No room at the inn

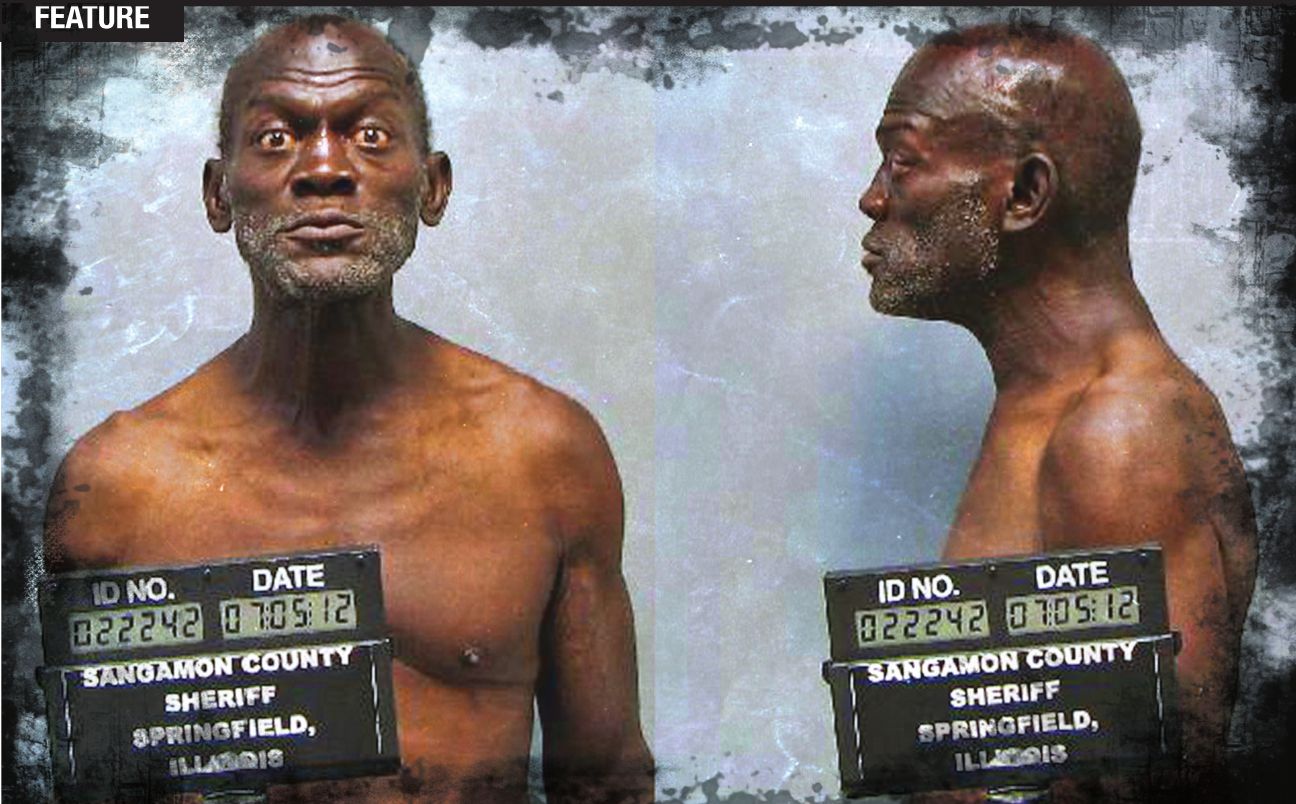

Alonso Travis died waiting for help

MENTAL HEALTH | Bruce Rushton

You may recall Alonso D. Travis, even if you never knew his name.

He was the guy who hit you up for money on downtown sidewalks and store parking lots along Jefferson Street and on North Grand Avenue. He got angry when you said no. He frightened people.

Was he dangerous? Folks who knew Travis on his worst days don’t leap to his defense. Put it this way: When Travis was feeling ornery, it was obvious, and people gave him wide berth. Sometimes that proved impossible, and so Travis became a regular at the Sangamon County jail, the repository of last resort for mentally ill people who are scary enough that they can’t be free and numerous enough that the system can’t help them.

Travis, 54, died Dec. 3 after he was found unresponsive in his cell. Everyone agrees that he didn’t belong in jail.

