Springfield is saturated with great places to work out. That’s good for your bottom line.

FITNESS | Bruce Rushton

Old city directories and phone books tell the story.

Thirty years ago, fewer than five health centers, fitness clubs, gymnasiums – pick a noun – did business in Springfield. Twenty years ago, there were fewer than ten.

Today, nearly 20 fitness centers in the Springfield area troll for customers in the yellow pages.

“It’s extremely competitive,” says Maureen Suhadolnik, executive director of Gold’s Gym on Clear Lake Avenue. “For the size of this town, there is an incredible number of gyms and fitness centers. It’s insane.”

There are plenty of would-be customers out there. Check out any buffet line, and if you don’t believe your eyes, consider a report published last summer by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Trust for America’s Health, which found that Illinoisans were the 15th least physically active folks in the nation. Researchers found that the percentage of obese people in Illinois is increasing, with the state ranking 23rd when it comes to obesity rates. Between being obese and just plain overweight, nearly 64 percent of us need to do something, according to the study.

Collectively, Americans need to lose 4.5 billion pounds, the surgeon general warns. But just 16 percent of Americans over the age of 6 belong to fitness centers, according to the International Health, Racquet and Sportsclub Association (IHRSA).

Fitness has been a growth industry during the past decade, regardless of high unemployment, stock-market crashes and mortgage messes. Since 2005, membership in health clubs has grown from 41.3 million to 50.2 million people, with membership dropping in just one year, 2007, according to the IHRSA. With figures like that, it shouldn’t be surprising that the number of health clubs has also grown, from 26,830 to 29,890 during the same time period. Same-store revenue increased by 1.5 percent in 2010, with total industry revenue increasing by 5.9 percent.

Illinois, which has seen a decrease of nine percent in the number of health clubs since 2007, is bucking the trend. But not the Springfield area.

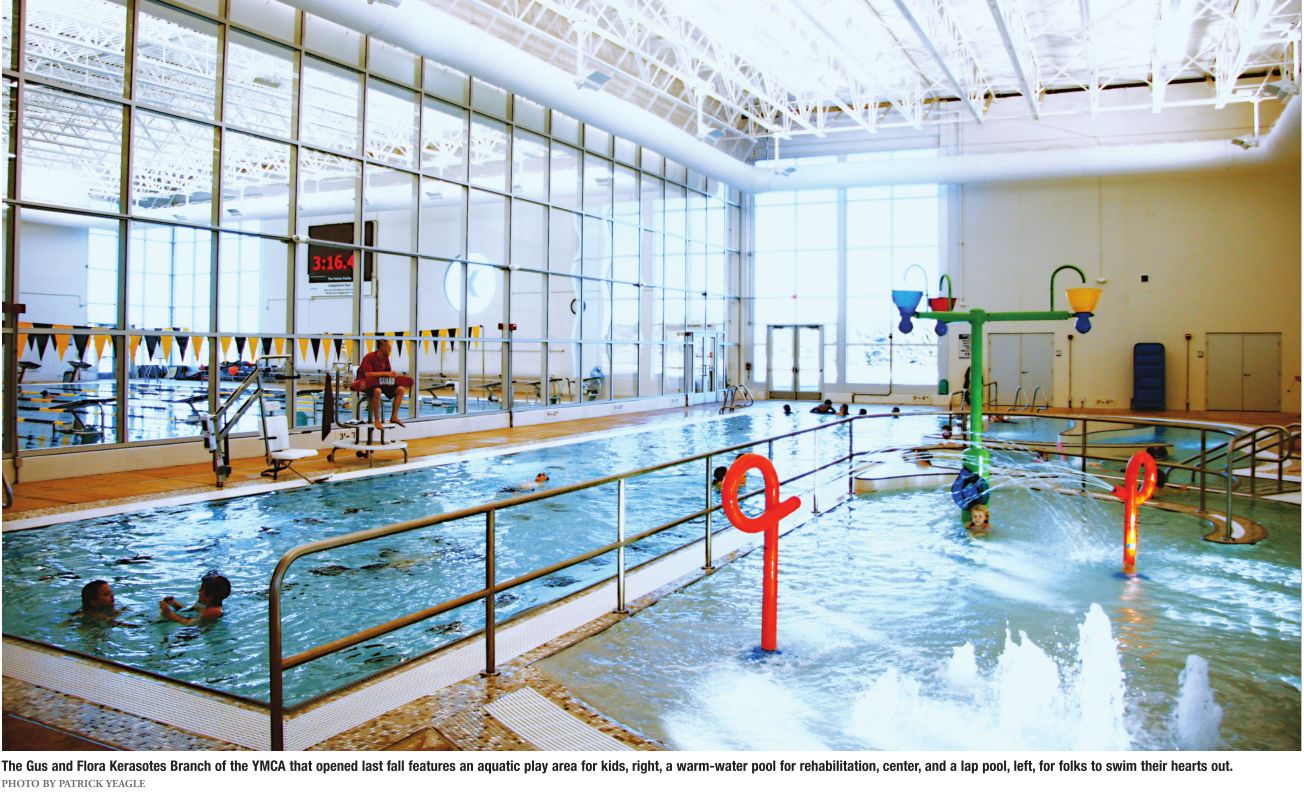

A new YMCA opened on the west side of Springfield in November, with Memorial Medical Center contributing $8 million of the $18 million in construction costs and Tony Kerasotes, head of Kerasotes Theatres, kicking in another $2 million for the center named after Kerasotes’ grandmother and grandfather. FitClub wants to build a fitness center in Chatham on land owned by the Ball-Chatham School District, which would pay as much as $21,000 per month to use the facility’s pool. St. John’s Hospital would lease space for a sportsmedicine enterprise. The proposed partnership with the school district was placed on hold last fall, however, after parents and members of a group called Schools Not Pools raised concerns about costs to the district.

