Can Springfield turn around its languishing public schools?

EDUCATION | Patrick Yeagle

Four years ago, a report on education in Springfield revealed some difficult realities about the city’s public schools. The report highlighted declining test scores, poor attendance, low graduation rates and inadequate college preparation – problems shown to be even worse among African American students.

Since that 2008 report was published by the City of Springfield’s now-dormant Office of Education Liaison, the situation doesn’t appear to have improved much. In 2011, 84 percent of African American high school juniors failed a state reading exam, while 82 percent failed the math portion. Nearly a quarter of all high school students who should have graduated in 2011 instead dropped out.

The disheartening statistics are endless, but that’s not unique to Springfield, says Shelly Heideman, executive director of the Springfield-based Faith Coalition for the Common Good.

“Things are bad all across the U.S.,” Heideman says, referring to low test scores nationwide and statewide. “In every community, it’s the same story. There has to be something in the system that needs to be changed.”

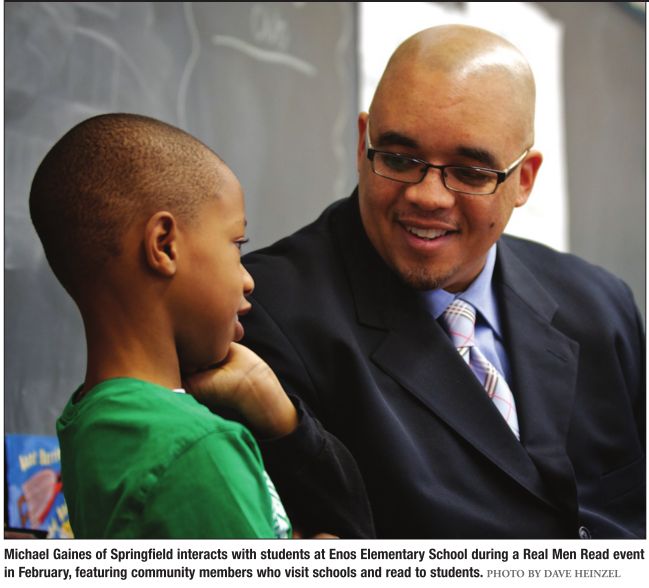

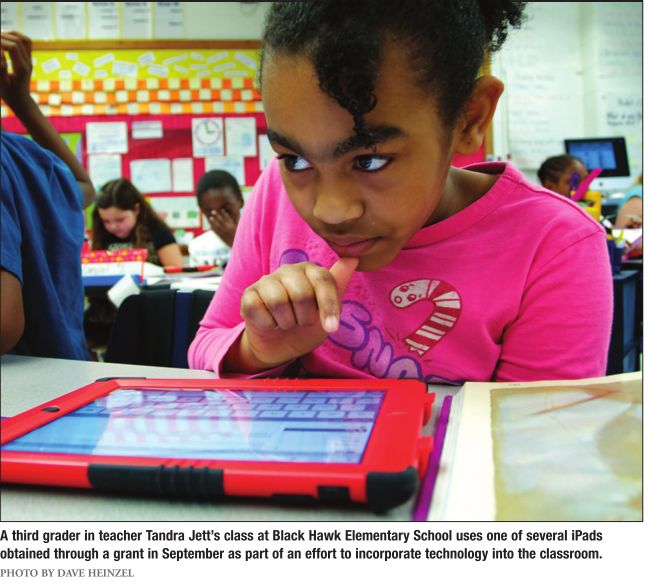

While test scores remain low, the district has undertaken several efforts – both independently and with help from the Faith Coalition – to motivate students, improve parental involvement and communication, and help teachers do more in better schools.

“We can’t just blame the school district or teachers or parents,” Heideman says. “It’s all of our responsibility.”

District 186 vs. Illinois Evaluating a school district often involves comparing the district’s standardized test scores with the rest of the state. While students in Springfield Public Schools have consistently tested below the rest of the state over the past decade, the rate at which students in this district pass state standardized tests has increased over the same time frame, from 52 percent in 2002 to 68 percent in 2011.