Declared unfit to stand trial on Nov. 15, Travis died on a waiting list five months after he was locked up, and there are still a half-dozen people in the jail who have been declared either not guilty by reason of insanity or unfit to stand trial due to mental illness. Some have been on the list for nearly two months, waiting for a bed to open up in the state’s stretched mental health system. And the trend isn’t promising.

Between 2009 and 2011, Illinois cut funding for the mentally ill by nearly $114 million, according to the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, which found that the cuts were the fourth-highest in the nation. While the state has been cutting, demand has been increasing for beds to treat people deemed unfit to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity. As of Jan. 1, the statewide waiting list stood at 98. A year ago, the backlog was 64; in 2011, there were 71 people waiting for beds. Five years ago, the number was below 50.

The waiting list has gotten longer even though the state in 2011 added 10 beds at McFarland Mental Health Center in Springfield. The state, which now has nearly 600 beds for people like Travis, hopes to add another 16 beds “in the near future,” but the outlook isn’t good, says Januari Smith, agency spokeswoman.

“An increase in court referrals combined with the state’s budget woes has made it difficult to keep up with demand for forensic beds,” Smith wrote in an email. “Without pension reform, the impact on social service agencies, such as IDHS, will be devastating.”

Meanwhile, both mentally ill inmates and jailers face the consequences.

Guards use restraint chairs, Tasers and pepper ball guns when mentally ill inmates fight, flood cells and otherwise misbehave. During the past six months, inmates have thrown trays, punched guards and eaten their own feces, according to jail records.

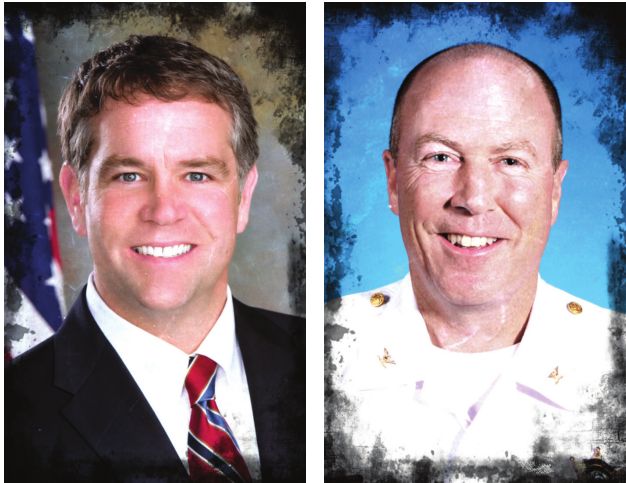

“We’re here to incarcerate criminals,” says Sangamon County undersheriff Jack Campbell, whose department runs the county lockup.

“Many of these people are just not criminals.”

Coronary atherosclerosis killed Travis; diabetes and high-blood pressure were contributing factors, according to an autopsy report. The report noted that Travis, who weighed 145 pounds and stood five-footnine, appeared older than his age, which isn’t surprising. He lived a rough life, and his case underscores the difficulties that face cops, prosecutors and jailers as both the mentally ill and cuts in services to help them just keep coming.

A lifelong history Born in East St. Louis on March 1, 1958, Alonso Travis had 11 siblings and a history of mental illness dating to age 10, when he was referred to a mental health facility after setting a boat on fire in St. Clair County.

He developed a drinking problem as a teenager, according to his mother, and that worsened mental problems that led to stays in mental institutions in East St. Louis in 1974, when he was 16, and in

St. Louis nine years later. Court records indicate that he was

hallucinating.

In the

early 1980s, Travis came to Springfield, where he received a diagnosis

of schizophrenia from the staff at a community mental health center. By

then, he had already been arrested at least seven times in at least

three states for such offenses as trespassing and disorderly conduct and

disturbing the peace and marijuana possession.

“ It’s troubling to me when someone is found not guilty by reason of insanity and they’re still

sitting in jail.”

A week after

receiving his schizophrenia diagnosis, Travis and another man broke into

a Springfield appliance store and stole two televisions. After three

months in jail, he pleaded guilty to burglary and was placed on

probation. Two weeks after walking out of jail, he was arrested for

shoplifting. Six days after that arrest, he was again arrested for

shoplifting.

He was not entirely out of control.

