Goodwill Power

Central Illinois charity roars back

BUSINESS | Bruce Rushton

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AUG. 9, 2020 Land of Lincoln Goodwill Industries today announced the acquisition of all Walgreen stores in central Illinois.

“It’s a good fit for our mission,” said Sharon Durbin, president and chief executive officer of the Springfield-based charity, which already had more than 100 retail stores. “We’ll be able to employ more people than ever, plus reduce the cost of prescription drugs for our existing employees. It really is a win-win.”

Coupled with last year’s buyout of Family Video, Land of Lincoln Goodwill now controls more commercial real estate in Illinois than any company in the state. The charity is rumored to be in negotiations with Wal-Mart, which has seen sales plummet as Goodwill refuses to be undersold on everything from used toasters to its own line of designer jeans manufactured in the basement of the former Crowne Plaza Hotel, which was donated outright in exchange for a tax deduction.

“This is just the beginning,” predicted Durbin as she eyed the capital city from her penthouse office in the former hotel, now dubbed Goodwill at the Trump to honor the New York billionaire who paid for renovations so his name would be inextricably tied to the juggernaut that is Goodwill.

Land of Lincoln Goodwill Industries hasn’t taken over the world – yet. It just seems like it.

Revenue is skyrocketing. Stores are opening. Employment is exploding. Television commercials are airing. Sharon Durbin, who had never run a business or a charity before she was hired as Goodwill’s CEO and president in 2006, is smiling at a transformation that has made Goodwill much more than a place that runs thrift stores and employs the developmentally disabled.

“We’re moving upward, and that’s what counts,” Durbin says.

Goodwill was staggering when she took over. Larry Hupp, the former executive director, was forced to resign in 2005 by the U.S. attorney’s office, which threatened to prosecute him for Medicaid fraud if he didn’t quit.

Federal investigators who served a search warrant at the charity’s sheltered workshop found the agency, which was running a deficit, falsified records to get $38,000 in public money that it didn’t deserve. Stores tended toward small and dingy.

“When I started at Goodwill, I didn’t know what the mission was,” said Debbie Rzodkiewicz, who started out as manager of the charity’s store on Dirksen Parkway eight years ago and is one of the few employees who has worked at Goodwill for more than five years. “I was the only permanent employee. I had no idea where the money went or what Goodwill actually did.”

Rzodkiewicz, who is now a production manager who oversees the path that goods take to sales floors, believes that most people still don’t know why the charity exists.

“They just think that we sell cheap clothes,” she says.

The mission

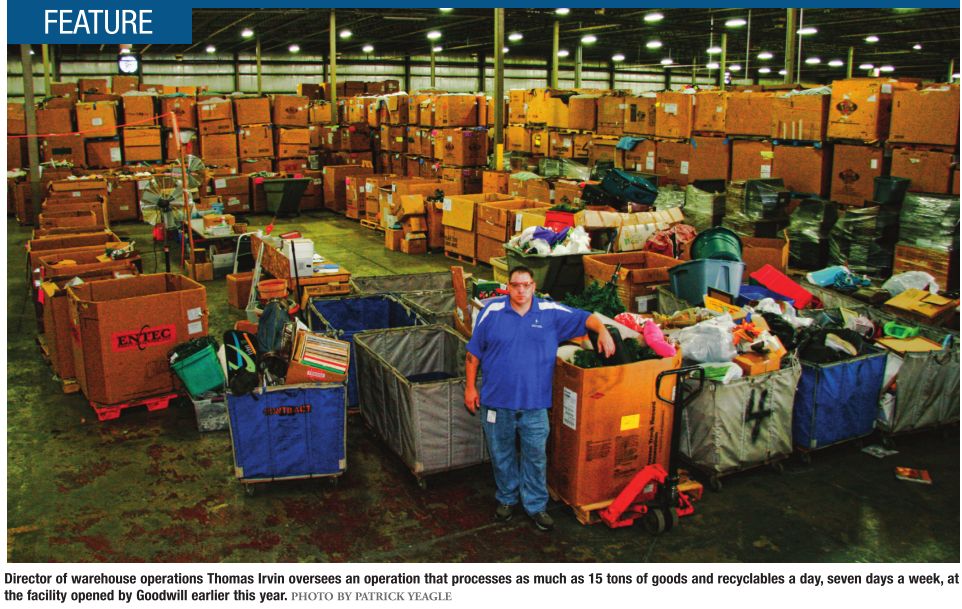

It’s not yet 10 a.m., and Goodwill’s warehouse on Lumber Lane in east Springfield is sweltering. But the folks who run this 80,000square-foot behemoth of a building say they’re not cruel.

