State agencies scramble to avert crises as funding vanishes

12 GOVERNMENT | Patrick Yeagle

Marc Miller has been an outdoorsman for as long as he can remember.

Miller says he grew up in a family of hunters, anglers and camping enthusiasts, but also learned the value of protecting the land. He’s a combination of conservationist and environmental advocate, which is fitting for his position as director of the Illinois Department of Natural Resources. But Miller’s breadth of interest and experience also makes DNR’s current financial situation doubly painful for him.

DNR has long dipped into special funds to supplement its budget and pay for operating expenses as allowed by law, Miller says, but the practice has intensified greatly in recent years because the department’s annual budget has been cut by $58 million over the past decade, a 55 percent reduction.

Miller likens it to burning the furniture to heat the house.

Now, those special funds upon which DNR has relied are becoming depleted, leaving Miller’s department without enough staff, adequate equipment or money for even basic maintenance. DNR lost 43 employees from 2011 to 2012, and the department is expected to lose another 34 employees in 2013, leaving the total headcount at 1,150 statewide. In the past two fiscal years, DNR’s budget from the state’s General Revenue Fund has decreased from about $61 million in FY11to $50 million in FY12. For FY13, which starts on July 1, that number is expected to drop to about $45 million.

“It’s very difficult to do all the work mandated for our agency,” Miller says. “We can’t go any lower. We need to be thinking about what kind of work we need to be doing to fulfill our core mission.”

DNR does more than just mowing state parks and selling fishing licenses. The depart ment oversees oil and coal permits, inspects coal mines to ensure their safety, manages stormwater and flood control efforts, holds boating, snowmobile and hunting safety courses, protects endangered animals, and a variety of other tasks mandated by state law.

Already, DNR has started dialing back services and reorganizing priorities. In March, DNR issued its last edition of Outdoor Illinois, the monthly nature magazine the department has published since the 1970s, when it was an informal newsletter. Cutting the magazine wasn’t easy, Miller says, but it had to be done for the good of the department. In the final edition, Miller wrote an article describing DNR’s woes and issuing a grim forecast for DNR’s future.

“Unless there is relief or a change in the agency’s business model, the deferred maintenance at parks will continue, staff will not be replaced when they retire or otherwise leave the agency, and there will be limited or no replacement of old vehicles and equipment,” Miller wrote. “Important programs that protect resources and natural areas will diminish, and wildlife, fisheries, forestry and law enforcement programs will decline. Our ability to monitor and regulate floodplains and industry, as well as protect public health and safety, will be reduced.”

DNR is one of several state agencies in Illinois already suffering from past budget cuts – a condition likely to worsen as the state further reduces spending for the next fiscal year. While Gov. Pat Quinn and state lawmakers say reductions are necessary to bring spending in line with current revenues, the consequences are likely to be cuts or delays in public services, along with increased longterm costs due to deferred maintenance and inefficiencies created by staff shortages.

That’s on top of the social toll of cutting programs that provide care

and support for the elderly, the mentally ill, the disabled and the

poor. The price they’ll likely pay can scarcely be measured in dollars.

