Megaminds

The search for the world’s best memory athletes

SCIENCE | Jessica Lussenhop

A man in a fedora walks into an empty classroom on the second floor of a building on Washington University’s campus and waits in the darkened room. He has never been here before – not to this classroom, not even to St. Louis.

The professor arrives and flicks on a light.

Soon students dressed in the 8 a.m. class uniform of track pants and sweatshirts begin to trickle through the door. As each enters the room, the fedora man walks over and introduces himself with a handshake. Before long the entire room is a din of chatter and tapping laptop keys. There are roughly 40 students assembled.

The professor asks for their attention. But instead of beginning his lecture, he steps back, and the man in the fedora stands up.

“Hi, everyone. My name is Chester Santos. I am the 2008 USA National Memory Champion,” he says, walking to the front of the room. “If you remember meeting me when you walked in today, if I shook your hand, gave you my name, got your name, if you remember that happening, please stand up.”

Chair legs scrape as the majority of the room rises.

“John?” Santos asks, pointing to a shaggy student closest to the far wall.

John nods and sits. “Charlotte,” Santos continues, starting with the girl at the front of the row next to John. He goes to the boy behind her, “Dan.”

This story was originally published in Riverfront Times, St. Louis’ news and arts weekly. An abridged version is reprinted here with permission. Copyright Riverfront Times 2012.

Santos starts to pick up speed. “Helene. Sophie. Keisha. Vivienne. Nick.

Jackie. Ashley. Prateek. Ashley. Ben. John. Neil. Huh,” he pauses at an Asian girl about halfway through the room. “I’m not 100 percent positive on you. I’ll come back.”

He continues: “Alec. Shane. Isaiah. Rohit.

Marlow. Emily. Laura. Deena. Talia. Jeremy. Moe. Anna. Reggie. Jessica. Wayan. Gaithree. Rosie.

“And then you,” he says swinging back around to the lone girl standing in the middle of the room, “it’s Kim.”

“Yes,” she nods. “Wow,” someone murmurs, and the room breaks into applause.

After meeting them for mere seconds – jetlagged and not necessarily in the best “memory shape” of his life – Santos correctly names 33 students. In the past he’s successfully made it through an auditorium of 200. It’s not just a quick one-off, either. As the floor opens up to questions, he calls on each person by name.

The year he took the title, Santos memorized a 135-digit sequence, and studied and recited the order of a pack of playing cards in a minute and 27 seconds. At a public event in March, he named all 535 men and women of the U.S. Congress as well as their district number.

“I’ve gotten better and better and better,” he tells the students.

After the demo is over, Santos’ handler walks him down a flight of stairs and outside toward the Psychology Building next door, where for the last three days he has been through a battery of tests designed to unlock the secrets of his brain. Some of the challenges feel familiar – recognizing names and faces, memorizing word lists – but others are intended to probe his limitations.

“My prediction,” Santos says, confident after his second day of testing, “is we’re still going to perform above average.”

By

“we,” Santos is referring to his fellow “memory athletes.” In the

United States there are roughly 50 active competitors, called “MAs” for

short; in places like the United Kingdom, Germany and China there are

hundreds more. In meets all over the globe these men and women converge

to outthink one another in a series of mental tasks designed to test the

limits of human memory capacity. Records are broken at these events

every year; some believe the brain’s powers of recall are limitless. But

if there is a ceiling, the memory athletes will hit it.

He doesn’t know it at the time, but Santos’ boast about his fellow MAs turns out to be prescient.

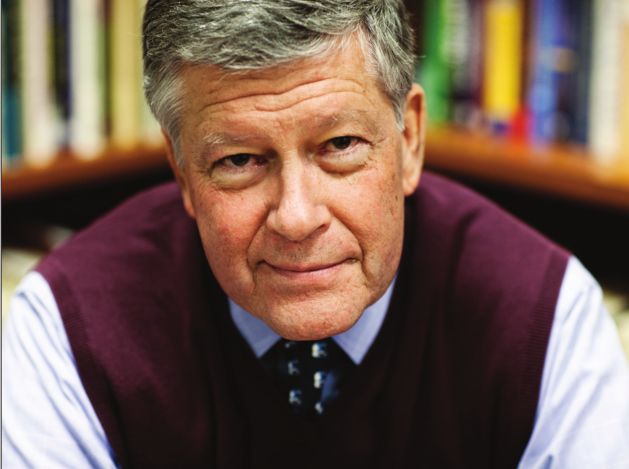

“These

people are just remarkable,” says Henry “Roddy” Roediger III, a doctor

of psychology, who, as part of Wash. U.’s Superior Memory Project, has

invited the world’s foremost megaminds to St. Louis. “Almost every test

we give the memory athletes, even though they’ve never taken these tests

before.... They do better.”