FitClub already runs three fitness centers in Springfield. Kevin Imhoff, FitClub owner, says there comes a point where enough is enough.

“I really think that the fitness market in general is beginning to be saturated in Springfield, which is why we’re looking at expanding to Chatham,” Imhoff says.

The relationship between St. John’s and FitClub dates back a decade, when the hospital’s sports-medicine arm, called AthletiCare, began leasing space from Imhoff’s company. A joint facility is now located on South Sixth Street, where patients rehab from injuries or surgeries and injury-free athletes undergo assess ments to improve performance.

“It’s a logical business relationship for us,” says Tim Butler, director of marketing for St. John’s Hospital. “St. John’s, and I think the health care industry as a whole, is looking toward preventative measures when it comes to health care. … We want people to live healthy lifestyles.”

While flab might be lucrative for endocrinologists and cardiologists, St. John’s sees opportunity in preventing heart attacks and diabetes by helping folks stay fit. For instance, a runner who develops a training regimen and nutritional program with the help of trainers and other experts at AthletiCare might be prone to brand loyalty and seek help from a St. John’s orthopedist if he suffers a broken bone.

“From a business perspective, if we’re building relationships with people in the running community, if someone experiences an injury, they might look to us,” Butler says.

Call the current fitness-center boom part of an on-again-off-again crescendo that goes back a half-century. President John F. Kennedy resurrected interest in physical fitness that had ebbed and flowed since Theodore Roosevelt, a notorious exerciser, issued an executive order requiring that Marine Corps officers march 50 miles in 20 hours to assure that they would not hold men back in battle. Officers unlikely to be assigned to the field could, upon request, be excused from the marching test, Roosevelt decreed, but would forfeit chances for promotion.

Roosevelt’s fitness fervor didn’t do much long-term good. After he left the White House, one out of three draftees during World War I weren’t fit enough for combat prior to basic training, according to a paper written by researchers at the University of New Mexico, who also reported that nearly half of draftees for World War II weren’t fit enough to fight. One month before he was sworn in as president, Kennedy in 1960 urged the nation to get off its duff in an article published in Sports Illustrated entitled “The Soft American.”

“This is a national problem, and requires national action,” Kennedy wrote. “Now it is time for the United States to move forward with a national program to improve the fitness of all Americans.”

Physical fitness, Kennedy wrote, “is a basic and continuing policy of the United States.” He challenged both Marines and the White House staff to pass Roosevelt’s test by walking 50 miles in 20 hours. After the notoriously rotund Pierre Salinger, presidential press secretary, publicly dodged the challenge, Robert Kennedy, attorney general and the president’s brother, hiked the distance.

Five decades later, Americans are fatter than ever, and getting fatter all the time, regardless of efforts by First Lady Michelle Obama to combat obesity. Researchers have found that children who eat federally subsidized school lunches are more prone to obesity than kids who brown bag it. That shouldn’t be surprising, given that the Government Accountability Office in 2003 found that 75 percent of schools didn’t meet federal standards calling for no more than 30 percent of calories in school lunches to come from fat. More recently, Congress last year waded into the minutia of school-lunch menus with debates over whether tomato paste should count as a vegetable, as urged by pizza-industry lobbyists, and whether French fries are as nutritionally sound as the potato lobby claims.

Being fat, it seems, is as engrained in our culture as Big Macs and horseshoes, which, Imhoff says, are unfortunately good for his business. The counter-weight is growing awareness.

“The health club market has grown since the early 1990s because more and more people realize that exercise is something they have to do to maintain their health,” Imhoff says.

Still, Americans love convenience, and that’s as true for the fitness industry as it is for McDonald’s. IHRSA reports that exercisers won’t drive more than five miles to a health club, which helps explain why so many clubs are popping up.

Anthony Nizzio, owner of Anthony’s One On One Fitness on Wabash Avenue, knows firsthand. When his gym, which recently moved, was at the Wabash curve, he says that some customers complained about a lack of parking – they didn’t want to walk more than 10 yards or so from their cars. Nizzio scoffs at clubs that offer valet parking.

“Valet service at fitness clubs?” Nizzio says.

“C’mon.” Nizzio boasts that his club, founded 25 years ago, was one of the first in Springfield that emphasized personal training, which has become a force in the industry. Revenue from extra services such as personal training and spa time is growing at a faster rate than revenue from dues. There’s no getting around it: Walking on a treadmill or lifting a piece of iron over and over and over and over again is boring. And so clubs constantly reinvent themselves, introducing new things, from stripper poles, to spinning, to Zumba, in order to lure and keep customers in an industry where the average membership lasts four years.

Working in a fitness center isn’t so much different than being a schoolteacher or a bartender, according to Wendy Mundhenke, who eschews the title “manager” at Anytime Fitness on North Dirksen Parkway for the company’s preferred moniker, “Hired To Inspire.”

“It’s a people business,” says Mundhenke, who has worked in Springfield fitness centers for three decades. “It’s getting to know each person, welcoming them. This job isn’t just showing people equipment. You’re a therapist. You’re a mother. You’re a nurse. You’re a person-al trainer. You’re holding hands and spinning plates every single day.” Judi Daniels, manager of Fitness World Health Club in Jacksonville.

Continued on page 12