HISTORY | Tara McClellan McAndrew

Springfield is known as the home of Abraham Lincoln, but a man from Lincoln’s neighborhood gets short shrift in our city’s legacy.

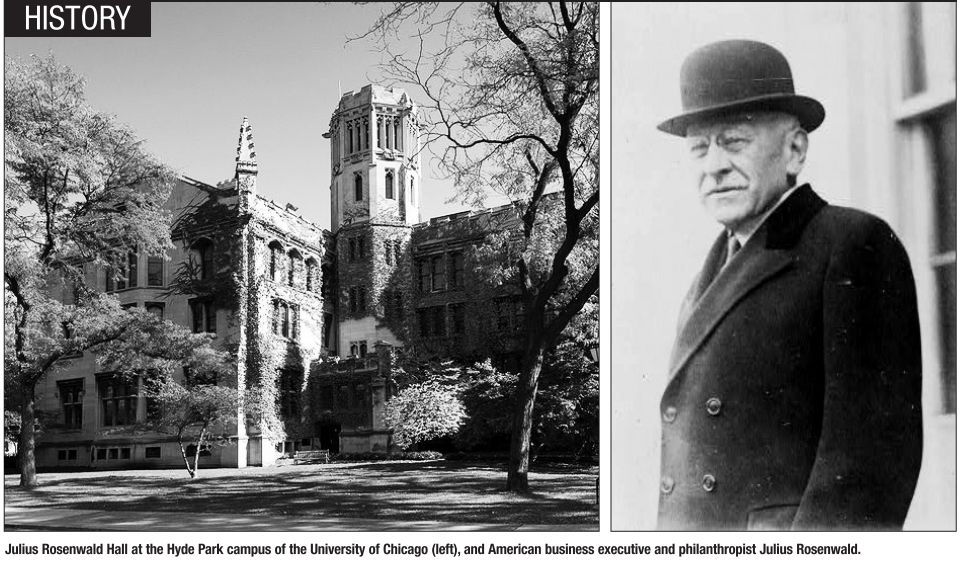

Julius Rosenwald was born a block from Lincoln’s home in 1862 (where the Lincoln Home’s main parking lot is now) and became one of America’s greatest businessmen and philanthropists of the 20th century.

Rosenwald is credited with making Sears the country’s top retailer after joining the firm in 1895 and with donating millions to correct society’s ills and injustices.

Julius’ father, Samuel, was a Jewish German immigrant who came to Springfield in 1861 to manage the Hammerslough Brothers’ store on the north side of the downtown square, according to Julius Rosenwald by Peter Ascoli (Indiana University Press, 2006). The clothing store sold Civil War uniforms and business was growing.

In May, 1865, when Lincoln’s funeral was held here, the store sold 30,000 mourning badges, according to a 1969 report from the Lincoln Home National Historic Site. Business continued to increase, as did the Rosenwald family. By 1868 there were five little Rosenwalds, so the family moved into a larger house at 413 South Eighth Street – across the street from Lincoln’s home and slightly north of it. Lincoln owned this lot at one time.

On Oct. 15, 1874, a 12-year-old Julius got what might have been his first taste of retail here. The occasion was the dedication of Lincoln’s Tomb. He earned $2.50 by selling pamphlets and lithographs of it, according to Ascoli. President U.S. Grant spoke at the dedication and Julius shook his hand.

What made the biggest impression on him was Grant’s yellow kid gloves because he’d never seen any before.

The Rosenwalds were active in Springfield’s Jewish community and attended “Congregation B’rith Sholem” where Samuel was president for seven years, Ascoli writes. A year after Julius’ bar mitzvah, the congregation “dedicated a new Reform temple.”

In 1877, Julius got his first job. It was another retail gig at a “99 cent store” in Springfield, “where everything was either 49 cents or 99 cents,” according to Ascoli, who quoted from Julius’ short autobiography. Rosenwald’s duties included delivering a croquet set and a glass bowl with two fish.

That job came during a break from Julius’ two years at Springfield High School, located at Fourth and Madison Streets. That was the highest level of education he attained, which bothered him throughout his life, according to his biographer. Perhaps that’s one reason he later helped fund a variety of educational programs, including medical schools, universities and more than 5,000 schools for African-Americans.

Julius left Springfield in 1879 for a bigger market. He went to New York City to work for his uncles, who were manufacturing clothes. Six years later he moved to Chicago and operated his own clothing store.

By 1895 his store was making clothes for Sears, a company that his brother-in-law wanted to invest in, but needed someone to help. The brother-in-law asked Julius if he wanted to split a quarter share in the new mail-order firm. Julius did and ended up leading the company years later.

When Rosenwald joined Sears in 1895, it had the perfect clientele – rural dwellers who didn’t have access to stores. But it lacked an efficient, organized system to meet their demands. Julius successfully systemized the store’s ordering process and later moved the company into brick and mortar stores. His long tenure there (which ended in 1932 when he chaired the board) made him a very wealthy man.

While he was the president of Sears, he established his own philanthropy to give some of that money away. The Julius Rosenwald Fund’s aim was to help the “wellbeing of mankind,” according to the website of the University of Chicago, which he supported and where he bequeathed his papers.

“He applied his philanthropy to pioneering efforts in order to stimulate action and eventual responsibility by those more directly concerned.”

Rosenwald once said that choosing the recipients for his funds was a harder task than earning them. He helped establish the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago as well as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He built housing for the poor, supported early birth control efforts, helped the Tuskeegee Institute and much, much more.

Rosenwald’s efforts were at least partly inspired by his hometown’s hero, Abraham Lincoln, whom he considered “America’s greatest man,” Ascoli writes, quoting one of Rosenwalds’ children. Sadly, Rosenwald never met Lincoln. Lincoln was already in Washington, D.C., serving as president when Rosenwald’s parents moved to Springfield.

Contact Tara McAndrew at [email protected].