TEST IS BEST

Roediger

– a more-salt-than-pepper-haired 65-year-old with a slightly crooked

smile – rose to prominence in the 1990s when he entered the infamous

“memory wars” at a time when therapy patients all over the nation were

acquiring “recovered memories” through controversial techniques such as

hypnosis. Visions of horrific sexual abuse and Satanic rituals were

assumed to be true. Dozens of cases went to court. The “Satanic panic”

died down after investigations proved in some cases that the abuses

couldn’t have happened. Roediger influenced the conversation by showing

that if given a list of words (bed, rest, awake, tired, dream), subjects reported they’d seen related words that never appeared on the list (such as sleep or slumber).

The finding proved that it was possible to create false memories.

“That

is among one of the most widely cited works in the field of memory,”

says Elizabeth Loftus, a professor of law and psychology and a memory

expert at University of California-Irvine. “He is a master at designing

and conducting experiments.”

In

the last 10 years Roediger’s research into the “testing effect” proved

that – as unpopular as the notion may be with students – repeated,

low-stakes test-taking helps pupils retain information better than

simply “studying” the material for the same amount of time. The theory

played out when Roediger and his students implemented it in seventh- and

eighth-grade classes at Columbia Middle School in Illinois.

“What

he’s found is, the best way to make a memory is to retrieve the

information. It has enormous practical implications,” says James

McGaugh, a neuroscientist and superiormemory researcher at UC-Irvine.

“It’s solely his discovery.”

Now

Roediger, his frequent collaborator Kathleen McDermott, and David

Balota, a cognitive-psychology professor at Wash. U., hope that studying

memory athletes will unravel what Roediger believes could be a

particularly helpful form of superior memory – one that’s conceivably

accessible to anyone.

“We

hope, by studying how it succeeds, that maybe all of us can improve our

memories,” says Roediger. “Hopefully we can find some things that help

in remediating memory for people who have impaired memory.”

Memory workout

Nelson Dellis will never forget the two of hearts and the ten of diamonds.

Sitting in the hot seat onstage in the final round of the USA Memory Championship in 2010, Dellis appeared collected.

To his left sat the defending champion, and next to him, the 2005

titleholder. All that separated Dellis, a lanky, six-foot-seven-inch

University of Miami graduate student, from the championship were two

packs of playing cards.

The

competitors had survived a gauntlet of memory tasks in order to get to

this point. That morning they were tasked with memorizing 117 faces and

names, a list of 500 digits, 100 words, a previously unpublished poem

and the order of a deck of cards. Dellis had already bested both of his

final competitors in speed numbers and memorizing cards. He figured he

had it in the bag.

For

the final event all three men memorized the same two decks and were

about to take turns in a sudden-death elimination challenge, naming the

order of the cards one at a time. Dellis went first.

“Ten

of diamonds,” he said confidently. There was a tiny silence. One of the

other memory athletes shook his head, making a “cut-it” motion with his

hand.

“Nelson, we’ve got two of hearts,” the moderator responded.

Dellis’

eyes flew to the moderator, then to the ceiling. He’d named the last

card in the deck, not the first. As the round proceeded without him, he

looked into the audience and smiled mirthlessly at his girlfriend.

“Everyone who was supporting me was really disappointed,” he recalls. “I thought I was going to win.”

The experience highlights another trick of human memory – we recall tragedy better than triumph.

Though as a spectator sport the USA Memory Championship leaves

something to be desired, this is where superior memories are forged.

Most memory athletes swear that anyone can do what they do and, though

highly competitive, they’re willing to share their tricks.

The lessons, however, can be awkward.

Seated

in the lounge of Wash. U.’s Olin Library, Santos cringes slightly when

this reporter presents him with a photo of a female and asks him to

explain how he would remember the woman’s name.

“You’re not going to tell her, are you?” he asks.

The

woman in the photo is named “Dana,” and after a quick glance – Santos

says he needs about five seconds to lock in a name with a face – he has

it.

