FOOD | Julianne Glatz

Many years ago, I bought sea scallops. It was a cool day. I came home directly from the store and refrigerated them, but when I opened the bag to start cooking, a nauseating smell hit my nostrils. Even now, remembering that smell makes my stomach turn. I resealed the bag and stuck it back in the fridge. We had something else for supper.

The scallops weren’t cheap, and the next day I returned to the store, nicely explained the situation to the woman who’d sold them, handed her the bag, and asked for my money back. She opened it and immediately the disgusting aroma (now even worse) filled the air.

“They seem OK to me,” she said. “They’re really not,” I replied firmly (but still nicely), trying not to gag. She looked at me with a scowl. “Well, I’ll give you your money back,” she said grudgingly, “but scallops are supposed to smell strong.”

No, they’re not. Scallops should have barely any odor at all; what odor there is should be clean and fresh, like an ocean breeze. Since then I’ve always asked to smell fish or seafood before buying it. It’s totally appropriate to do; no reputable fishmonger will be offended. And I’ve since learned that scallops are either dry- or wet-packed. Now I also always ask if scallops are dry-pack, whether in a restaurant or buying scallops to prepare myself. And if the server (at least after checking with the chef) or fishmonger doesn’t know, I’ll pass.

Scallops are more perishable than many other seafoods, consequently, they’re typically shucked on the boat as they’re caught. Most are then wet-pack: soaked in a solution of water and sodium tripolyphosphate, or STP. The chemical, which acts as a preservative, is generally recognized as safe when used in moderation. STP also plumps scallops up with water — and that’s the problem. Strong solutions cause them to increase in weight by as much as 25 percent, which sellers use to

increase their “production.” But it also gives the scallops an unpleasantly tinny taste, and the unnatural amount of absorbed moisture that exudes when they’re cooked makes it impossible to brown them properly. Even if they won’t be browned, that chemical-tasting liquid flows into the dish. Yuck!

Dry-pack scallops are packed in ice and shipped immediately. Even without asking, it’s usually easy to tell whether scallops are wet- or dry-pack. Dry-pack scallops are ivory, palest tan, or even pinkish, with slight color variations between the individual scallops. Wet-packs are a uniformly bleached white and usually sitting in a pool of milky liquid. You’d expect dry-packs to be costlier, but that’s not always the case. Very cheap scallops (frozen or fresh) are sure to be wet-packs, but I’ve seen wet-packs offered at prices I’ve paid for higher quality dry-packs elsewhere. Locally, Robert’s Seafood usually has dry-pack scallops for sale.

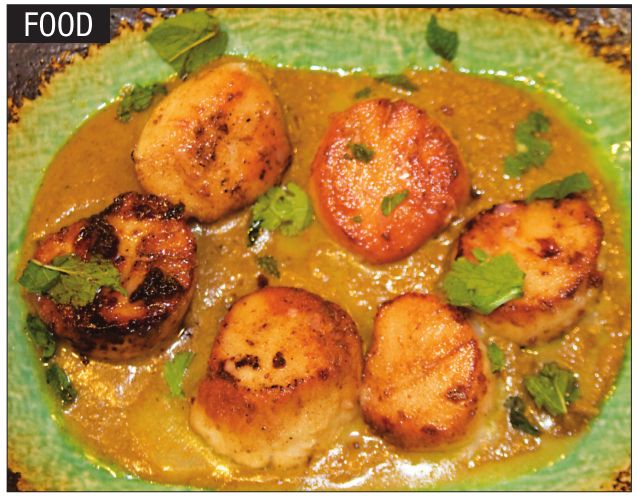

Basic instructions for cooking scallops

Cooking scallops is easy and fast – in fact, the only potential concern is making sure they’re not overcooked, in which case you’ll be eating tasty morsels with the texture of a rubber band. Scallops available locally are usually either small bay scallops – about an inch long and as big around as a thumb, or larger sea scallops (although bay scallops are also technically sea scallops, because they live in salt water) that vary in size from a half dollar to behemoths nearly three inches across. Most scallops needn’t be salted – their innate saltiness from the sea is enough.

To cook bay scallops: Pat them dry (even if they’re dry-pack scallops, they’ll be damp) with paper towels or a lint-free cloth. I lightly oil either a wok or large skillet, over high heat, and stir-fry them. Don’t

overcrowd the pan – it’s better to do them in two batches if necessary.

Stir constantly for about two minutes. If they’re part of a recipe, cook

them separately, adding them in at the end to just reheat.

