Local banks didn’t cause the financial crisis, but they pay for it through increased regulation

BANKING | Patrick Yeagle

It could have been avoided.

The housing crash, the widespread home foreclosures, the credit crisis, the rampant bank closures, and ultimately the Great Recession of the past four years never had to happen.

That’s the message of a 439-page report from the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, the study group appointed by Congress to figure out what caused the Great Recession.

The crisis was caused mainly by a combination of poorly-vetted “subprime” mortgages bound to fail, complex financial instruments that hid bad loans, excessive borrowing and lending by large banks, and a poor understanding by federal regulators of the system they were supposed to oversee.

The commission is clear that blame for the crisis rests on many heads: lax and unprepared financial regulators, dishonest mortgage brokers, and even homeowners who fudged their income on mortgage applications, to name a few. But a hefty share of that blame is reserved for large commercial banks.

Some of those banks only became well known to the average person because of the crisis – Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs and more. Most people outside the investing world likely never have contact with these financial firms, or “shadow banks,” because they concentrate mostly on complex financial trades for large businesses.

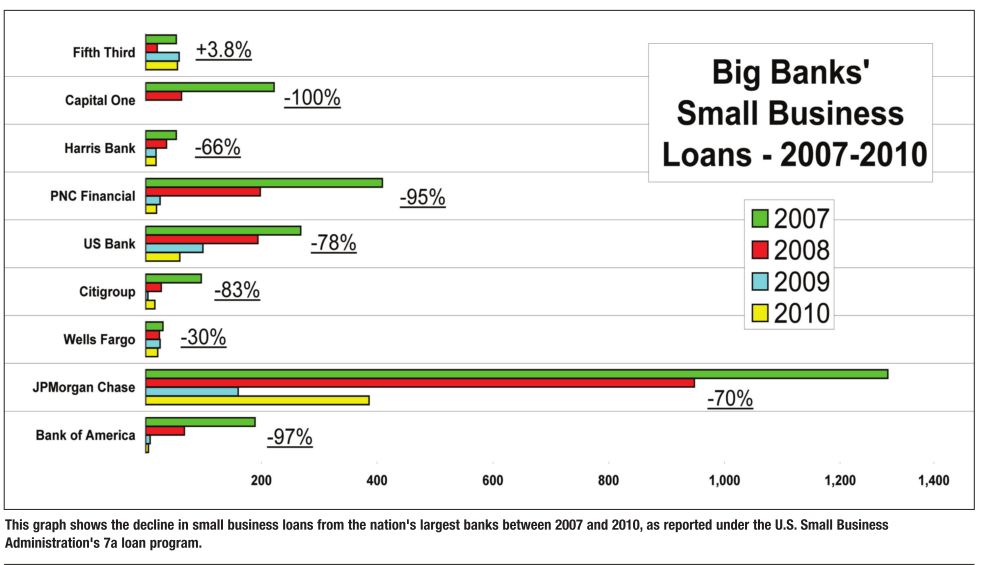

However, some of the banks that share the blame are household names, like Bank of America, JPMorgan Chase, Citigroup and Wells Fargo. These large regional banks offer common banking services like home loans and savings accounts to individuals and businesses. Although they aren’t primarily investment firms, they invested heavily in risky stock market speculation.

But there’s another player in the commission’s report, one that isn’t assigned a share of the blame. In fact, this other element provides the type of “told-you-so” admonishment that seems so sensible in hindsight. It was the community banks – relatively small locally-owned and operated banks – that warned consumers about the perils of over-borrowing and warned regulators of impending financial trouble. Though community banks offer consumer banking services similar to those of large regional banks, the community banks’ aversion to risky speculation allowed them to maintain a clear-eyed perspective while visions of vast profits led their larger counterparts astray.

“Veteran bankers, particularly those who remembered the savings and loan crisis, knew that age-old rules of prudent lending had been cast aside,” the commission noted. “Arnold Cattani, the chairman of Bakersfield, Calif.based Mission Bank (a community bank), told the Commission that he grew uncomfortable with the ‘pure lunacy’ he saw in the local home building market, fueled by ‘voracious’ Wall Street investment banks; he thus opted out of certain kinds of investments by 2005.”