Smaller staffs, fewer dollars

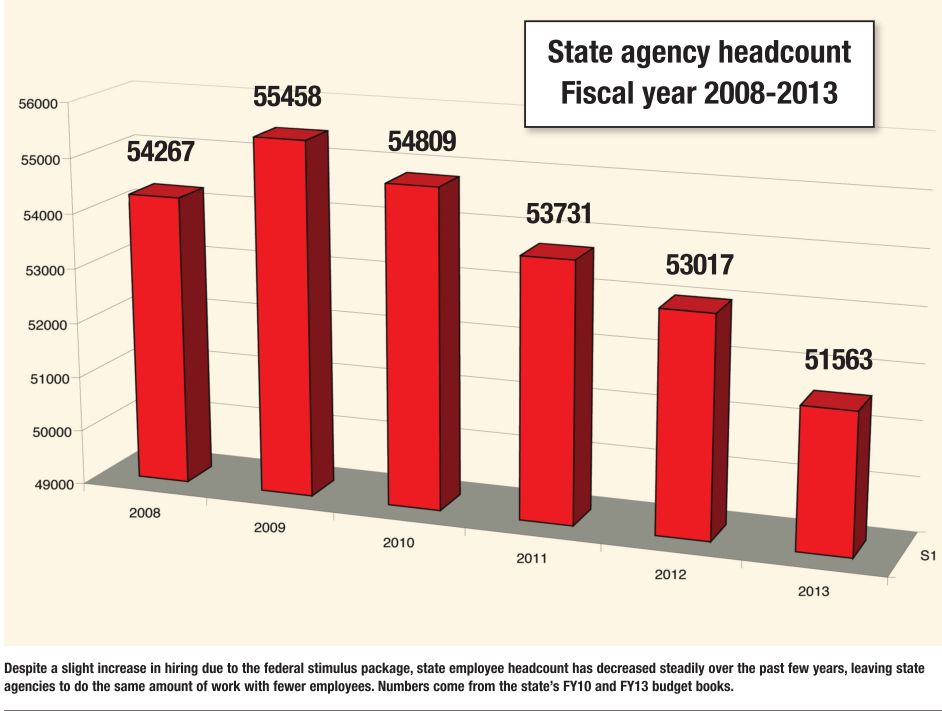

For

many state agencies, a reduction in funding can translate into fewer

workers, which means larger workloads for the remaining staff. State

employee headcount in Illinois has dropped over the past five fiscal

years, following a large decrease from the 1990s. Numbers from Quinn’s

office show the total statewide headcount at 54,267 in 2008. That number

increased slightly because of extra staff hired to implement programs

under the federal American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, but the

headcount has since continued to decline. Currently, Quinn’s office

estimates the state has 51,563 employees, which represents a decline of

2,000 employees since the start of 2009. Illinois now has the lowest

state employee headcount per capita of any state, Quinn’s office claims.

Recent

audits from the office of Illinois Auditor General Bill Holland provide

several examples of understaffed agencies struggling to do all of the

work mandated by law.

Recent

audits from the office of Illinois Auditor General Bill Holland provide

several examples of understaffed agencies struggling to do all of the

work mandated by law.

•

The Illinois Department of Revenue blames understaffing for a backlog

of unprocessed tax returns. The department has lost 194 people since

June 2011 and has only hired 53 workers to replace them – an eight

percent total reduction in headcount.

•

The Illinois State Fair lacks enough staff to ensure all vendor

contracts are signed before the contract period starts, exposing the

state to “unnecessary legal risks” and expenses.

•

The Illinois Department of Public Health partly blamed staff shortages

for its inability to adequately monitor whether grant recipients used

state funds appropriately.

•

The Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services said it

doesn’t have staff available to create a procedures manual explaining

how to set premium rates for the Teacher’s Retirement Insurance Program

(TRIP). That knowledge rests with only one person in the department, the

audit notes.

Those

who work in agencies that are struggling to completely fulfill their

mission describe low morale and apprehension among employees.

Terry

Meacham is a mental health technician at the state-run H. Douglas

Singer Mental Health Center in Rockford and secretary of his local

branch of the American Federation of State County and Municipal

Employees (AFSCME), the largest union representing state employees.

Meacham says Singer, which is overseen by the Department of Human

Services, is understaffed by 10 to 12 people, and patients sometimes

wait several days for treatment, with some even spending nights in the

waiting room. The facility has been targeted for closure, though the

legislature has appropriated money to keep it open for the coming fiscal

year.

“People are

terrified,” Meacham says regarding the uncertainty. “Some of them have

dedicated 20 or 30 years. This is their life. Most of us really enjoy

the work we do.”

Singer

provides mental health treatment for people in 23 counties, says

Meacham. If the facility is closed in the name of saving the state

money, Meacham predicts larger social costs in the long run.

“The

people we serve are going to suffer greatly,” he says. “Jobs will be

lost. There will be an economic loss. Crime rates will go up. Suicides will go up. It’s a hard battle.”

Bruce

Dubre has worked for the Department of Children and Family Services in

Springfield for 22 years, much of that on the child abuse hotline,

though he now works in the agency’s policy department. He’s also chief

union steward for his local branch of AFSCME. He says his coworkers at

DCFS “are in absolute panic.”

“People

don’t understand how we got to this point, and they’re terrified of

what’s going to happen,” Dubre says, adding that his department could

lose as many as 375 workers. The state budget passed by lawmakers in May

contains about $1.17 billion for DCFS, a reduction of about $83 million

from the previous fiscal year.

A

reduction in headcount for DCFS would jeopardize the department’s

ability to comply with a federal consent decree requiring caseloads to

remain below a certain threshold, says DCFS spokesman Kendall Marlowe.

He

says the department will likely have to cut the Intact Family Services

program, which seeks to avoid removing children from their homes by

providing families with education, services and support to eliminate the

root

causes of abuse and neglect. That’s one of the only areas DCFS can cut

without neglecting legally mandated duties, but even that cut won’t be

enough, Marlowe says. DCFS has about 250 workers in the Intact Family

Services program, so the agency will have to cut even more workers from

other programs to stay within budget, Marlowe says.

He and Dubre lament the cuts as negatively affecting the children DCFS serves.

“There

are going to be kids out there who get hurt because of these cuts,”

Dubre says. “It’s not unlikely for some child to die because they’re not

going to get the services they need, and without services, there’s a

strong possibility the family is going to continue to neglect or abuse

the child. Some kid is going to get hurt or killed, and that’s what it’s

all about: protecting children.”

