AFSCME under siege

Union faces unprecedented challenges, even from allies

LABOR | Patrick Yeagle

What would drive a crowd of unionized state employees to boo the very governor they helped elect? The answer is about $83 billion of pension underfunding, a broken labor contract and a lot of jobs in jeopardy.

When Gov. Pat Quinn stood before a crowd of fellow Democrats and union members on Governor’s Day at the Illinois State Fair last month, the usually sympathetic group booed so loudly that not a word of Quinn’s speech could be heard. Quinn wasn’t the only Democrat on the stage booed that day, but he was the main target.

From the union members’ perspective, Quinn’s offenses are many. He has attempted to close union-staffed facilities across the state, ignored union contracts calling for raises, attempted to force union workers to take pay cuts and supported legislation to limit union membership. That seems like a slap in the face for union members, whose campaign contributions and union dues pumped money into Quinn’s 2010 campaign for governor. Now, they say Quinn is acting less like a labor-friendly Democratic governor and more like his Republican opponent, Sen. Bill Brady of Bloomington, who proposed cutting state agencies 10 percent across the board.

But Quinn isn’t the only worry for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) Council 31, the largest union representing state employees in Illinois. AFSCME now faces one of the biggest challenges in its 60-year history: how to address the underfunded state pension systems. The system has an estimated unfunded liability of $83 billion, caused mainly by years of lawmakers diverting money intended for pension payments into other funds. In the resulting political battle, the focus isn’t on holding lawmakers accountable, but on what concessions state employees should make to fix the problem.

Henry Bayer, executive director of AFSCME Council 31, portrays this as a critical time for the union. The political climate has soured toward unions, which Bayer says are portrayed by anti-union interests as “fat cats” living on the public dole, and AFSCME now faces “unprecedented” challenges to both its members and its influence. And because the union represents state workers who perform vital public services ranging from issuing driver’s licenses to investigating child abuse, he reasons that if the union suffers, everyone suffers – from unionized state employees to private-sector non-union workers.

AFSCME itself began in 1932 in Wisconsin, during a period of often violent confrontations between workers and businesses. For the public employees who organized, their concern was less about work conditions or wages and more about losing their jobs because of patronage – the practice of rewarding political supporters with government jobs. The first public union in Illinois was formed in 1942, and numerous state and local government workers began organizing local unions during the 1950s and 1960s.

AFSCME is a branch of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO), the main union organization in the United States, which covers 56 trade unions and about 12 million workers. The Illinois branch of AFSCME, known as Council 31, has about 75,000 members and represents dozens of public employee labor unions across the state, including a handful of unions in Springfield.

A bevy of threats

AFSCME members currently face several threats to their jobs, pay and benefits, and they’ve been handed some resounding defeats lately.

In June, lawmakers passed a law requiring state retirees to pay premiums for health insurance, prompting at least two lawsuits – one from a group of unions including AFSCME and another from retired appellate justice Gordon Maag – which claim

the law diminishes state employee pension benefits in violation of the

Illinois Constitution. The lawsuits await a court ruling.

In

early August, AFSCME began holding emergency meetings to deal with a

negotiation proposal by Quinn to reduce union members’ pay in their next

contract. That controversy hits an especially raw nerve in the midst of

an ongoing court battle over the previous contract. In January 2011,

Quinn and AFSCME struck a deal in which AFSCME members would give up

half the value of their contractually mandated pay raises in exchange

for a promise that Quinn would not lay off 2,600 workers or close any

state facilities until July 2011. AFSCME also accepted voluntary

furlough days and other concessions to save the state about $50 million.

Quinn

later reneged on the deal, saying the Illinois General Assembly hadn’t

appropriated money for even the halved raises. AFSCME filed suit, and

despite a state arbitrator’s ruling that Quinn should pay the increases,

a U.S. district court and a U.S. appellate court both backed Quinn. On

Aug. 30, a Cook County judge ordered Quinn to set aside funds to pay the

raises in case AFSCME prevails on appeal.

The

governor also wants to close seven facilities statewide, including the

Jacksonville Developmental Center and the super-maximum security prison

at Tamms in southern Illinois. AFSCME filed a lawsuit to stop the Tamms

prison closure, saying it would endanger guards and public safety.

AFSCME claims that recent searches of guards at Illinois prisons across

the state were retaliation for guards speaking out about prison

conditions. Speaking to reporters at the Illinois State Fair, Quinn

denied the retaliation claim and declined to discuss the issue further.

There

are even instances of Quinn’s administration allowing state jobs to be

sent outside Illinois. In May, the state awarded a $248,650 contract to

Jacksonville, Fla.-based call center company Veritech Solutions to take

calls for the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional

Regulation’s mortgage fraud hotline. A separate contract for another

state phone bank is currently up for bid.