“OK, so, when I

saw her, first thing that came to my mind is that she has a pretty long

pointy nose,” says Santos. “So you want to exaggerate it and see it as a

really long nose, and I’d stick a Danish to it.”

The

Pinocchio nose spearing a Danish would likely be enough for Santos to

get “Dana.” But if he needed some extra help he might envision an apple

exploding out of the Danish dangling from the tip of the nose – a

reminder of the final ‘a’ sound in “Dana.”

“Next time I see her I would immediately notice the nose, and all that crazy imagery comes back to me,” he says.

Earlier

that same afternoon, Brad Zupp – a wiry, bespectacled Upstate New

Yorker who works as a full-time juggler and magician – paints a

similarly graphic tableau for memorizing playing cards. He’s fond of a

technique called “person-action-object,” which allows him to remember

groups of three cards in short sentences.

Zupp’s wife is using a scissors to excitedly open a Christmas present.

This

sentence corresponds to the queen of hearts, three of clubs and ace of

spades. Zupp has a person or a character assigned to all 52 playing

cards. Like many memory athletes, the queen of hearts is someone of

great emotional significance – his wife. He’s assigned his hairdresser

to the three of clubs (signified by scissors) and Santa Claus to the ace

of spades (represented by the present she’s ripping apart).

“They’re

pictures, so I don’t have to keep thinking about them to keep them

there,” he explains. “I’m not using repetition, I’m using images and

picturing them and making some really silly and creative associations.”

These

mnemonic memorization systems are well known to Roediger. He likes

using a primitive one to psych out his students by flawlessly

memorizing, after just one try, a list of 20 words forward and backward

on the first day of class.

“That really blew people’s minds,” he says. “The tricks are ancient. The Greeks and Romans knew about them.”

In 2002 a brain-imaging study done on competitors from the

World Memory Championship in London showed no physical differences in

the memory athletes’ brains, though some areas associated with

navigation lit up as they interpreted information as pictures and

scenes. This seemingly bolsters the memory athletes’ insistence that

anyone can do what they do, but the researchers want to know more.

“First

what we have to do is have a good cognitive profile of these

individuals,” says Balota. “Is it the case that they just have general

better cognitive skills, or is it the case that they’re really truly

outstanding consolidators?”

Can anybody do it?

There

are no MRI scanners or cranial electrodes in the cognitive lab on the

third floor of Wash. U.’s Psychology Building, only a basket full of

mini Twix bars at the front desk and a row of private rooms with

computers.

The MAs are put through

three days of testing, much of it consisting of staring at monitors.

Though Roediger is still far from having publishable data, striking

results are already emerging from just a quick glance at the test

results of five memory athletes, including Santos, Zupp and Dellis.

In

one test, called the Stroop Color-Word Test, the mental athletes are

shown a list of words in a colored font. When a word is printed, for

example, in green ink, but the word itself says “red,” most test-takers

show some amount of “interference.” They’re tripped up by the word and

answer incorrectly when asked what color the word was written in.

Conversely, if a neutral word like “chair” is written in blue ink,

there’s no trouble at all in naming the correct color.

The memory athletes, however, do not appear to fall for this trap.

“They show about half as much interference in the color-word test,” Roediger says.

The

tasks also reveal that the athletes’ memories are not superhuman, nor

somehow “photographic.” In another test, the athletes memorize

“non-words” – pure gibberish. The researchers asked this reporter not to

reprint the exact words found on the task, but imagine trying to

memorize these words: flerp, conternsta, utopare, yerf, orniga, palkemf.

Most people just give up. And at first, the memory athletes do about as poorly as average test takers.

That

is, until they’re presented with a list like that again. Some of the

athletes reported that they switched strategies. Dellis boasts that on

his test he invented meanings for the words – as if composing the

fictional Game of Thrones language Dothraki on the fly. And it worked.

“That

was really hard,” says Dellis, who, after that devastating loss at the

2010 USA Memory Championship, came back to win it in 2011 and is now the

two-time reigning national champion. “Everybody has a very steep dip in

the scores for that. Mine were still pretty good.”

Though

the results are far from definitive, K. Anders Ericsson, a Florida

State University cognitive psychologist who’s been studying memory

athletes for decades, found it similarly difficult to “interfere” with

the memory of Chao Lu, the man who holds the world record for memorized

digits of pi (a staggering 67,890), by setting up tests intended to

distract or interfere with his mnemonic concentration.

