If you drive drunk in Sangamon County, you’re less likely to get caught than you were a few years ago. And you’re less likely to lose your license.

Since the early 1980s, lawmakers in the Land of Lincoln and throughout the nation have passed one get-tough law after another aimed at getting intoxicated drivers off the road. One of the most powerful punishments hit law books in 1986, when the legislature passed a statute mandating license suspensions when suspected drunken motorists either failed breath tests or refused them.

In theory, at least, the license suspension is automatic, regardless of what happens with the underlying DUI charge. The accused are entitled to hearings to contest suspensions, but all prosecutors must show is that police had a reasonable basis for demanding a breath test – bumping the centerline a few times, smelling like alcohol, swaying while talking to the cop and fumbling a bit while reaching for an insurance card is typically enough. And police often have videotape complete with sound so a judge can see exactly how a person was driving before the stop and behaving afterward.

In 2009, Illinois lawmakers made license suspensions even more onerous for suspected drunken drivers, who previously could drive on a limited basis with permits that allowed them to at least get to and from work even with suspended licenses. Under the new law, motorists whose licenses are suspended for either refusing or failing a breath test can drive anywhere they like, but only if they get ignition interlocks, installed at their own expense, that prevent cars from starting if drivers have alcohol in their systems. At the same time, lawmakers doubled the length of suspensions, which went from three to six months if a person failed a test and from six months to a year if a person refused to blow. No driving is allowed under any circumstances for the first 30 days.

The tough new law helped make Illinois a darling of Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which in 2011 gave the state a five-star rating, the highest possible. Just four other states earned five stars. MADD, which has pushed hard for ignition interlocks, also praised Illinois for highvisibility enforcement on the state’s roadways.

Less than two years later, however, cracks are beginning to show in the much-heralded crackdown, and Sangamon County lies at the epicenter.

Statistics from the secretary of state’s office show a huge increase in the number of suspected drunken drivers in Sangamon County who keep their licenses despite the law mandating suspensions. At the same time, the state is reducing grants to local police departments to pay for DUI enforcement.

It is a matter of money and priorities, say those who know the system best. And what constitutes justice lies in the eye of the beholder.

The hunt

“This just screams bogus insurance card,” says Officer Bob Jones of the Springfield Police Department as he pulls out his smartphone and goes to work.

The young man he’s pulled over for driving nearly 15 mph over the limit on North Fifth Street this Friday night has a freshly minted driver’s license that has just been reinstated after being suspended for prior traffic infractions. The accompanying insurance card looks just as new and has more flags than the United Nations.

For one thing, it’s laminated. For another, it’s good for one full year instead of six months, which is rare for someone with a poor driving record who’s piloting a mid-1990s Lincoln Town Car. And Jones has never heard of the Elephant Insurance Company.

No one answers when Jones calls the tollfree number on the card, but a Google search bears out the old saw: You do learn something new every day. It turns out that the Elephant Insurance Company really does exist. Jones still isn’t convinced that the card is legit but nonetheless cuts the quarry loose with a speeding ticket. Had there been an accident, Jones says, he likely would have issued a no insurance ticket and let a judge sort it out.

After a few minutes spent filling out a citation and a state form memorializing the stop, including questions about the driver’s ethnicity and whether a search was performed, Jones is on his way. He will spend an entire shift hunting drunks and come up empty except for a 19-year-old woman who admits drinking a wine cooler.

Minors with any trace of alcohol in their systems face license suspensions of at least three months under Illinois’ zero tolerance law for underage drivers, and so Jones hauls the woman to jail after she blows a .022 – well below the legal limit of .08 percent for a DUI charge – on a portable breath test, which isn’t deemed reliable enough to trigger a license suspension. At the jail, the woman sniffs and wipes away tears while awaiting a test on a more trustworthy machine.

She is lucky. Jones didn’t have the right paperwork on hand to conduct the test and had to wait for a state police officer to bring forms that include a written warning of the consequences for failing or refusing the test. By the time the forms arrive nearly an hour after she was pulled over, the alcohol in the woman’s body is gone. She registers a zero and keeps her license.

Jones, who has arrested more than 700

motorists during five years as a DUI enforcement officer, says that

it’s getting harder to find drunken drivers. His record haul is four DUI

arrests in one shift, but it’s not unusual to go two days without an

arrest, especially during the winter when folks tend to imbibe at home.

To

ride with Jones is to see firsthand the depth of cluelessness in the

motoring public. He travels the speed limit, but at least a halfdozen

drivers pass his marked car as he combs Springfield streets. Signaling

turns is passé and California stops are all the rage.

Figuring

out which traffic scofflaws are merely stupid and which are drunk is no

simple task. And so Jones skips the car with Georgia plates that barely

crawls before turning into St. John’s Hospital – likely someone not

familiar with the area. The woman who stays stopped when the light turns

green on Fifth Street looks promising, but it turns out she was busy

arguing with her boyfriend who was riding shotgun.