But Faith Coalition member Paula Stadeker says standardized tests may not provide an accurate assessment of a district’s ability to educate kids. One common criticism of standardized tests is that they typically don’t account for cultural differences in learning that may affect scores.

“It’s bad in the sense that 84 percent is a lot of kids to not be meeting the standards,” Stadeker said, referring to the rate at which African American juniors failed the state reading exam in 2011. “But we have to look at whether the standard is measuring their true ability in light of their socio-economic circumstances.”

Howard Peters IV, spokesman for the Springfield Urban League, agrees that the low test scores alone don’t tell the whole story. The Urban League co-wrote the 2008 education report and is part of the Faith Coalition.

“If you’re just looking at the numbers, it’s difficult to find a ray of light in there,” Peters says. “But it appears the district is certainly on track to address these issues. These are not the kind of issues you can see changed in a single school year. This is about a strategic plan of turning around our education system, and I think the district has made strides to do that. It’s about capturing students at a young age and fostering a motivated passion for learning.”

Challenges and changes It’s in that long-term mindset that the district and the Faith Coalition are working to improve education in Springfield.

Chronic truancy has long been a source of concern, says district spokesman Pete Sherman, adding that the district has a truancy task force working on solutions. A student is chronically truant if they miss 18 school days without a valid excuse. The situation seems to have improved in 2011, when only 369 students were deemed chronically truant. That’s about 2.6 percent of the daily average attendance, and it’s a decrease from 591 truant students in 2010.

“We have to give kids a reason to want to come to school,” said District 186 Superintendent Walter Milton at a Feb. 25 education summit hosted by the Faith Coalition. To get more kids coming to school, Milton is pushing for a community-wide approach that would increase accountability for students who skip school and the parents who let them do so. Milton wants to implement random city-wide truancy sweeps to round up students who should be in school but are instead walking the streets. The sweeps would use the combined forces of police, firefighters and local businesses to locate and report truants.

“We did it in Flint, and it worked,” Milton said, referring to truancy sweeps in Flint, Mich., where he was superintendent before taking over at District 186 in April 2007. As part of his plan, parents could receive a court summons to explain their child’s truancy to a judge after repeated incidents.

To supplement the district’s efforts, the Faith Coalition formed a committee that plans to talk to students to find out why they skip school.

“If kids aren’t at school, they can’t graduate,” Heideman says. “They end up in lowwage jobs or even in prison. … I know of one student who skipped school for two months. Imagine how much you’d miss in two months, how far behind you’d fall.”

Peters says it’s important to get children hooked on education by the fourth grade, or else they’re in danger of fading from school and eventually dropping out.

“You have to find a way to connect with them so they have their own fire and you’re just stoking it for them,” Peters says. “We have to build competitive, interested and motivated students who go home and get their whole family interested in education. Parents these days have so much on them. It’s difficult to expect a mom to work 12 hours and then come home and help her kids with their homework. It’s about turning little Johnny into the self-starter.”

The Faith Coalition held listening sessions during summer 2011 to meet with district parents and hear their concerns. Among the concerns raised was a lack of communication by the district. Faith Coalition member Susan Eby says some parents felt like teachers “talked down” to them or “talked over their heads.” Eby praised the district for three initiatives already in the works to improve communication with parents.

Among those improvements is the implementation of Family and Community Engagement (FACE) teams composed of parents from each school. The FACE teams allow parents to have input in district decisions, get involved in projects and share information more easily.

To connect parents with academic and personal support systems for their children, the district has Parent Educators in schools with high poverty rates. That’s becoming increasingly important because the percentage of low-income students has risen consistently over the past decade, to the current level of 67.2 percent. Studies show students from low-income households tend to struggle in school, possibly due to instability or stress at home, inadequate nutrition, overworked parents or similar factors.

The district also has a Parent Mentor who helps parents of children with disabilities understand special education and support services.

To further improve communication with parents, the district and the Faith Coalition are together examining ways to make the district’s disciplinary handbook more clear. The district is also working on website improvements to make information more current and easier to find. Pete Sherman, spokesman for the district, says most of the website revisions will be made this summer.

Kathy Crum, the district’s director of teaching and learning, says the district is constantly helping teachers better themselves through professional development.

continued on page 14