After

being placed on probation following his burglary conviction, Travis

attended classes at Lawrence Adult Education Center and met regularly

with his probation officer. While on probation, he sought help for his

mental problems at the St. John’s Hospital emergency room, which sent

him to the same mental health center that had diagnosed schizophrenia a

few months earlier. He was placed on a waiting list to see a therapist

after the staff concluded he didn’t need medication. He returned to the

center a few months later and said he needed a place to live. The staff

found no reason he couldn’t find a place on his own and sent him on his

way with a list of leads to check.

Court

records show that Travis turned violent in 1985, when he was jailed on a

misdemeanor charge of aggravated assault and felony charges of battery

and reckless conduct. One of the charges came after he threatened to

kill someone in downtown Springfield, either with a knife or by throwing

the person in front of a car. When he somehow came up with $500 and

bonded out of jail, Travis told his mother that he wanted to go to a

mental hospital, according to court records. Instead, he was arrested

the next day for shoplifting, and prosecutors moved to revoke his

probation.

At the

time, Travis was staying with his mother and other relatives when he

wasn’t in jail. He received $275 a month in Social Security benefits,

which he often spent on alcohol. In a court report, a probation officer

wrote that Travis seemed confused and might not know the consequences of

violating probation terms. A psychiatric evaluation found that his

biggest problem was alcohol abuse combined with “anti-social features,”

but he did not require psychiatric care.

“We

think that he is capable of understanding and holding responsibility

for his actions and behavior,” a social worker wrote. “He is definitely

capable of cooperating in his own defense with his attorneys.”

A

judge gave Travis another chance, keeping him on probation and ordering

him to get alcohol-abuse counseling. He was drunk when he showed up for

the first day of court-ordered counseling. After five days in a detox

unit, he slept through his first scheduled group therapy session, then

left the counseling center. He was soon back in jail on charges of

theft, shoplifting and resisting police. Three officers were required to

handcuff Travis as he struggled after he was caught stealing cosmetics

from a north end grocery store.

“It

appears he has no intention of becoming a law-abiding citizen,” a

probation officer wrote in a report to a judge who revoked probation and

sentenced Travis to three years in prison in the fall of 1985.

Prison

didn’t help. Less than two months after his release, police arrested

Travis after he was found in a Springfield parking lot threatening

motorists for no apparent reason. He kicked a stranger’s car in front of

an officer, then did it again while shouting profanities when the

officer told him to stop. Two officers took him to the ground while a

third put the handcuffs on.

This

time, Travis ended up at a mental health facility, according to court

records showing that the criminal case was continued in 1990 because he

was in McFarland Mental Health Center.

A

chance to live free Prosecutors dismissed a 1988 theft charge against

Travis because he was in Chester Mental Health Center. Then he

disappeared from the public record in Sangamon County for more than two

decades, with no police encounters, criminal charges or courtroom

appearances. There’s no way of knowing whether he was civilly committed

to a mental institution, because commitment proceedings are

confidential.

Jeremiah

Elugbadebo, who runs a group home in Enos Park, says he picked up

Travis and two other men from a Jacksonville nursing home in 2010. It

was a secure setting, Elugbadebo says, and Travis was not free to leave.

Springfield would be different. Travis would live in the community, and

the state would pay Elugbadebo $500 a month for food and rent.

Elugbadebo remembers Travis as a man who behaved himself and enjoyed

oatmeal for breakfast – at least, in the beginning.

“It’s

part of deinstitutionalization – get them out of nursing homes,”

Elugbadebo said. “This is where the doctors feel he can come. He did OK

at first.”

That soon

changed. A long string of arrests began in May 2011, when Travis

followed a couple into their home after they told him from a porch that

they would not give him a cigarette. He was arrested the next day for

shoplifting a 60-cent package of ham from the Shop ‘n Save on North

Grand Avenue. Two days later, he returned to the store to

panhandle in the parking lot and was arrested for trespassing. He was

arrested more than a half-dozen times for either shoplifting or

trespassing at Shop ’n Save during the ensuing year, and plenty of other

businesses also called 911 to have Travis removed.

All

told, Springfield police arrested Travis more than 50 times in barely

more than a year. A manager at McDonald’s at the intersection of North

Grand Avenue and Ninth Street called police one morning last May when

Travis showed up, demanding that customers give him 10 dollars and

shouting for employees to give him free food. Last June, he unzipped in a

north end parking lot and urinated in full view of passersby and a

Springfield police officer who was parked in the lot. He lunged toward a

woman near the Old State Capitol when she wouldn’t give him money.

