Why do so many cities with history not have a history?

DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

Most towns of any size have history that is worth reading about, but surprisingly few have a good history in which they might read it. By “a good history” I mean a single-volume history for the intelligent and curious reader that is comprehensive and up to date. Springfield and Sangamon County has had fine books written about it, but its only general history (Helen Van Cleave Blankmeyer’s The Sangamon Country) was written for eighth-graders in the 1930s; I mean no insult to the eighth-graders of the 1930s when I say that this will not do.

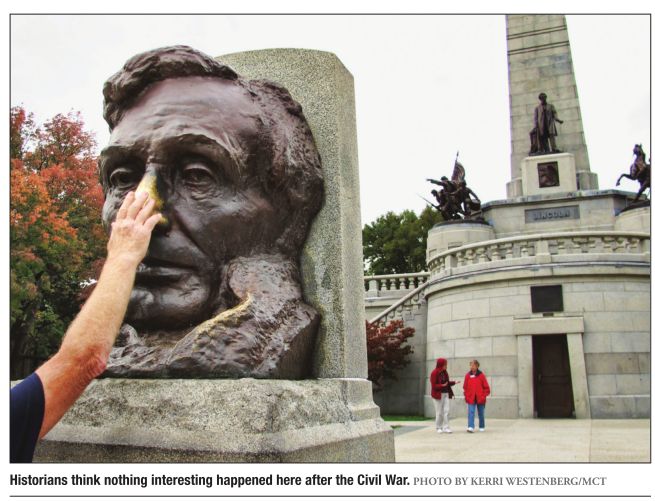

Historians are drawn to the frontier era like sociopaths to private venture firms. There’s Paul Angle’s history of Springfield up to 1860, Here I Have Lived, John Mack Faragher’s Sugar Creek, Paul Stroble, Jr.’s history of Vandalia from 1819 to 1839 he called High on the Okaw’s Western Bank and The Social Order Of a Frontier Community by Don Harrison Doyle, which is about Jacksonville. If you conclude from that list that historians think that nothing much interesting happened around this part of Illinois after the Civil War, you’d be right; a town, like a person, is usually never more interesting than in its youth.

Springfield might have inspired a new Paul Angle-type treatment – a Here the Rest of Us Lived, so to speak – that would have carried Springfield’s story forward from 1860s were not so much brainpower and money over the years diverted by, and to, the study of Lincoln. The real impediment is not subjects but money. Today there is an enormous appetite for oldfashioned narrative history in which the past is rendered as stories. Commercial publishing houses seldom try to feed that appetite, however, because the small size of the market means that sales can never be large enough to cover the costs. Academic historians usually are subsidized by fellowships or grants or the labors of graduate assistants, but they tend to focus on specialized topics or specific periods. Besides, storytelling tends to be disdained, as the guild these days favors data analysis.

That leaves local history to be written by amateurs. I mean no slur by the term. Springfield’s Benjamin Thomas, author of what was long considered the best one-volume biography of Lincoln, was an amateur. It is not the amateur’s status that is the problem. Rather, amateurs tend to be antiquarians fascinated with history because it happened in the past, while historians are interested because of what happened in the past. Also, amateurs tend to be local patriots who take up the pen out of enthusiasm. Enthusiasm will help one through the hard slog of writing it but it doesn’t often improve it.

In the end, the job requires deep reading and thinking that is beyond the grasp of those not trained in the discipline. Writing history is not quite the same as writing about history. Ask an opinion columnist and culture critic to write a history of the Springfield race riot, for example, and you will get something like Summer of Rage, the monograph on the Springfield race riots of 1908 that I wrote in 1973. The point in writing it was simply to announce to an unknowing city that the events of that August had happened. This would have been a piece of historical journalism I was capable of. Explaining the riots as well required more than I knew, with results that Roberta Senechal exposed as glib in her 1990 account, The Sociogenesis of a Race Riot.

A civilized city would provide the money to make it possible for serious people, amateur or professional, to do good work. Maybe crowdsource publication projects using the Web, a 2000s version of the old subscription model that paid for such works as John Carroll Power’s collection of old settlers’ tales. Or set up a local history district like a sewer or school district that levies a small tax to be used solely to pay for the research, writing and publication of serious works of local history, to jump-start historical preservation projects and the like.

Why should the taxpayers burden themselves with another special district? Here’s a quick answer. Think how useful it would be to a city facing problems such as economic development, public health or education to know which solutions are likely to work, and which ones are likely not to. Or to understand how social trends such as immigration are likely to affect it. Springfield does know – or would if it wanted to learn from its own past. The only thing new in the world is the history you don’t know, as Harry Truman famously said – including the history of what happens to societies when the history they don’t know is their own.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Editor’s note

Mayor Mike Houston’s call for privatizing Oak Ridge Cemetery was accomplished in the classic Springfi eld way. We can’t say for sure whether aldermen and the mayor were smoking cigars when they retired to a back room to jaw about a plan that would have lasting and serious ramifi cations for Abraham Lincoln’s permanent home, but they certainly deserve whatever clouds of suspicion now hang over an idea that should have been unveiled in the light of day, not the dark of a secret executive session. Trouble is, there doesn’t seem to be much recourse for those who take seriously the proposition that the public’s business should be conducted in public. Read about what happened when staff writer Bruce Rushton tried to fi le a police report on the mayor and aldermen, p. 11, see what cartoonist Chris Britt has to say about it, p. 4, and go online (www.illinoistimes.com) to learn more about the company that could soon be calling the shots at Oak Ridge. –Fletcher Farrar, editor and publisher