“These manipulations,” Ericsson wrote, “did not reduce Chao Lu’s virtually perfect accuracy of recall.”

It

is promising results such these that are an endless source of

frustration to the memory athletes and the founders of the USA Memory

Championship: The techniques they espouse aren’t taught in schools.

“If

you can get into this and do it through high school and college and

through law school – if I would have known it back then, it would’ve

changed my life,” says Dellis. “I think it should be taught to kids, for

sure.”

But Ericsson

does raise an important point. “From my experience, people who would be

interested in training their memory are not your average person,” he

says.

Roediger puts it

even more bluntly: “You’re not going to take somebody who’s kind of a

dullard – they’re not going to be memorizing a deck of cards in 24 and a

half seconds.”

Whether

or not the memory techniques can truly soup up the mind’s faculties is a

question that a second phase of Roediger’s project could attempt to

answer, using students. There is talk within the Superior Memory Project

team of starting a freshman seminar in fall 2013 that would not only

teach about the way mnemonics work, but attempt to turn its participants

into the next generation of memory champions. The researchers would

then track the students’ academic progress for the remainder of their time at Wash. U.

“We’d

compare them to other freshmen who are taking random [seminars]. We’d

measure them all beforehand and make sure there’s no difference,”

Roediger says. “It’s a natural experiment. We can just follow my 20, or

however many, from my freshman seminar. Do they make better grades?”

Memory mountaineer

In his

stately office, the bookshelves piled to the ceiling with titles

promising to improve one’s memory, Roediger concedes he’s noticed signs

of his own memory faltering.

“I

do have name-finding difficulty. That’s the first thing to go in older

adults,” he says. “Strangely, it is restaurants. I’ll say, ‘Let’s go to

somewhere.’ I’ll have it perfectly envisioned in my mind and then not be

able to come up with a name. It’s annoying.”

This

is, of course, where the two disciplines of studying memory success and

memory failure meet. The dream would ultimately be to save us from, not

just the day-to-day perils of forgetting to buy milk or putting a

toilet seat down, but from memory deterioration due to accidents,

illness and age.

Roediger

doesn’t get sentimental about his own memories, nor grandiose about

whether his research will be able to stave off his or anyone else’s

memory loss. As for the memory athletes themselves, their ambitions for

their skills range quite a bit.

Roediger

doesn’t get sentimental about his own memories, nor grandiose about

whether his research will be able to stave off his or anyone else’s

memory loss. As for the memory athletes themselves, their ambitions for

their skills range quite a bit.

Brad

Zupp incorporated teaching the techniques into his act long ago, with

the hope that kids who struggle with rote memorization in school will

find his methods helpful. Chester Santos bills himself as “The

International Man of Memory” and travels the globe giving talks to

corporations and business leaders on how to make flawless presentations

without notes, or remember important people after just one meeting.

Nelson Dellis does one-onone coaching and is the spokesperson for two

memory-related companies (health supplements and data servers), but

dreams of one day being commissioned by professional sports teams to

help, say, a new NFL quarterback memorize his Bible-thick stack of

plays.

He has also

started a charity that marries his two passions – memory training and

mountaineering. It’s called Climb for Memory, and it seeks to raise

awareness and funds for studying Alzheimer’s. As he has often remarked,

Dellis began pursuing memory training in the first place because of his

own grandmother’s descent into dementia.

“I wanted to see if there was anything I could do for my own mind,” he says.

Roediger

says there’s a controversial theory that supposes that building up

one’s skill as a memorizer, or “cognitive reserve,” could stave off the

outward signs of dementia – that it’s worthwhile to be an ant

stockpiling brain cells for winter while the rest of the grasshoppers

sing. But it’s totally unproven and, as of today, none of the world’s

memory champions is old enough to prove that their cerebral stockpile is

keeping them free of dementia.

Roediger

sounds skeptical but cautiously open-minded to the idea that Dellis, or

anyone else, could save himself from such a fate.

“That would be the great hope,” says Roediger. “Maybe he will. Nobody knows.”

Jessica Lussenhop is a staff writer at the Riverfront Times in St. Louis; previously she held that same position at City Pages, RFT’s sister paper in the Twin Cities. Find her on Twitter @ Lussenpop.