A brewing battle

AFSCME’s

biggest threat is the ongoing battle over pension funding. The outcome

of this highly controversial issue could set precedent for years to come

and could change how the state’s constitution is interpreted with

regard to state employee benefits.

Each

of the state’s five pension systems have enough money to pay current

retirees for the next several years, according to their annual reports.

In fact, Dave Urbanek, spokesman for the Illinois Teachers’ Retirement

System, says TRS could survive until at least 2030 even if the

legislature cut its annual appropriation for pension payments by $1

billion.

Urbanek says pension underfunding is a longterm problem, not an immediate crisis as it has been portrayed.

While

none of the five state pension systems is in danger of collapse any

time soon, the cost of benefits is expected to grow faster than the

combined value of contributions and the pension systems' income from

investments. Put simply, money is expected to go out faster than it will

come in. That's why lawmakers passed a law in 1995 requiring the state

pension systems to be funded to 90 percent of total liability by 2045.

That law requires a “ballooning” state contribution that gets

progressively larger with time, putting more strain on the budget.

Henry

Bayer, AFSCME’s executive director, says state employees have always

contributed their share to the pension system, but lawmakers have not

followed suit. Urbanek says, for example, between 1970 and 2011, the

legislature redirected $15 billion in funds that should have been

invested in TRS.

But

Paul Kersey, director of labor policy for the conservative think-tank

Illinois Policy Institute, says AFSCME shares some of the blame it

assigns to lawmakers.

“A

union’s responsibility doesn’t end with negotiating a big pension; they

should monitor things to make sure the employer follows through,”

Kersey says. “Less energy should have gone into coaxing politicians into

making new promises, while more should have gone into making sure

they’d keep the ones they’d already made. Some of this is 20-20

hindsight, but at best the union miscalculated badly. At worst, they

were indifferent and reckless with their members’ retirements, or are

reckless with taxpayer money and didn’t think it ever would run out.”

The

variety of proposals to make up the shortfall vary widely in their

impact and potential for controversy. The already-enacted law to make

retirees pay health insurance premiums would save the state about $1

billion per year, but has spawned a lawsuit and could be ruled

unconstitutional because of the Illinois Constitution’s prohibition on

diminishing public employee pension benefits.

Rep.

Elaine Nekritz, a Democrat from Northbrook, introduced a pair of bills

in early August that attempt to comprehensively address the pension

issue. Those bills would make state employees hired before Jan. 1, 2011,

choose between receiving health care benefits as retirees and having

raises count toward their pensions. AFSCME is likely to challenge the

constitutionality of those bills, which would also gradually shift

payment of downstate teacher pension contributions from the state to

school districts. A special session day called in August to deal with

the pension issue produced no action on those bills.

The

Chambers for Pension Reform, a group composed of the Illinois Chamber

of Commerce and several local chambers, has a more Spartan plan. They

say the state should raise the retirement age for state employees,

increase the amount employees contribute toward their pensions and

reduce the level of benefits that have yet to be earned.

The

group’s most controversial idea – shared by the Illinois Policy

Institute – is changing pensions from a system in which benefits are

defined beforehand to a system in which the state makes no promises

about benefits. In the latter scenario, called a “defined contribution” plan,

retirees receive whatever they have saved plus whatever the state has

contributed toward their pension. AFSCME opposes that idea because it

represents the possibility for greatly diminished future benefits.

If

the General Assembly adopts any changes along those lines without first

getting AFSCME on board, the union is likely to challenge the changes

in court. The reason is the Illinois Constitution’s Article XIII,

Section 5, which states that membership in the pension system is a

contractual right, “the benefits of which shall not be diminished or

impaired.” Plans like that of the Chambers for Pension Reform are

careful to address only benefits to be earned in the future, which could

be interpreted as not impairing benefits already owed.

But

AFSCME sees the promise of benefits as a contract itself. When a worker

begins employment with the state, the worker is promised certain

benefits as a term of employment. For AFSCME, reducing that promise of

benefits for people already employed amounts to breaking the contract

protected in the state constitution. Whether or not the benefits have

been earned to date doesn’t matter in AFSCME’s view.

Should

AFSCME lose a court challenge to a plan that amends benefits, it would

likely open avenues for more benefit cuts. While the state probably

won’t switch state employees to defined contribution plans as the

Chambers suggest on this go-round, reform advocates – especially those

hostile to the union – could view a court-approved benefit cut as a

declaration of open season.

Contrarily,

if AFSCME wins such a challenge, it would eliminate talk of reducing

benefits and instead focus attention on ways to reduce state spending or

increase revenues. In the current political climate – already soured by

the 2011 income tax increase that didn’t solve the state’s financial

problems – further revenue increases are likely to be considered toxic

for any politician seeking reelection.