It is not as simple as pulling over everyone who breaks a traffic law.

“I always worry if I go after everyone for not signaling a turn, I’ll miss something big,” Jones says.

Tight money, quota questions

Jones may soon be a dinosaur.

The

state Department of Transportation, which pays Jones’ salary, is

cutting back on grants for DUI enforcement and plans to eliminate its

program that

pays for full-time DUI officers. The state has stopped paying for a

second DUI enforcement officer in the Springfield Police Department,

which has nonetheless kept that officer on drunk duty. In the future,

the state plans to pay for local DUI enforcement officers only around

holidays such as Christmas and Labor Day. It is, says IDOT spokeswoman

Paris Ervin, a matter of trying to save money.

The

grants have been a bargain for local law enforcement, according to

Chief Mark Gleason of the Leland Grove police department, who figures

that 320 hours of extra patrol time under a state grant costs his city

about $1,500, mostly for contributions to retirement plans that aren’t

covered by the state. It works out to $4.68 an hour, and officers on DUI

enforcement duty help fight all kinds of crime.

It’s getting harder to find drunken drivers.

“I always worry if I go after everyone for not signaling a turn, I’ll miss something big.”

“We average between three and five warrant arrests a year just doing the (DUI) details,” Gleason said.

Drunken

driving arrests could plummet with state cutbacks, judging by what has

happened since the Sangamon County Sheriff’s Office pulled its full-time

DUI officer from patrol last fall after the state said it would cut

funding from more than $100,000 to less than $60,000.

Between

Nov. 1, 2011, and Feb. 7, 2012, sheriff’s deputies filed 65 DUI cases

in circuit court. During that same period a year later, deputies without

state funding filed just 11 cases.

“We anticipated that happening,” says undersheriff Jack Campbell. “It’s just a matter of prioritizing our manpower.”

The

stats show that Deputy Travis Koester, who had been the county’s

designated DUI enforcement officer until he was reassigned last fall,

was a veritable machine when it came to busting drunks. Before being

reassigned, Koester

made one DUI arrest for every 2.11 hours of patrol, according to

reports submitted to the state Department of Transportation, which

requires officers to make one DUI arrest for every 10 hours of patrol as

a condition for receiving DUI grants.

That’s

not necessarily a good thing, according to attorneys who question

whether Koester was on a quest for pelts fueled by a quota.

“They

put a bounty program in writing,” says attorney Daniel Noll, who has

sued Koester and the county on behalf of two men whom the deputy

arrested on suspicion of DUI in separate incidents last year. “You have

to have so many citations and so many arrests. If that’s not a bounty

program, what is it?” In the lawsuit, Noll says that Koester arrested

more people on suspicion of DUI than any other officer in the state.

Prosecutors dismissed DUI charges against Timothy Ryan and Brandon

Hargrave, plaintiffs in the lawsuit filed by Noll, after judges

blistered Koester in open court.

In

Ryan’s case, Sangamon County Associate Judge John Madonia called

Koester’s testimony “convolutedly crappy” after the deputy could not

recall what he was doing when he first saw the defendant, then

questioned the accuracy of his own written report during a hearing held

to determine a license suspension should stick. The judge said that he

had not received “one iota of credible evidence” to justify the traffic

stop and subsequent arrest.

In

Hargrave’s case, Associate Judge Chris Perrin said a videotape showed

that the defendant passed sobriety tests that require a driver to

demonstrate balance, so the deputy had no reason to administer a breath

test.

Furthermore, Perrin

determined that Koester’s testimony differed from his written report

“and it leads me to believe that the guy is making it up as he goes

along.”

Attorneys for

the county deny the existence of a quota or a bounty program. Rather,

arrest numbers specified by the state grant are “objectives” as opposed

to requirements, the lawyers say in court documents filed in response to

Noll’s lawsuit. The lawyers say Koester did nothing wrong.

Deputy

chief Cliff Buscher of the Springfield Police Department rejects any

suggestion that the one-arrest-per-10-hours-of-patrol rule amounts to a

bounty program.

“I don’t consider it a bounty,” Buscher says.

“They

put that in there to ensure that we’re not paying someone overtime and a

salary to sit out there and do nothing for eight hours.”

Campbell

says there is no easy way to explain Koester’s arrest numbers. He

certainly had a zest. While other officers jailed suspects, Koester

sometimes cut them loose after impounding their cars and issuing notices

to appear in court, which allowed him to quickly return to patrol.

“I

know Deputy Koester was driven – he wanted to be the best,” Campbell

says. “Let’s not forget the fact that Deputy Koester might just have

been very good at getting DUI drivers. Sometimes, it’s just innate.”