Andrea Cusick, senior vice president of communications for the Community Bankers Association of Illinois, says the crisis held a “silver lining” for community banks.

“Politicians, the media and the general public finally started to understand the difference between the community banks and mega banks,” Cusick said. “We’re not all the same animals, and it was pretty obvious that it wasn’t us who caused the crisis.”

“We didn’t start the fire”

Why didn’t most community banks join big regional banks in the type of imprudent loaning and speculative trading that caused the crisis? Micah Bartlett, president and CEO of Town & Country Bank and the bank’s holding company in Springfield, says community banks simply have a different business model.

“In a big bank, consumer banking is very product-driven and commoditized, and they have to do everything the same way,” he says. “In a community bank, our business is really relationships and stories and nuances – being part of the local fabric of the community.”

Robin Loftus, executive vice president of Security Bank in Springfield, said risky investments just aren’t what her customers want or need.

“We’re not involved in derivatives, and frankly, I wouldn’t even know what do with them,” she says with a laugh. “We do mortgages, auto loans, deposit accounts. We know our customers and understand our customers.”

She says a bank regulator once questioned her about home loans with the same suspicion sometimes directed at large regional banks.

“He said, ‘You’re telling me you never put someone in a house they couldn’t afford?’” she said. “I replied ‘No! We have to live with these people and face them on the street.’ Sometimes we’ll tell them it’s not the right time to buy, and though some may be angry at first, they usually come back later to thank us and say they’re in a much better position. The last thing we want to do is take someone’s home through foreclosure.”

Pat Phalen, president and CEO of the holding company for Illinois National Bank in Springfield, says INB makes its money “the good old-fashioned way” – through traditional banking activities.

Phalen is a former bank examiner for the Illinois Department of Financial and Professional Regulation, which oversees banks that have state charters. INB has a national charter, meaning the bank is authorized under federal law rather than state law. He says community banks are inherently conservative with money, and speculative trading holds too much risk.

“Ultimately, it doesn’t help the community,” he says of risky investing. “It’s not at the core of why we’re here, and that’s providing service to our customers.”

Robin Loftus says she has spent most of her career at community banks. After a short stint working for a regional bank early in her career, she found that she much preferred working at community banks because of the local control.

“When you can’t make decisions on-site, when you have to deal with people in another state to make decisions…I don’t feel like you’re effective at doing your job and taking care of your customers as you should,” Loftus said. “Decisions at big banks are made at much higher levels, and it’s just not the same.

“When a customer walks into my bank and they want to speak to the president, his office is on the first floor, and he has his door wide open. If someone’s upset or happy, they can walk right into his office and talk to him. You can’t do that at Bank of America. You’re lucky if you get anybody to talk to you at a big place like that.”

Mike Pence, executive vice president at Bank of Springfield, said community banks have the advantage of being “nimble.”

“If you have a large loan request, at larger banks that might have to be funneled up through various ladders in the organization,” he said. “We can make a decision between our president and chairman immediately if need be. If a need is there to be reactive, we can certainly provide that, regardless of what it is.”

One size doesn’t fit all

Although community banks didn’t cause the financial crisis, they say reforms aimed at regional banks have actually hurt community banks unintentionally. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, signed into law in July 2010, contains sweeping changes to banks and the financial industry as a whole. David Schroeder, vice president of federal government relations for the Community Bankers Association of Illinois, says it was “inevitable” that the federal government would have to step in as the crisis unfolded.

“The abuse of discretion was so egregious, severe and disgusting that there was no way whatsoever there would not be a vigorous congressional response,” he said.

Schroeder says the law does recognize the differences between large regional banks and community banks, but many of the provisions apply to both types of banks and put an unreasonable burden on community banks.

One example is thick stacks of forms to be filled out and submitted to regulators for every loan, meant to ensure the loans are legal and are properly administered. The problem with that regulation, Schroeder says, is that community banks didn’t engage in the shady loan practices that prompted the reforms, such as encouraging false income information on loan applications and misleading borrowers about their interest rates. Many community banks don’t have enough staff to handle reams of paperwork for numerous loans, so the regulations will limit how many loans community banks can issue, he says.

Mike Pence at Bank of Springfield said community banks are “paying the price for other peoples’ mistakes.”

“Our bank has never had any issues in terms of lending or providing inaccurate information to get them approved,” he said. “It’s just not the way we operate.”