Decades in the making

Illinois is currently – some would say finally

–

attempting to address underfunding of its long-term state employee

pension liability, but that reckoning is now putting stress on the rest

of the state’s budget. While the State Employees Retirement System has

enough cash to pay current retirees, state law requires that pensions be

funded enough to cover 90 percent of all existing and future pension

liability by 2045. That means by 2045, the state must have enough money

to pay 90 percent of all employees if they all retired at

once. Currently, the pension system is funded at about 45 percent, which is about $83 billion shy of the target.

After

several years of skipping payments to the pension system, the state

must now pay ever-increasing amounts to catch up, explains Kelly Kraft,

Quinn’s spokeswoman.

“What

happened here is past lawmakers backloaded the payment schedule so the

large payments would come due now, and as the years go on, the payments

keep increasing,” Kraft says. “Increased benefits were also promised

without the revenues to back up these promises, and pension holidays

were also taken. That is why we need to enact additional pension reforms

immediately.”

For

Fiscal Year 2013, which starts on July 1, Illinois must put more than $5

billion of its $30 billion general revenue budget toward pensions. The

state’s full FY13 budget is about $61 billion, but most of that money

comes from funds already earmarked for other purposes. Kraft says the

current $5 billion pension payment is three times what the state had to

pay in 2008, illustrating the rapidly rising cost of adequately funding

the pension system.

Quinn

and legislative leaders are currently negotiating pension reforms,

though any changes could come under judicial scrutiny because of the

state constitution’s prohibition against reducing state employee pension

benefits.

The Center for Tax and Budget Accountability (CTBA), a nonpartisan group offering budget and policy

analysis, says Illinois’ problems will continue to worsen because of a

“structural deficit” built into the state’s tax system. The growth in

tax revenue has not kept pace with the increasing costs of providing

public services at the same time that demand for those services is

growing due to stagnant private sector wages, a faltering job market and

other social problems.

Human

services like health care, nursing care and child protection services

alone cost Illinois almost $13 billion in the current fiscal year.

Education costs the state about $9 billion a year. Those two areas of

service together consume nearly 84 percent of the $26.9 billion that the

state spent from its General Revenue Fund for the current fiscal year,

which ends June 30.

Even

the temporary income tax increase enacted in 2011 wasn’t enough to

offset the rising cost of providing public services, CTBA says. The

group says the solution is to enact a graduated income tax to replace

the flat income tax specified in the state’s constitution. A proposal to

create a graduated tax met with little support in the most recent

legislative session, failing to even be called for a committee hearing.

Quinn

spokeswoman Kelly Kraft is careful to avoid the thorny subject of what

will happen when the temporary tax increase expires in 2014, though she

says it has helped address the state’s backlog of bills by reducing the

delayed payment cycle by about two months. Lawmakers could decide to

extend or make permanent the tax increase, but it’s likely to be an

extremely contentious issue because 2014 is the next election year for

the office of governor and several legislative seats.

“The

temporary tax increase was needed to address the decades of poor

financial decisions decades of fiscal mismanagement in our state.”

Triage

For

now, Marc Miller has hope for the future of the Department of Natural

Resources, despite the tough financial situation. Like many other state

agencies, Miller’s department is working through a difficult process of

that have been made in the state of Illinois,” Kraft says. “These bad

financial decisions created the structural deficit in Illinois – the

hangover, if you will – and these past bad decisions have come home to

roost. … Most areas of state government have been working at lean levels

for quite some time due to spending cuts and reorganization, while also

searching for new sources of revenue. For these agencies, constant cuts

and uncertainty are likely to be the new normal.

“The people we serve are going to suffer greatly. Jobs will be lost.

There will be an economic loss.

Crime rates will go up. Suicides will go up. It’s a hard battle.“

In

the meantime, DNR awaits legislative approval for fees on activities

like horseback riding and all-terrain vehicle riding in state parks,

which Miller said have already been agreed upon by groups representing

those interests. Hunting and fishing fees will not increase, Miller

says, because hunters and anglers have already paid fees for years.

Additionally,

Miller says his staff reviewed more than 800 mandated duties assigned

to DNR to determine priorities and even have some of them removed from

his department through legislation. Reducing DNR’s mandates is expected

to save the department $1 million annually, while the process of

reviewing the department’s duties revealed about $10.7 million in

additional savings through more efficient management. DNR spokesman

Chris McCloud says that extra effort showed the agency is “not just

advocating for more dollars without trimming inefficiencies.”

Miller

says he hopes the public lobbies lawmakers on behalf of DNR, especially

after he says the department made strides toward more responsible

management.

“The

people who work here on front lines care deeply about the mission and

trying to succeed,” Miller says. “If you’re somebody who works in the

natural world, you can see the resilience of nature and take heart in

that and know that you can see things turn around. We’re not going to

dwell on the past. We’re going to go to work every day, trying to make a

difference and make things better.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].