the Most Surprising Election in Illinois History, Robert E. Hartley, Southern Illinois University Press, 206 pp., illus., notes, bibliography and index.

Given our state’s convoluted, complex, and at times outright Byzantine political history, tagging any election as the “most surprising” sets up great expectations in a reader’s mind. Robert E. Hartley, the former editor of the late, lamented Lindsay-Schaub Newspapers, Inc., which operated dailies in Decatur, Carbondale, Urbana and East St. Louis, more than fulfills that standard.

A smooth writer who melds significant facts into flowing prose, Hartley examines a significant election for the nation – and the state. Those recalling the 1948 contest likely associate it more with President Harry Truman’s upset victory over the complacent favorite, New York Gov. Thomas Dewey, perhaps noting as a side effect the victories of Adlai E. Stevenson II for governor and Paul Douglas for U.S. senator. This book, however, will put the horses – Stevenson and Douglas – in their proper place, ahead of and pulling Truman in the cart.

Behind the victories of the whistlestop campaign Truman and the good government (“goo-goos,” as the old Daley Machine might say) Stevenson and Douglas, was an almost unbelievable series of scandals, political miscalculations and resulting newspaper outrage that buried the powerful incumbent governor, Dwight Green, and the Chicago Tribune-controlled U.S. senator, Curly Brooks, beneath a mountain of voter outrage.

The roots of the electoral landslide can be found, as Hartley convincingly demonstrates, in a series of events beginning with the 1947 Centralia Mine Disaster (the topic of another Hartley book) that tragically revealed the blatant politicization and unconcern with safety in the state’s Department of Mines and Minerals. Green, a popular two-term incumbent who hungered for the vice-presidential nomination, issued the appropriate platitudes and avoided any serious action to address those problems, yet still seemed a likely victor over Stevenson.

Hartley, using the papers and memoirs of Illinois political leaders of the time, retells the familiar story of the state Democratic Party’s unlikely selection of Stevenson and Douglas as its standard bearers. Stevenson, distant and distracted at times, seemed little competition for the experienced Green. Douglas, an energetic and effective campaigner but underfunded, appeared to pose little threat to the bombastic Brooks who had already won two elections for his seat and counted on the undying support of Colonel Robert McCormick’s isolationist, New Deal-hating Tribune that reached into nearly every crossroads and corner of the state.

And then a gunshot changed it all.

And then a gunshot changed it all.

There

is not enough room here to describe fully the chain of events cascading

from the assassination in Peoria of Bernie Shelton, the notorious head

of a Downstate gambling and prostitution empire. Plus, Hartley’s

exploration of that process is worth more than the price of the book. It

is a pleasure best left for a reader to enjoy.

Suffice

it to say that Shelton’s death revealed a shocking pattern of payoffs

and shakedowns orchestrated by Green’s administration and local and

county officials to protect illegal activities in return for large cash

contributions. Leading the charge in exposing this network, which almost

makes today’s “pay-to-play” climate look benign in comparison, was the St. Louis Post-Dispatch newspaper and its ace crime reporter, Theodore C. Link.

Nearly every day from August to November, the Post-Dispatch hammered

Green and his administration, labeled the “Green Machine,” with exposé

after exposé. Desperate to stem the barrage by discrediting the source,

Green and his attorney general engineered the indictment of reporter

Link by a Peoria grand jury. For Illinois voters that was, as they say,

the last straw.

Hartley’s

book provides all sorts of treats and insights in telling this story.

They range from the role of newspapers in what would be their last

hurrah of political effectiveness, to the peculiar nature of Adlai

Stevenson as a candidate, to the inanities of Brooks who surely will

continue to rank among the most embarrassing and least effective men and

women to represent Illinois in Washington, to the rise of Paul Powell

and his origins in a southern Illinois gang of freebooters and spoilsmen

who played an important and decisive role in the 1948 campaign.

Retired

from public relations, a field he entered after leaving the newspaper

business, Hartley has profitably devoted the past two decades to

producing one significant book after another on Illinois history. His

biographies of Powell and Paul Simon are must-reads for anyone seeking

to understand the bad and the good of 20 th century political life in

our state. His latest book adds to an already distinguished body of

work.

Robert

D. Sampson is an instructor of history at Millikin University, a former

reporter and local elected offi cial in Macon County.