License suspensions plummet

Numbers

vary depending on which agency does the math, but bounty or no,

statistics suggest that aggressive enforcement of DUI laws as well as

stricter statutes are making a difference.

In

1982, 968 people in Illinois died due to alcohol-related accidents,

according to the Illinois Secretary of State’s office. By 2008, that

number had fallen to 434. During that same time period, the percentage

of roadway fatalities related to alcohol fell from nearly 59 percent to

42 percent.

The state

Department of Transportation reports even fewer deaths due to drunken

driving. In 2006, IDOT says, 446 people died in accidents where at least

one driver was legally drunk; in 2010, that number had fallen to 298.

The percentage of traffic fatalities in which at least one driver was

drunk fell from 36 percent to 32 percent, according to IDOT.

Laws got considerably

tighter while the carnage lessened. In 1982, when nearly 1,000 people

died in alcohol-related accidents in Illinois, it was legal to drive

with a bloodalcohol content up to .10 percent; now, .08 percent is

legally drunk. Fines have skyrocketed. DUI statutes have become dizzying

as Illinois lawmakers since 1984 have passed more than 90 get-tough

laws that include a ban on being intoxicated while teaching kids to

drive and mandatory community service in a program benefiting children

for anyone convicted of DUI with a person younger than 16 in the

vehicle.

Bottom line, it’s way more likely that a drunken driver will end up in jail, lose their license

and pay sky-high insurance premiums if they get their license back than

it was 30 years ago, when states and the federal government started

cracking down.

That,

at least, is the public perception. But what really happens to a drunken

driver can vary widely in Illinois, depending on where the person is

arrested.

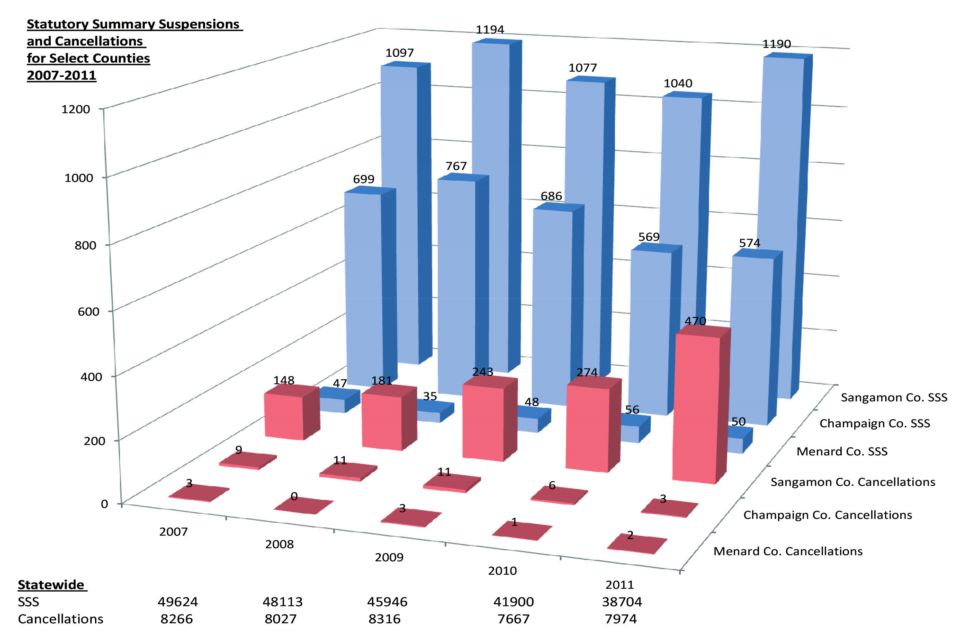

In Sangamon

County, statistics from the secretary of state show a huge increase in

the number of suspected drunken drivers who keep their licenses, despite

the law mandating suspension when someone either fails a breath test or

refuses to take one.

Five years ago, 148 of 1,097 motorists, or less than 14 percent of suspected drunken drivers,

set to have their licenses suspended in Sangamon County, convinced

either a judge or a prosecutor to throw out the suspension. The numbers

increased steadily so that 470 of 1,190 suspensions, or nearly 40

percent, were canceled, either by a judge or by prosecutors, in 2011.

Numbers for 2012 were not available.

By

contrast, no more than three of the 50 or so motorists arrested on

suspicion of DUI in Menard County in any given year keep their license,

according to Secretary of State data for 2007 through 2011. Champaign

County, where only 51 of the 3,295 suspected drunks arrested during the

same time period kept their licenses, is also a tough haul for the

drunken driver.

“We have to show that the

officer had reasonable grounds to believe that a defendant was

impaired,” says Menard County state’s attorney Kenneth Baumgarten. “It’s

not a very high standard (of proof). … I do believe there should be

driving consequences even for a first offender. I do believe that has a

deterrent effect.”

