Flatland into flatscapes

Scenic paintings of the central Illinois landscape. Really.

DYPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

Earlier this year, a young English woman named Jennifer Bradley undertook, with friends, to run across the U.S. in 80 days. She thus became the first British woman (we are told) to cross the country on foot, which is the sort of thing that the Brits tend to do with their time now that they no longer have a empire to run. Anyway, she was asked by a newspaper reporter back home if she ever had doubts about the wisdom of undertaking this magnificently pointless trek. Yes, a couple, she said. One was when she was injured and had to walk for several days in pain. The other was later, when she became “pretty bored with the endless cornfields and cattle farms in Iowa and Illinois.”

You knew she’d say that, didn’t you? What Ms. Bradley did not know is that there is plenty of Downstate Illinois scenery worth looking at. The problem is that it isn’t visible from the roadsides, but only in the area’s galleries and building lobbies. This usually surprises people. What is merely boring for land-bound travelers like Ms. Bradley poses real dilemmas for the painter of outdoor scenes. The picturesque is what sells, and the picturesque has long meant mountains and trees of which central Illinois has none and few, respectively.

Picturesqueness can be in the painting even if it’s not in the subject. Hedley Waycott, English-born and self-taught, on either side of World War I painted the Illinois River valley in the American Impressionist style, which is to say he rendered such scenes generic, pretty, inoffensive and instantly forgettable. Another area Impressionist is Robert Root. He studied in St. Louis and then Paris before returning to his native Shelbyville (!) in the latter 1890s to open a studio. Among his work are pleasant if unremarkable portraits of the local landscape such as 1918’s “Shelbyville on the Kaskaskia.”

More recent painters have been technically more accomplished and artistically more interesting. Billy Morrow Jackson, who taught for years at the U of I in Urbana, was among the first of a wave of contemporary painters and photographers who found a subject in the Grand Prairie beginning in the 1970s. Some 50 miles up I-74, in Bloomington, Harold Gregor was doing similar work. The former is often classed as a latter-day American Luminist, while the latter was part of the photo-realists’ reaction in the late 1960s against Abstract Expressionist dogmas.

In the 1980s we saw works from James Winn, a former student of Gregor who grew up in Metamora and made his home in Sycamore. In the 1980s George Atkinson, born in Springfield and educated in San Francisco, used pastels to render scenes from the landscape that lies mostly within a short drive from Springfield. Jackson tended to concentrate on farmsteads, Gregor on agricultural landscape, Atkinson and Winn on skyscapes. (Atkinson has since switched from countryside to country people in the persons of dairy farmers and their farms.)

The works of all three was painstakingly rendered so as to make their images realer than real, as one curator put it, with a clarity at every point of perspective unachievable by the eye, even (on this scale) the camera. In that sense there is more to see in the paintings than there is in the landscape itself, especially since most of us “see” the central Illinois landscape from passing cars, from which everything that might interest the eye is a blur. No wonder these works were revelations when they debuted.

That was 25 years ago. These three didn’t exhaust the aesthetic possibilities of the subject, but like so many artists they might have exhausted their understanding of it, or perhaps their interest in it. That in itself is not a problem; I don’t mind if a painter gives us the same pictuire over and over, if it’s a good picture to begin with, and these were.

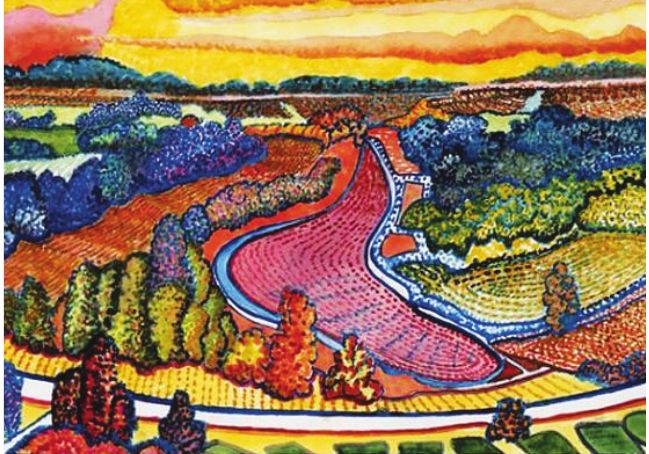

Still, I remember hoping their example if not their technique would excite new painters to attempt to show us their versions of Ms. Bradley’s endless cornfields. It did – his name is Harold Gregor. As I noted in “Living in three dimensions,” (Aug. 19, 2010), reading a landscape as flat as central Illinois’ from ground level is like trying to read a book while peering at it from the edge of the page. Gregor got around that by rendering Illinois’ agriculturalized landscape as seen from the air. Among the results are his “Flatscapes,” aerial views of farmsteads rendered in colors that will be familiar to kids who ever tripped out while hitchhiking home from the U of I.

Most recently Gregor’s work – he’s now 83 – has blossomed into color abstraction in his “trail paintings” and “vibrascapes.” It might be fun to explore why his landscapes become more interesting as they grow less recognizable. For now, I just want to say that if anyone wants to know what to get me for Christmas, I have a gallery I’d like to put you in touch with.