To cook sea scallops: Pat

them dry as for the bay scallops, above. They can be cooked as is, or

lightly dredged in flour (Wondra works especially well) or even in

freshly cracked black peppercorns. They should be put into a very hot,

lightly oiled skillet in a single layer and not overcrowded. The

scallops should be cooked for just a minute or two at the most, then

turned and cooked for another minute. As above, if part of a recipe,

cook them separately and add just before serving.

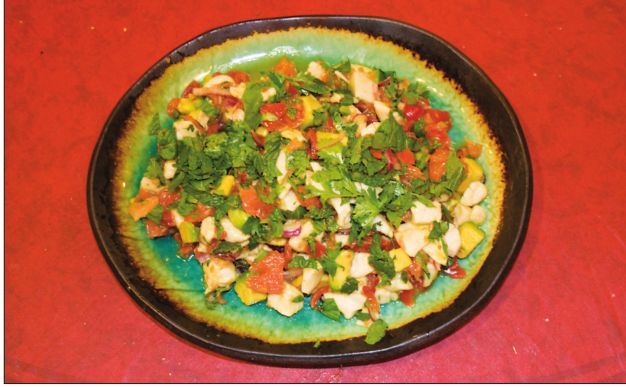

Ceviche with seafood, avocado, and grapefruit

Scallops

are also delectable “in the raw” by themselves or for sushi or in

ceviches. Ceviches, which may be prepared with many kinds of fish and

seafood, are found throughout Latin America but are especially popular

in Peru. The lime juice marinade “cooks” the fish/seafood. They’re a

perfect light dish for summer.

• 1 pound dry-pack bay or sea scallops, or small shrimp, either singly or in combination

• 1/2 cup fresh lime juice, plus more if needed

• 1 cup seeded, finely diced ripe tomatoes

• 1 tsp. habanero hot sauce or to taste, optional

• 1 tablespoon honey

• 1 medium jalepeño pepper, stemmed, seeded, and cut into thin slivers, optional

• 1/2 cup thinly sliced red onion

• 1/4 cup loosely packed cilantro

• 1/4 cup loosely packed mint

• One large or two medium/small grapefruit, preferably pink or red

• One large or two medium/small ripe avocadoes

• Olive oil for drizzling

• Soft lettuce leaves

Seafood for ceviche

should be as fresh as possible. Cut shrimp in half lengthwise. Leave

tiny bay scallops whole; cut larger ones in half crosswise. Cut sea

scallops into thin slices or small dice; this is easier to do if they

are partially frozen (10 to 20 minutes in a single layer in the

freezer).

Combine the

seafood with the lime juice in a bowl or resealable plastic bag and let

it stand until the seafood turns opaque, about 30 minutes. If you are

using two kinds of seafood, it’s best to marinate them separately (which

may require additional lime juice), because their “cooking” times may

differ.

Soak the onion

in salted water (1 tablespoon salt dissolved in 1 cup water) for 20

minutes, then drain it and squeeze it dry. Mince half of the herbs and

tear the rest into pieces.

Combine

the tomatoes, hot sauce, honey, jalapeño and minced herbs in a large

bowl. Add the onion and mix gently. When the seafood is opaque, drain it

well, add to the bowl, and toss the contents gently. The ceviche may be

refrigerated for as long as four hours at this point.

Cut

each avocado in half and twist to separate the halves, then remove the

pit. Cut the rind off the grapefruit with a large sharp knife, being

careful to remove all of the bitter white pith. Remove the grapefruit

sections from their casings, then discard the casings and seeds.

The

grapefruit and avocado can be cut into bite-size chunks and mixed in

with the ingredients in the bowl, or the grapefruit can be left in

sections and the avocado cut into thin slices for a “composed”

presentation. For each serving, lay a lettuce leaf on a plate or use a

handful of baby lettuce leaves. Divide the ceviche among the plates. If

you are using whole grapefruit sections and avocado slices, arrange them

decoratively around the mound of ceviche on each plate. Drizzle the

dish with olive oil and scatter the remaining herbs on top. Serve

immediately. Serves four to eight.

This

recipe may be prepared as long as four hours ahead (refrigerate if not

serving immediately), except for the avocado, which should be added just

before serving. It can also be used as a dip with tortilla chips:

Eliminate the grapefruit and cut the seafood and avocado into medium

dice and the onion into fine dice.

Contact Julianne Glatz at [email protected].