“We’ll shut down the operation if it gets too hot,” says Thomas Irvin, director of warehouse operations.

How many times has the warehouse closed since Goodwill opened it six months ago, after a St. Louis-based tire company departed the space? Well, never. How high has the temperature in the warehouse reached? Ninetyeight degrees. Coolers containing cold water are within easy reach of employees who empty one truck after another filled with donated goods.

“This is a seven-day-a-week operation,” Irvin says.

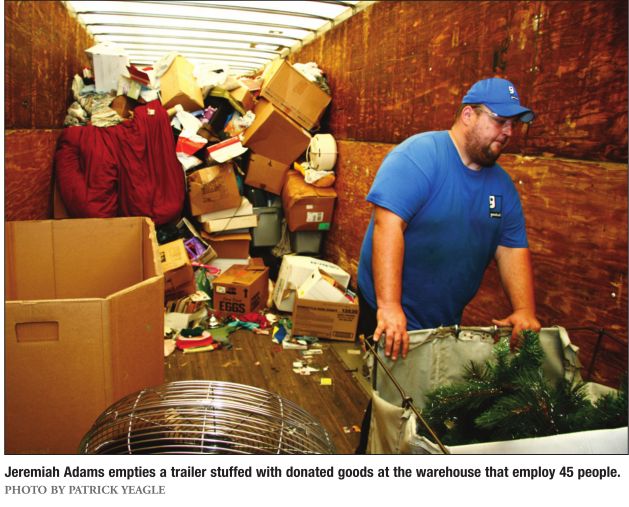

There is plenty of work for the 45 warehouse employees who each day sort through as much as 15 tons of shirts, hats, jackets, VCRs, keyboards, televisions, record albums, cardboard, garden tools and just about anything else you can imagine. This is where things from donation centers are brought before being sent to stores, presuming the goods are saleable, and things that can’t be sold are organized for recycling.

Clothing that is stained, torn or hasn’t sold after five weeks in stores is baled up and sold by the pound to buyers who will ship the cream to developing nations with high poverty rates and turn the rest into rags. Shoes are also recycled, perhaps to become the surface for a playground basketball court or artificial turf in a professional football stadium.

Little is wasted. Goodwill expects to pay $200,000 in landfill costs this year, and sending anything to the dump clearly hurts.

“That shouldn’t be there,” says Chris Lee, director of salvage and recycling, as he eyes a pre-Eisenhower 78-rpm record album atop a pile of cellophane and paper scraps in a trash bin. There are also plenty of homemade VHS tapes, which, unlike commercially produced ones that are sold in the charity’s stores, have proven a challenge.

“I’ve been looking for years to find a vendor for them,” “I’ve been working for years to find a vendor for them,” Lee says. “I can’t find anyone.”

During July, Goodwill’s trucks traveled nearly 18,000 miles, and that’s a typical month. Between 75 and 80 trucks are loaded and unloaded at the warehouse during any given week. Not just anyone can work here.

When it’s cold outside, it’s cold in here.

There isn’t any sitting down, nor is there much chance to slack off. Supervisors know how long it should take to process goods, and they keep track of how much time it takes to empty trucks and fill boxes. Free steel-toed boots, brand new from Red Wing, are a fringe benefit, but the pay is low, less than $10 an hour. And Goodwill is not keen on commuting to work.

“The employees are all from this area,” Irvin says. “We try to hire from the community.”

Who would take such a job? Someone like Irvin, who started out as a material handler, emptying bins for $8.25 an hour, when he moved back to Springfield from Colorado, where he worked on a farm. In the space of five years, he has gone from sorting donations to manager. He wants to further his education, and he isn’t worried about juggling work and classes. Goodwill, which encourages employees to find better work elsewhere, has helped him find financial aid. So long as he shows up when he’s supposed to and works hard, he’ll have a paycheck while attending college.

“That’s all we do is work around people’s lives,” Irvin said.

Employment figures are dizzying for an agency that had just 25 workers five years ago. In mid-June, Goodwill had 351 employees. Last week, the number stood at 429, and the help-wanted sign is still out.