Around

the Sangamon County courthouse, defense attorneys say privately that

prosecutors use license suspensions as bargaining chips to extract

guilty pleas from first-time offenders when there is no accident or sign

of a high blood-alcohol content. Court supervision, which requires

defendants to plead guilty but isn’t reported to insurance companies, is

often granted in such cases. And first-time offenders constitute about

80 percent of the caseload in any given year.

Sangamon County State’s Attorney John Milhiser says that every case is looked at individually.

“It’s

a balance, in looking at these cases, at obtaining a plea of guilty on

DUI,” Milhiser said. “On some cases, it’s appropriate, in return for a

plea of guilty, that the suspension be rescinded.”

Despite

the high percentage of defendants who keep their licenses, Milhiser’s

office recently won high marks from Mothers Against Drunk Driving, which

analyzed DUI cases in nine Illinois counties handled between 2008 and

2012 and found that Sangamon and Kane counties were the only two where

at least 85 percent of cases ended with DUI convictions. Meanwhile,

Champaign County, where suspensions almost always stick, was judged less

effective because as many as 25 percent of DUI cases were dismissed,

reduced to lesser charges or ended with not-guilty verdicts, according

to the state-funded study conducted by MADD that used conviction rates

as the yardstick.

But conviction rates alone might not be the best measuring stick.

Without

a license suspension, a person convicted of DUI can still drive to

work, get their kids to school or whiz from one beer parlor to the next.

It’s that latter possibility that concerns MADD, which has pushed hard

for license suspensions that force even firsttime offenders to install

ignition interlocks as a condition for driving.

Trisha

Clegg, who works out of the Springfield MADD office and was project

manager for the study, says that MADD plans to look at license

suspensions but doesn’t yet have enough data to issue a report.

“Obviously,

MADD is a huge supporter of ignition interlocks,” Clegg said. “From

MADD’s point of view, we would be concerned about the number of

rescissions (of license suspensions).”

Mercy amid a crackdown

Daniel

Fultz, a Springfield defense attorney, says that the penalties have

gotten overly harsh for first-time offenders who aren’t likely to screw

up again. And a license suspension is a bigger loss than pleading guilty

and receiving court supervision, which often happens with first-time

offenders.

“People can

lose their jobs (without licenses),” Fultz said. “They can’t get their

kids to school. They can’t do anything. Springfield is a very spread-out

town – it’s not easy to get from one point to another. I do think, for

first-time offenders, losing your license is a much bigger issue to you

than pleading guilty and getting court supervision on a DUI. It doesn’t

have the practical effect on your life.”

Fultz

says prosecutors are taking a pragmatic approach. The system isn’t set

up to handle hundreds of license-suspension hearings that would result

if the state’s attorney’s office refused to drop license suspensions in

exchange for guilty pleas, he said.

“It would just be overwhelming,” Fultz said.

“The

system would absolutely collapse. … I think what you’re seeing is a

natural reaction to making the penalties so draconian they don’t work in

the real world.”

In

Menard County, where Baumgarten’s tough stance on license suspensions is

well known, the state’s attorney says that about 30 each year, or more

than half of DUI defendants, challenge suspensions despite the steep

odds against winning. Every challenge requires a hearing. It’s a

manageable number for a rural county like Menard, Fultz said, but sheer

volume makes Sangamon County different.

Regardless

of what happens in court, catching a DUI charge is expensive. The

Secretary of State pegs the cost at $16,580 if a defendant is convicted.

That figure, which includes $4,500 for increased insurance premiums and

$4,230 of lost income due to time spent in jail, community service and

court-ordered evaluations and classes on the dangers of drinking and

driving, sounds high to Fultz, who pegs the figure at between $6,000 and

$8,000.

Assuming

Fultz’s low-end estimate is correct, DUI is a huge industry in Sangamon

County, where between 1,000 and 1,200 people get arrested every year and

can be expected to spend more than $6 million on fines, lawyers,

impound fees, court costs, ignition interlocks, counseling and alcohol

classes. The government’s cut alone last year in fines, fees and court

costs was more than $1.5 million according to the Sangamon County

circuit clerk’s office and the figure has grown since 2008, when the

take was slightly more than $1.1 million. The typical fine for a

firsttime offender is $1,500 or more.

“A

guy who’s caught in possession of crack cocaine doesn’t pay that kind

of fine,” Fultz said. “The reason why the DUI laws are what they are, in

my opinion, is that they are a huge profit center for government.”

Buscher,

Gleason and Campbell insist that police don’t profit from busting

drunken drivers. Milhiser said that prosecutors work to keep the public

safe, not to generate money.

“DUI

cases are, historically, difficult cases,” Milhiser said. “They are

also very important cases. It’s dangerous for the entire community. We

take DUIs very seriously.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].