Amar Bhidé, a business professor at Tufts University in Medford, Mass., takes criticism of the reforms a step further. Bhidé’s recent opinion article in The New York Times urges lawmakers and regulators to “Bring Back Boring Banks” – a call to separate risky speculative trading from commercial banking activities. Bhidé, an author of several books on busi Roundtable, a trade group representing large financial institutions, says the big banks mostly support the reforms.

“It modernized the regulatory framework, helped strengthen the financial institutions and prompted a number of market reforms that were outside of the law,” he says, adding that many of the big banks and financial firms have done away with the practices that contributed to the financial crisis.

Still, Talbott says, the big banks are working closely with regulators to implement the reforms.

“We don’t oppose the bill or want to repeal it, slow it down or kill it,” he says. “We would like to fine-tune it to ensure the goals are met in either the most cost-effective way or in the least damaging way.”

Talbott also points out that not all big banks played a role in bringing about the financial crisis.

“There was plenty of culpability to go around, but it’s difficult to paint one part of the industry or sector with a broad brush,” he says.

“They’re all over the spectrum. Each bank stands alone.”

One example of a large regional bank that didn’t seem to play much of a role in the crisis is PNC Bank, which has 2,500 locations in 15 states. Frederick Solomon, a spokesman for PNC, cautioned that while PNC is careful not to act as the “spokesbank” for the industry, his bank “did not have a significant mortgage origination business when the recent financial crisis started.”

Christine Holevas, a spokeswoman for JPMorgan Chase, said she and the bank’s leadership understand that “people are frustrated” with the financial crisis. Though Holevas is stationed in Chicago, she came to Springfield to meet with Chase employees and discuss their concerns.

“Those people live in the same neighborhoods as everyone else,” she said. “They go to those schools and go to those supermarkets. They want to do the right thing.”

When protest groups like Occupy Wall Street appear at a Chase branch, Holevas said a bank representative meets with them to hear their message.

“Someone goes out and talks to them because they want to be heard,” she said. “Usually, they have a specific issue, and we will work with them to try and solve it. They’re not always going to get the answer they want, but at least someone is looking at it.”

Banking on the community

While community bankers in Springfield tout their commitment to philanthropy and reinvestment in the community, some large regional banks also support charitable causes and expect employees to volunteer.

Each of the community banks interviewed said charitable giving is a priority, and each said they encourage their employees to volunteer and financially support charities. Several of the community bankers themselves also serve in leadership roles for the United Way, Red Cross and other charities.

Sarah Phalen, president and CEO of Illinois National Bank in Springfield, says INB encourages employees to give their “time, talent and treasure” to good causes.

“We’re a family here, and we’re working together for a good cause,” she says.

But big banks say they also make giving a priority.

Christine Holevas at Chase says the bank supports the local efforts of TSP Hope, the Lincoln Library Foundation, the United Way, the Hope Institute for Children and Families, and others.

“In Illinois, we have a very robust philanthropy scheme,” Holevas says. “We have a history with them (the charities).”

Chase also offers grants for education, housing and community development.

“It’s all available through our website, and a real person will contact you,” Holevas says.

Bank of America spokeswoman Diane Wagner says her bank gave away more than $12.4 million in grants to charities in Illinois last year. While Bank of America doesn’t have a branch in Springfield, Wagner says the bank’s branches in Chicago provide grants for affordable housing and free tax preparation for lowincome families, along with fundraising opportunities through the bank’s sponsorship of the Chicago Marathon.

While community bankers are eager to differentiate themselves from their larger counterparts, they are quick to defend local employees of big banks.

Pat Phalen at INB says many of the bankers and tellers in Springfield have worked together at some point in their career.

“We’ve worked with people at any of those three bigs in town (Chase, U.S. Bank and PNC), and there’s good people there,” he says.

Robin Loftus at Security Bank agrees. “I don’t ever want to say that the people working locally at Chase are not good people,” she says. “I don’t want to criticize them, because I know them, and they’re good people.”

Christine Holevas at Chase says it’s important to remember that big banks draw staff from the same communities they serve.

“The face of the bank is usually someone who lives in your neighborhood,” she says. “They’re just like you. Let’s not forget that.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].