What was that again?

Hearing sometimes shouldn’t be believing

DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

Wait a minute Maybe my hears are clogged or somethin’ Maybe I’m not understanding the English language”

– “My Life Is Good,” by Randy Newman

I have concluded, after not very much thought, that books ought to come with warning labels. They should read, “Words in print do not necessarily sound the way they appear.”

I should explain. I learned almost everything I know except how to burn dinner from books. The people and places I read about were not discussed by the people around me, nor did I seek out the company of people who might have discussed them. As a result I “heard” their names with my mind’s ear, as it were.

And, like most autodidacts, I heard many of them wrong. I was for a time taken with the writing of Albert Camus. I knew he was French – the book covers said so – but I was no more capable of pronouncing a French surname than I was of cooking a French sauce. An older friend, then at university and thus privy to such secrets, corrected me. “Not ‘KAY-muss.’ ‘Ka-moo.’” Some 50 years later, I was consoled to learn that my fellow Springfieldian Robert Stuart Fitzgerald – poet laureate, Harvard professor, famed translator of the classics and starting quarterback at SHS – endured a moment much like that one when he was in prep school. A poem of his had just been published, which resulted in a faculty member admonishing him, “If you are going to be a writer you will have to learn that Goethe does not rhyme with Lethe.”

The incapable ear leads one astray as surely as the incapable eye. James Thurber once recalled a woman from the Middle West telling him about some legal involvement her daughter and sonin-law had got into. “I didn’t have the vaguest idea what it was all about,” he wrote, “and was merely feigning attention, when she ended her cloudy recital on a note of triumph. ‘So finally they decided to leave it where sleeping dogs lie.’” What Thurber called a “charmingly tainted idiom” is known to linquists (not at all charmingly) as an eggcorn. An eggcorn is created when you substitute a word or phrase with words that sound similar. An eggcorn differs from a malapropism in that the mangled phrase introduces a meaning that is different from the original but not obviously incorrect in context. In fact, the mangled phrase is usually plausible, if often a little antic. Common examples are “a tough road to hoe” or “antidotal evidence.”

Eggcorns litter the landscape. I found one the other day while reading about Washington, D.C.’s legal and political battle with a smartphone-dispatched town car service that the city regards as an illegal taxicab operation. “We’re trying to make it work for everybody,” said the chairman of the local taxi commission, “but we need cooperation. We can’t deal with an organization that sticks its thumb up our nose.”

I should think not. Thumbing its nose at the commission would be bad enough, but putting it up its nose would, at the very least, leave its members reluctant to shake hands on a deal afterward.

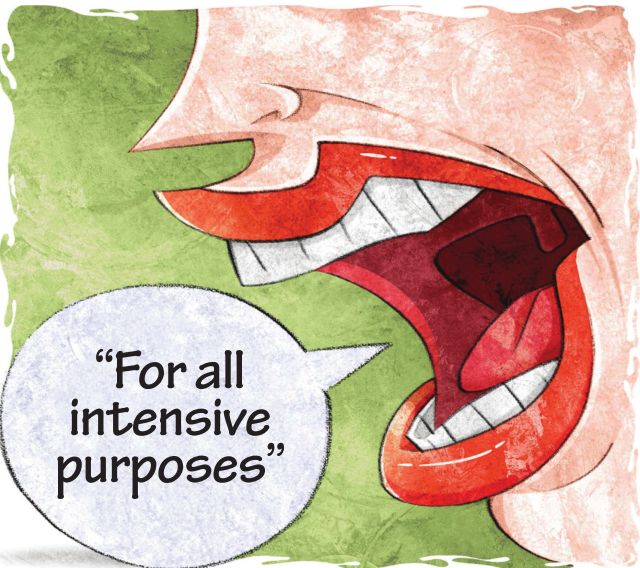

As this example proves, mighty confusions from tiny eggcorns grow. Another classic eggcorn is the phrase, “for all intensive purposes.” Paul Brians, emeritus professor of English at Washington State University, has described the substitution of the phrase for “all intents and purposes” as “another example of the oral transformation of language by people who don’t read much.” Brians, who seems likely to be one of those people who don’t get invited to parties much, added, “‘For all intents and purposes’ is an old cliché which won’t thrill anyone, but using the mistaken alternative is likely to elicit guffaws.”

Brians’ scorn drew this retort from one Alan Hazlett. “[I] was not embarrassed that I had spent too many years not saying ‘for all intents and purposes,’ but rather lamented the fact that ‘for all intensive purposes’ was not an expression in English. It seemed so well to capture what I meant when I uttered it – when we consider only those purposes that are intensive, that’s the sense in which this is a good idea. It’s a good idea for all intensive purposes, but not for some of your other purposes that aren’t so intensive.”

Amen, brother. I too used to say “for all intensive purposes” until I was corrected by a teacher of English in an icy tone she considered proper for such intensive purposes. I quit using the phrase after that rebuke, but think now that maybe I shouldn’t have. As Mr. Hazlett explained, the phrase makes sense – so much so that I’m hoping that “intensive purposes” spreads like wildflowers, in spite of the stings and arrows lifted against it by linguists.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].