Might immigrants come to America to farm our universities?

DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

I have often lamented here the continuing decline in the population of Illinois’ rural parts. (See “Devoid of life,” July 14, 2011.) Like a great many readers, I have roots in central Illinois that go deep. My interest in the central question – if the present population cannot support itself on the countryside, how might we replace it with one that can? – is not mere wonkery.

The U.S. has always had more land than it has good uses for it – look at Indiana – so bringing people and land together has long been an urgent aim of federal and state policy as far back as 1812. Congress set aside lands it had swindled from Native Americans in the then-still remote West as a reward for soldiers who had volunteered against the British in that war. Some of that bounty land lay in the future State of Illinois between the Illinois and Mississippi rivers.

In the decades that followed, federal policy was geared to aid those who wanted to become rich, not only those who already were.

Congress offered quarter-sections of public land for sale at $1.25 an acre to encourage settlement. My ancestors trekked all the way from Upper Saxony to Cass County to take advantage of the offer in the 1830s; thus capitalized at the public expense, they built families and small fortunes and returned the investment many times over in taxes.

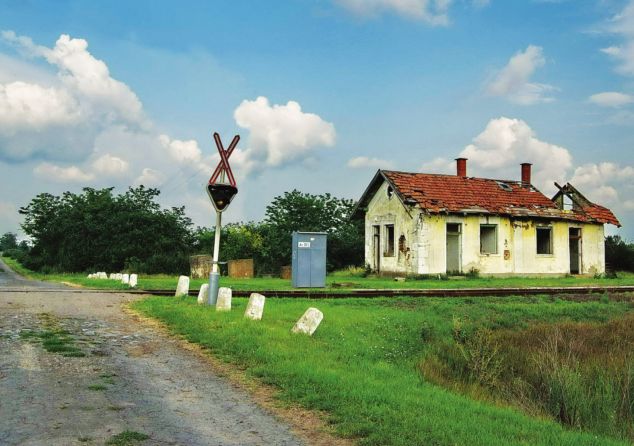

In 1851 the federal government gave newly-chartered Illinois Central Railroad nearly 2.6 million acres of publicly-owned land along the proposed route. To defray construction costs the company sold much of it to settlers; the IC also founded dozens of new towns along its tracks in demographically barren east central Illinois, including Champaign, Mendota, Sublette, Amboy, Rantoul, Pesotum and Tolono.

There was a modest and short-lived return to the Illinois countryside during the Great Depression by former farmers returning from jobless cities. (A branch of my family came back to Cass County, for example, when jobs in the Chicago area dried up.) There was a very much smaller, and very much less serious back-to-theland “movement” in the 1970s when disaffected young people went into the hills of deep southern Illinois in search of authenticity, self-sufficiency, independence from a corrupt and corrupting commercial culture and the freedom to smoke dope. (Not much of that settlement happened in central Illinois. Any hippie who laid down in a field to take a nap while hitchhiking to California would have been plowed up and planted in beans in this part of the state.)

Making a living from the land is not work that many of today’s young Americans want to do. My grandparents were far from unusual in having had to learn to run and repair farm machinery, can foods, sew clothes, butcher and clean food animals. Give a typical American 40 acres today, and the only way he knows how to make a living from it is to flip it.

In less favored lands, however, are many eager land-hungry emigrants. Repopulating the countryside with farmers from India or Africa or South America would resurrect a farm economy of a kind not seen in Illinois for decades – small operators who rely on human rather than imported energy and which produce small surpluses for mostly local sale. It would also vastly improve the restaurant fare in our small towns.

Unlikely? A Kenyan in Christian County is no less likely that a Punjabi in Lombardy. In that part of Italy, young people no longer take up their parents’ craft of making Parmesan cheese. That there is still plenty of Parmesan on Italian salads owes to the Sikh immigrants who are doing more and more of the work, and owning more and more of the companies.

Informed readers will have already noted that during each of the episodes I describe, land in rural Illinois was cheap. Alas, only those who already own central Illinois farmland can afford to buy any more. But a different class of immigrant is eager to fill in the blank spaces in our countryside that cannot be farmed profitably – the middle class of newly-emergent economies. The lure for them is not land but education. A group of Chinese investors reportedly wants to build 400 units of housing in rural Michigan about 20 miles from Ann Arbor. The high-end houses would be designed specifically for Chinese immigrants looking to qualify their kids for in-state tuition rates at the University of Michigan. You’ve heard of labor camps and mining camps. Why not education camps?

Illinois would need Washington to tweak the immigration rules to make it possible to add a few New Beijings to our New Berlins. Congress voted billions in ethanol support that is killing the Illinois countryside. Spending nothing to help bring it back to life is the least it can do.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Editor’s note

The closing of St. Joseph’s school after 136 years of operation on Springfield’s north end (see p. 17) is a loss to the community gone largely unexamined. As Catholic education declines across the country, St. Joseph’s closing was seen here as inevitable, so nobody fought it much, concentrating energy instead on celebrating the school’s rich heritage. Yet before other Catholic schools close, there should be a pause to ask why funding from the church is declining, and enrollments are dropping in Springfield’s older neighborhoods, even as nearby bedroom communities struggle to build new schools fast enough to keep up with demand. In other cities, struggling Catholic schools have been made into charter schools, or given a fresh mission with marketing and philanthropic support. As demonstrated by St. Patrick’s school on the east side, there is still a role for the church to provide excellent elementary education for children, although Springfield’s oldest Catholic school will no longer be around to help. –Fletcher Farrar, editor