A

stick-up attempt last February was absurd. Travis walked into a

check-cashing store on Sangamon Avenue and said he was robbing the place

because he needed 50 cents for bus fare. When the manager wouldn’t give

him anything, Travis grabbed a handful of pens from the counter, then

left. Police arrested him about a block away and found that he had $1.50

on him. The officer who read Travis his rights wasn’t sure that he

understood them.

“Alonso is very mentally limited if not retarded,” the officer wrote in his report.

Travis

also had diabetes, and irrationality often coincided with low blood

sugar, Elugbadebo recalls. Through it all, Travis was infatuated with

the lottery, buying tickets that he didn’t throw away even after losing.

A gas station near the group home where he lived became a magnet after

selling Travis a $200 winning ticket.

“He

goes there constantly to buy lottery tickets,” Elugbadebo recalls.

“Then he wasn’t winning, and he got mad. He would run out of money

quickly.”

It was a

matter of not being accustomed to freedom, according to Elugbadebo, who

says that Travis went from a $30 per month allowance in the Jacksonville

nursing home to a comparative windfall of $50 a week when he moved to

Springfield, where he took to drinking and bringing home spoiled food

and old clothing that he found in garbage bins.

“He needs proper supervision,” Elugbadebo says. “He can’t live on his own.”

Travis

wasn’t allowed to live at the group home after the fall of 2011, when

police were called after he choked and battered other residents. He

moved into a house on North MacArthur Boulevard with a brother who has a

longer court record than he did, but that didn’t go smoothly, either.

Police were called at least once after the brothers argued, with

officers taking Travis to the Washington Street Mission to keep the two

separated.

Ken

Mitchell, director of the Washington Street Mission where Travis became a

regular, said that other people at the mission learned to avoid him.

Mission denizens usually don’t have much money, Mitchell says, and so

folks swap things – a cigarette, for instance, in exchange for carrying

someone’s bag. Travis usually brought two sacks to the mission, one

filled with cigarette butts, the other with scratchedoff lottery

tickets, that he would try to barter for things of value.

“He

was always kind of confrontational – he was in people’s face pretty

often,” Mitchell recalls. “People here generally understood that.”

Shirley

Fitzgerald, a clerk at Springfield Novelty and Gifts, said that Travis

proved a pest after she gave him $2 in the winter of 2011 against her

better judgment. He kept returning to the downtown store, usually to shoplift, and she learned to

telephone other shopkeepers when she saw Travis heading in their

direction.

Fitzgerald

always shooed Travis away on her own until she caught him stealing

several decks of playing cards last June. After he turned over four

packs of cards, he offered to let Fitzgerald conduct a pat-down search.

He walked off while she called police, and officers arrested him a few

blocks away near the courthouse. She said she never feared him.

“His bark was a little worse than his bite,” Fitzgerald said. “I’d had my fill.”

But

Travis could be scary. Last March, Travis walked into Hardee’s on

Jefferson and pulled a knife on a manager who confronted him. While the

manager called police, Travis went to a neighboring McDonald’s, where he

began panhandling and stealing salt and pepper shakers from tables.

When an employee told him to stop, he again pulled the knife and pointed

it at her, prompting a scream as he turned and walked out. Police

arrested him in the parking lot. Over the objection of prosecutors who

wanted to ensure Travis would be locked up, Sangamon County Circuit

Court Associate Judge John Madonia set bond at $10,000.

“ We’re here to incarcerate criminals.

Many of these people are just not criminals.”

“We believed he

needed to be in the Sangamon County jail to protect the public,” says

John Milhiser, Sangamon County state’s attorney. “Our jails are full of

individuals who might be better helped in a therapeutic setting.

Unfortunately, there are not enough beds available for these folks in

state hospitals or in other areas, so they end up being housed in the

Sangamon County jail. They have to be to protect the public.”

After

a month in jail, Travis pleaded guilty to misdemeanor assault charges

and was freed, only to be jailed three days later for trespassing at

Shop ’n Save.

“A vicious cycle” The last arrest came on July 5.

It

wasn’t yet 8 a.m. when Travis got into an altercation with a homeless

man at the Washington Street Mission. When Mitchell escorted him to the

door and told him that he couldn’t return for a month, Travis suddenly

turned and struck the mission director in the face. It seemed like an

impulsive act.