AFSCME

has its own ideas about how the pension issue should be handled. The

organization’s pension reform framework states union members would be

willing to pay “a little more, even though they have contributed their

portion over the years.” That concession would be given in exchange for a

promise that the state would pay its share toward the system. AFSCME

also calls for closing “tax loopholes” like those that excuse from

taxation the offshore profits of oil companies and foreign dividends of

large corporations. The union says those changes could generate nearly

$900 million annually, all of which AFSCME says should go toward the

pension system.

Bayer

says the state should go one step further and enact a graduated income

tax instead of the current flat tax. A graduated tax would create a

higher tax rate for those with larger incomes, which would require a

constitutional amendment. A handful of lawmakers have proposed such

legislation, to no avail.

Budget trumps alliances

How

did this political climate develop, in which a Democratic governor who

has long touted his support for unions now pursues policies that

practically make him the union’s nemesis?

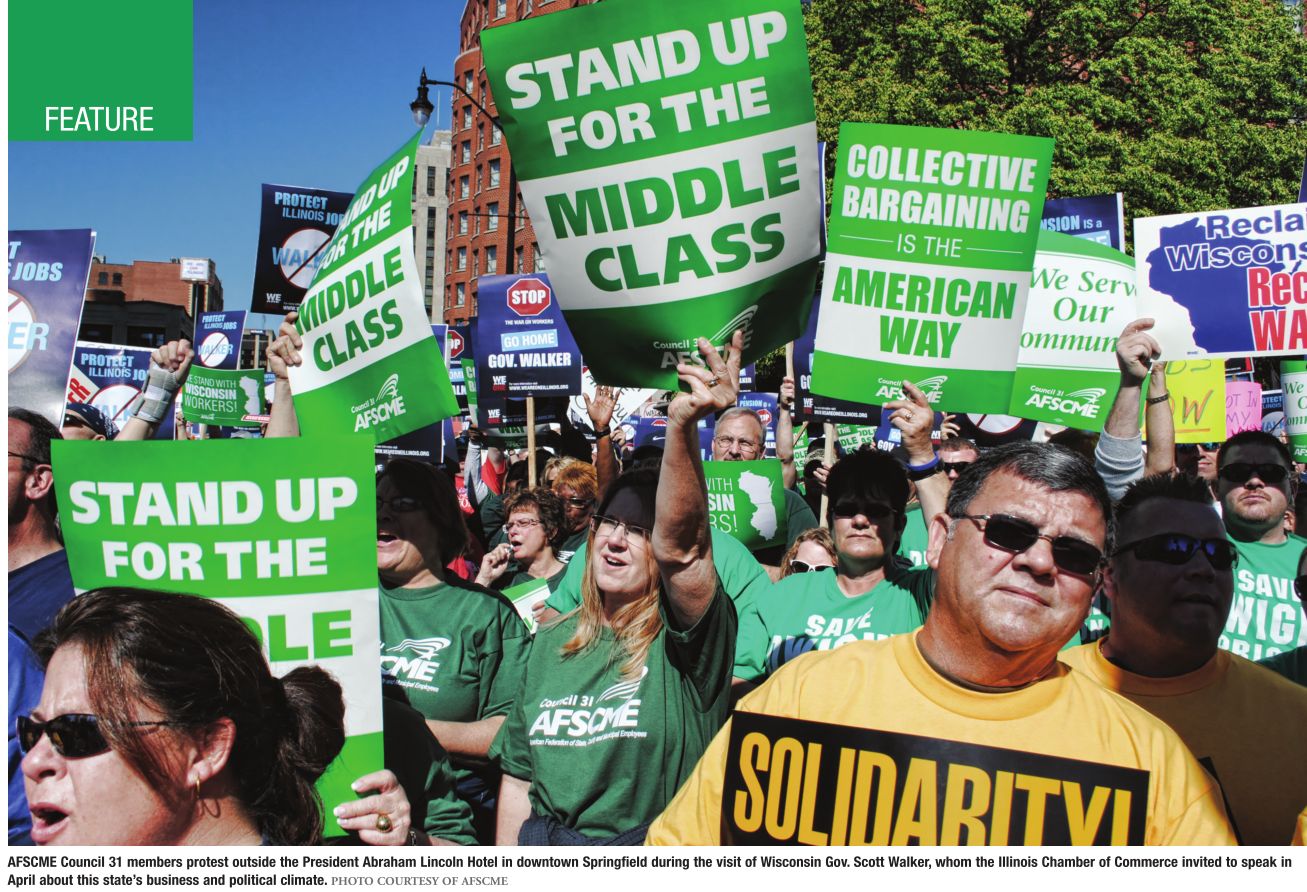

Dr.