“The more you do, the more people you have to hire,” Durbin says.

The agency, which runs 10 stores in Springfield, Bloomington, Lincoln, Chatham, Effingham, Danville, Champaign and Jacksonville, is planning a new store in Litchfield, and Taylorville looks promising. In Chatham, work has begun on a high-end boutique shop that will be attached to the existing Goodwill store, and another boutique is planned for the Champaign store. A bookstore with a music stage, café and drivethrough – Barnes and Noble is the template – is on the drawing board for the Wabash Avenue store.

Goodwill hires most anyone who is willing to work. Recovering alcoholics and drug addicts? Sure, if they can pass a drug test. Felons? They’re also welcome, so long as they’re not sex offenders. High school dropouts? Why not? New employers who last three months get full benefits, including health insurance and paid vacation.

Goodwill is a veritable land of second chances, according to Irvin and other managers. If an employee isn’t cut out for the warehouse, they can try working in a store. Stealing is one of the few transgressions that results in instant termination; there is a lossprevention program complete with cameras to ensure honesty.

Goodwill is a veritable land of second chances, according to Irvin and other managers. If an employee isn’t cut out for the warehouse, they can try working in a store. Stealing is one of the few transgressions that results in instant termination; there is a lossprevention program complete with cameras to ensure honesty.

In many cases, the biggest challenge is getting people who have never held a job to believe in themselves, Durbin said. It is not all butterflies, puppy dogs and rainbows as the charity strives to break cycles of welfare and teach people to fish instead of providing handouts. While Goodwill stands ready to help, some people simply are not willing to work or show up on time or show up at all.

Consider programs to help people pay medical or utility bills. Goodwill will pay up to $200 in bills if debtors work 25 hours for the agency. Goodwill will pay $720 in bills for folks who commit to a 140-hour, monthlong program that is half work, half education, aimed at teaching job skills. It is an allor-nothing proposition – the agency doesn’t pay a dime if enrollees don’t complete the program. Graduates include an 86-year-old man who got behind on his utility bills and ended up with a GED.

It’s a perfect audition for full-time employment, and enrollees who show promise have gotten job offers from Goodwill.

But one third drop out, even though they may arrange for friends or relatives to help complete the work requirement.

“There are people who walk through our doors, no matter how much you want to help them, you can never help them because they’re always wanting to manipulate the system,” Durbin says.

If Durbin and her top managers have a favorite word, it is “mission.” Goodwill’s mission, they say, is helping people help themselves by putting them to work or teaching job skills or helping with job searches.

We empower people with special needs to become self-sufficient through the power of work.

That’s what it says on the agency’s website and the wall of the reception area at Goodwill’s headquarters on Outer Park Drive in a building that was once home to Cherry Hills Baptist Church. “Special needs” can mean a lot of things: Single moms who’ve been victims of domestic violence, people with mental illness or dyslexia or learning disabilities. It can even mean someone without a computer at home. The agency’s headquarters includes a computer lab where job seekers can work on resumes or learn to use such programs as PowerPoint or Excel.

In the past, Goodwill focused on helping the developmentally disabled, and to be sure that is still the case. A way-past-its-prime former shoe factory on North 10th Street that was agency headquarters during the dark days is still home to a store and a sheltered workshop where 72 disabled people come to earn a little cash by sorting jewelry for stores, assembling fishing lures and doing sundry other tasks that would bore many folks to tears. The surrounding neighborhood is crumbling, and the building sits spitting distance from Norfolk Southern railroad tracks.

“I hate them being out there,” Durbin says.

The agency, which provides transportation to and from the 10th Street workshop, recently replaced 15-passenger vans with airport-style shuttle vans better able to accommodate wheelchairs. While Durbin wants a new work space, acquiring a building that can accommodate the needs of disabled workers, including all aspects of the Americans With Disabilities Act, is neither easy nor inexpensive. She is hoping that the 10th Street building, which has been on the market for several years, will be purchased by the government as part of a rail consolidation plan aimed at moving downtown railroad tracks to the Norfolk Southern corridor.

During the fiscal year that ended June 30, 2011, Goodwill, which had revenue of more than $16 million, took in $390,000 in government grants, according to the agency’s most recent financial statements submitted to the Internal Revenue Service. While she’s grateful for public money, Durbin dreams of a day when Goodwill is self sufficient. The problem with government money, Durbin says, is the strings.