“I think that he was surprised, too,” says Mitchell, who was not injured.

Travis was gone when police arrived.

He

surfaced five hours later when the manager of a dollar store on North

Grand Avenue called police because Travis punched him in the face after

being told to leave. He was arrested and charged with misdemeanor

battery.

This time,

the jailhouse door didn’t revolve. After nearly a month in jail, Travis

started acting up in a serious way. Prosecutors charged him with a

felony after he spat on a guard in early August. Campbell says that he

bit another guard, who needed seven stitches, and threw a tray at

another, who suffered a concussion. He also plugged his toilet to flood

his cell and threw garbage around a common area.

“Starting in August, we begin to have this series of infractions,” Campbell says. “He hurt several of our people.”

A

judge ordered a psychiatric evaluation in mid-August, but Travis did

not otherwise see a psychiatrist while in the jail, Campbell says. While

Travis got the best care the jail could provide, Campbell says, that

doesn’t mean that he was in the right place.

“We

are not set up to handle these people,” Campbell says. “It causes us a

lot of issues. They fight with our staff. They injure themselves, and

now we have to take them to the hospital for treatment. It’s a vicious

cycle. There’s really nothing you can do with them. Nothing takes – it just goes in one ear and out the other.”

On

Nov. 13, guards found Travis in his cell with a mouth full of

Styrofoam, likely from a disposable cup, Campbell says. Two days later,

prosecutors and a court-appointed public defender agreed: Travis, who

had been in jail more than four months, was not mentally fit to stand

trial and should be sent to a state mental health facility to regain his

sanity.

But there

wasn’t room for Travis in state facilities and so he was placed on a

waiting list after a judge signed an order for treatment. Five days

later, jailers called the state Department of Human Services, which runs

the state’s mental institutions, and said they were concerned about

Travis.

It’s

not clear what triggered the call to DHS. Documents released pursuant

to a Freedom of Information Act request made to the jail don’t include

medical records. Smith, the DHS spokeswoman, said that she could not

discuss individual cases. After visiting with Travis, reviewing his

medical records and speaking with the jail’s medical staff, a DHS

employee on Nov. 21 told jailers that it was “apparent” that Travis

needed to be moved up on the waiting list, according to a Dec. 5 memo

written by a jail sergeant two days after Travis’ demise.

Jailers

grew concerned when Travis didn’t eat his lunch on Dec. 3. A guard

reported that he appeared to be sleeping. The guard was concerned enough

that he and another guard monitored Travis’ camera-equipped cell from a

control room. He was lying on the floor and didn’t respond when a guard

tried speaking with him shortly before 3 p.m.

“I could see that he was breathing but he didn’t look good at all,” the guard reported.

Jailers

pulled Travis out of his cell and called 911. Doctors at St. John’s

Hospital pronounced him dead at 3:37 p.m., about 20 minutes after he

arrived at the hospital. He died facing no fewer than four lawsuits from

the City of Springfield filed after he failed to pay fines after

receiving tickets for misdemeanors including aggressive panhandling,

trespassing and drinking in public.

Who’s

next? With Travis gone, a half-dozen inmates in the county jail deemed

unfit to stand trial or not guilty by reason of insanity are now on the

waiting list to get into mental health facilities. Christopher Maggio,

for example, has been on the list for more than a month after being

found not guilty by reason of insanity. He had been charged with

battery.

Maggio’s

victim was an employee at McFarland Mental Health Center whom he hit

during a struggle to medicate him more than a year ago. After eight

months of treatment in state mental health facilities, he was found fit

to stand trial on Sept. 6 and sent to jail. After less than three weeks

of being locked up, his lawyer had doubts about his sanity and so Maggio

underwent a psychiatric evaluation and was found “marginally fit” to

stand trial. Sangamon County Circuit Court Judge John Belz found him not

guilty by reason of insanity on Dec. 18, and Maggio has been waiting to

be sent back to a mental institution ever since.

“It’s

troubling to me when someone is found not guilty by reason of insanity

and they’re still sitting in jail,” says Sangamon County public defender

Robert Scherschligt, Maggio’s lawyer. “The demand for mental health

services is increasing, yet the facilities and services are decreasing.

“That’s a problem, in my opinion.”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].