FILM | Chuck Koplinski

Along with Hugo and Drive, also 2011 releases, Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist is a film steeped in the history of American cinema. With nods towards A Star is Born, Citizen Kane and Singin’ in the Rain as well as the life of silent film star John Gilbert, the movie is a loving homage to the golden age of cinema. But what makes the film great fun is that Hazanavicius has fashioned a perfectly rendered melodrama, the kind that were the film studios’ bread and butter during the 1920s, a product that audiences ate up like candy.

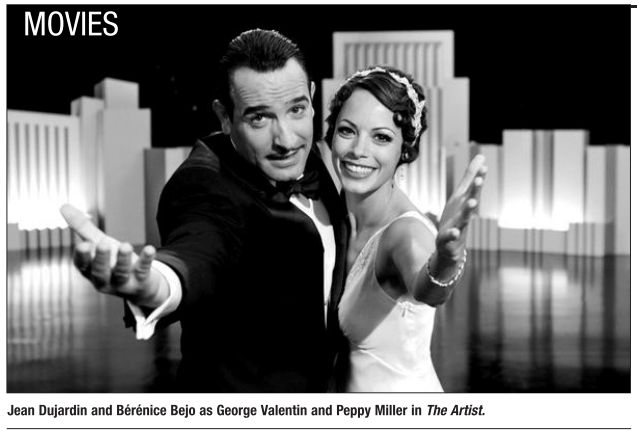

It’s 1927, a crucial time in the history of cinema, when the Hollywood studios are on the cusp of converting to sound films. However, the biggest star of the silent era, George Valentin (Jean Dujardin), is oblivious to this radical change. He’s just released his latest lighthearted adventure film, which is destined to be a hit. Secure in his wealth and fame, the actor doesn’t have a worry in the world, unless you count his dissatisfied wife (Penelope Ann Miller), who spends her time sulking about in their mansion. However, this Tinsel Town dream soon comes to a halt when the head of Kinograph Films (John Goodman) informs Valentin that all of their films will now be sound features, a piece of news that prompts the star to quit and produce his own movie, yet another silent adventure.

As Valentin’s star fades, that of Peppy Miller (Berenice Bejo) rises. Having met by chance at a movie premiere, their paths continue to cross as the trajectory of their careers move in opposite directions. There’s an undeniable attraction between the two, a feeling that continues to grow even when Valentin winds up nearly homeless, a victim of his own hubris as well as his refusal to change with the times.

For those familiar with the silent era and Hollywood history, this movie will be a delight. It captures the innocence of the dawning days of the American film industry as well as the aesthetic of the movies of that era. The black-and-white cinematography by Guillaume Schiffman is beautifully crisp and clear when telling Valentin and Miller’s story and appropriately grainy when we see the films they star in. These wonderful throwback images are bolstered by Ludovic Bource’s score that perfectly duplicates the wild changes in tempo that were part-and-parcel of silent films, while frequent montages remind us of the wonderful economic style of movies from this era.

The film’s cast provides the final piece of the puzzle here, providing broad but heartfelt performances that mirror the era. However, Dujardin and Bejo are able to convey the inner turmoil of their characters with a downward glance, a quick smile or an offhand action, all of which speak volumes. Dialogue isn’t necessary for them and we can’t help but feel for both of them, as each is able to project a winning degree of innocence. In supporting roles, James Cromwell as Valentin’s faithful chauffeur and Missi Pyle as a vain starlet both register as well, making the most of their limited screen time to carve out distinctive characters and moments.

More than anything, The Artist proves the old maxim “everything old is new again.” In taking the medium back to its roots, Hazanavicius succeeds in reminding us that films are able to weave a wondrous spell without the “benefit” of special effects. As always, sympathetic characters and a compelling story are all that are needed to create movie magic. Here’s hoping The Artist fosters a renewed interest in silent films and moviegoers will seek them out. The wonders they contain need to be enjoyed once more.

For Chuck’s review of Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy go to illinoistimes.