For example, a U.S. Department of Justice grant that funds a youth mentoring program aimed at putting more than 100 atrisk kids in college instead of jail doesn’t allow spending for food, which is deemed entertainment. The government pays salaries for program administrators and travel expenses so kids can tour college campuses, but when they stop for lunch, money for hamburgers or pizza has to come from other sources.

“It’s just not realistic – you get a bunch of teenagers together, they have to eat,” Durbin says.

It is not, quite literally, a free lunch. The charity recently received a donation of basketball shoes for the youth program’s traveling hoops team, but team members, who travel as far as Kentucky to play, had to wash the charity’s trucks and detail the interiors before receiving their shoes.

The business

When Durbin arrived, Goodwill was operating on annual revenue of about $6 million.

She has a target of $34 million and points to Goodwill Industries of the Columbia Willamette, based in Portland, Ore., as evidence that it can be done.

Durbin may actually be selling herself short, according to Michael Miller, CEO and executive director of the Portland Goodwill, which topped $122 million in revenue last year and is considered a national model.

“In 2011, we achieved market penetration equal to $37 per capita in our assigned territory,” says Miller as he crunches numbers aloud with the ease of someone who has been running Goodwill chapters since 1976. “If she (Durbin) can achieve $30 in percapita sales, she would be at $40 million in retail program revenue. Even if she only gets to $20, that would put her at $27 million.”

Durbin, who was an Illinois Department of Transportation bureaucrat with the title of metropolitan planning manager, had never hired anyone before she got the top post at Land of Lincoln Goodwill Industries, which serves 37 counties stretching from Quincy to the Indiana border. She wins high marks from Miller.

“I would describe the turnaround she’s achieved as amazing,” Miller said. “She is well underway.”

There is an element of serendipity. Thrift stores nationwide have benefited from a tight economy that mandates frugality, Miller said, and an emphasis on reducing waste has also helped.

There is an element of serendipity. Thrift stores nationwide have benefited from a tight economy that mandates frugality, Miller said, and an emphasis on reducing waste has also helped.

“There’s a very large segment – about 30 percent of the people in the United States are thrift shoppers,” Miller says. “Some of the stigma that might have been associated with thrift shopping 30 years ago has faded over time.”

A modern Goodwill is, most decidedly, not your grandfather’s Goodwill. At the Wabash Avenue store, Edgar’s Coffee House offers gourmet roasts, sandwiches, muffins baked on premises and a catering service – it’s become a gathering spot for groups ranging from red hat ladies to Drinking Coffee Liberally, an offshoot of the left-leaning discussion group Drinking Liberally. The basement is a beehive where brand-new goods purchased at steep discounts are stored in preparation for sale and a used-book operation sells 2,000 volumes a month on Amazon. Large bins filled with used pink fiberglass insulation sit next to the book operation – eventually, Durbin figures, they will come in handy for something.

Also in the basement is the charity’s online sales division where high-end wares are put up for auction on shopgoodwill.com, a website mimicking eBay where goods from Goodwills across the nation are put up for sale. If you donate a mink coat, a Pendleton blanket or a rare comic book to Goodwill, there’s a good chance it will end up here. A donated Rolex watch sold for more than $3,000.

“I was very, very happy with how it ended,” says John Lancaster, e-commerce manager, who checks out such treasures to ensure authenticity and has no idea who donates such items. “The man who bought it emailed us when he received it and was excited about receiving it and couldn’t wait to show all his friends.”

Rolexes. Amazon. Gourmet coffee.

What’s next? Well, a mortgage. After two years of purchasing its Outer Park headquarters on a contract-for-deed basis, Goodwill recently signed a loan agreement with Carrolton Bank and expects to have the debt paid in four years. The interest rate, Durbin says, was too good to pass up, and she didn’t go shopping for a loan.

“They called us,” Durbin says. State Fourth District appellate Judge Thomas Appleton, who has been on the charity’s board for 31 years, credits Durbin for the agency’s resurgence. Betting on her passion, the board chose her over candidates with more experience, including applicants with years of experience running Goodwills in other states, he said.

“Sharon came in and, frankly, was more impressive than any of the other people who had been with Goodwills before,” Appleton said. “I guess it’s an American success story, isn’t it?”

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].