Kent Redfield, a longtime observer of Illinois politics and a professor

emeritus of political science at the University of Illinois

Springfield, contrasts Pat Quinn with Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker, who

created a firestorm last year when he attempted to rescind many

collective bargaining rights for

state

workers in Wisconsin. Quinn and Walker share a desire to improve their

respective states’ financial standings, Redfield notes, but their

ideology differs. He describes Walker’s views as “free-enterprise,

government is the enemy,” while likening Quinn to the good-government

political reformers of the 1960s and 1970s.

“Quinn’s

trying to balance the budget,” Redfield says. “He’s ambitious. I take

him at his word in the sense that he wants to solve the state’s

problems. It really all goes back to the budget. The hole was so deep

that even with the temporary tax increase, you couldn’t get your way out

of it.”

That massive

budget hole – as much as $8 billion by some estimates – caused Quinn to

shift from idealistic to pragmatic, Redfield explains.

“The

things that you can control with the state budget are public employee

wages, hiring, pensions, that kind of thing,” he says. “There aren’t a

lot of options on the expenditure side that don’t involve employees.

Even if you fired every state worker, you wouldn’t have enough money to

get that hole filled, so it isn’t the public employees who cause the

problems, but there aren’t a lot of other options for cuts.”

Henry

Bayer, the AFSCME executive director, says another force is at work. He

notes that former Gov. Jim Thompson – a Republican – signed the law

that gave public employee unions statewide the power of collective

bargaining.

“It’s hard

to fathom a Republican governor signing a collective bargaining bill

now, because politics have moved so far to the right,” Bayer says. “The

political climate has changed dramatically, and the financial and

business community has more say in shaping public policy. It’s a much

more conservative climate that is hostile to working people.”

But while Bayer classifies the pension reform battle as “an assault on the middle class,” the Illinois Policy Institute sees the situation as the natural outcome of years of mismanagement.

“What’s

assaulting them is reality,” says Paul Kersey, director of labor policy

for IPI. “Illinois’ pension system is unsustainable. Without reforms,

there is a distinct possibility that the systems will eventually

collapse, leaving retirees with close to nothing. Organizations pushing

reform such as the Illinois Policy Institute could well prove to be

state employees’ best friends.”

Kersey sees AFSCME and other unions as roadblocks rather than victims.

“AFSCME

is increasingly becoming a negative force in Illinois, not just for

taxpayers but for their own members,” he says. “First, the political

machine AFSCME and other government unions have built is an obstacle to

creating the leaner government Illinois needs. But perhaps worse,

without reform it is AFSCME’s own members who will be hurt. If the

pensions are not reformed, we will get to a point when the funds run dry

and it’s state workers who don’t get their retirement money.”

Meanwhile,

Redfield says AFSCME’s voice on the pension issue is less influential

because of the perception that there aren’t many options for reform

except cuts to state employee pay, pensions and benefits.

“People

who are their traditional friends are really under a lot of cross

pressure,” he says, adding that the political debate sometimes misses

the mark. “Talking about ‘greedy public employee unions’ sounds good at

one point, until you need a policeman or a fireman, or you want good

teachers so your kids can get an education. There’s no Bureau of Waste

and Fraud. The abstract is very different from the reality. The state

provides essential services.”

Those

services could suffer if Illinois doesn’t get back on track soon

because the state “is getting a reputation as a very undependable

employer,” Redfield says.

“You

want the best and the brightest to come work for your universities,

your schools, your regulators, your prisons, and all of that,” he

explains. “If you don’t get good, confident people, then you’re going to

get even less in the way of services because they’ll be inefficient and

ineffective.”

The current election cycle could mean even more trouble for AFSCME because of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizens United ruling,

which rejected limits on independent expenditures favoring a particular

political candidate. Because Republicans tend to have more money to

spend on election advertising, Redfield expects Democratic election

messages to be overshadowed and diluted.

Bayer says he has seen the effects of the decision already in congressional campaigns.

“There’s

no way the labor movement can raise anywhere near the amount of money

they have,” he says, referring to business interests.

Meanwhile, both Bayer at AFSCME and Paul Kersey at IPI recognize the importance of this moment in political history.

Kersey sees the circumstances as an awakening of people concerned with government waste.

“The

Wisconsin reforms, the passage of right-to-work in Indiana, and

Michigan’s labor reforms over the past few years have woken up people in

the Midwest,” he says. “Government unions having a monopoly over public

services is becoming an antiquated way of living, and that’s why

Illinoisans are pushing back.”

Bayer, on the other hand, sees it as part of a nationwide battle between business interests and workers.

“There

are strong forces out to destroy the unions,” he says. “They want to

weaken the labor movement so they can have their way politically. We’re

prepared to do battle. We think this assault on the middle class, if

successful, is going to change this country.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].