FOOD |

Julianne Glatz

One of the main reasons restaurant food tastes so much better in America than home cooking,” renowned chef Mario Batali often said on his Food Network show, “Molto Mario,” “is that chefs aren’t afraid to really brown things.” It’s a mantra he repeated on any show in which he browned anything. Batali knows what he’s talking about. Sometimes even beginning professional cooks or bakers fail to appreciate browning and caramelization. Once on the reality TV show “Top Chef,” the contestants had to make a dish based on a color.

The contestant who was given brown was disappointed. “Duh,” I thought. “That would’ve been my first choice.”

Several years ago I stopped at the bakedgoods stand at the farmers market. The breads were handcrafted, but looked as if they should have stayed in the oven longer; their crusts barely darker than their interiors. I decided to overlook that, however, when I spied muffuletta sandwiches. A good muffuletta – a New Orleans creation of various Italian cheeses and cold cuts and piquant olive salad stuffed between crusty round bread loaves – is a thing of beauty. The filling was great: excellent meats and cheeses and exceptional olive salad. But the bread was so pallid, limp and insipid that after just a couple bites I discarded the top – and soon I abandoned the bottom as well, eating only the filling. Why waste the calories?

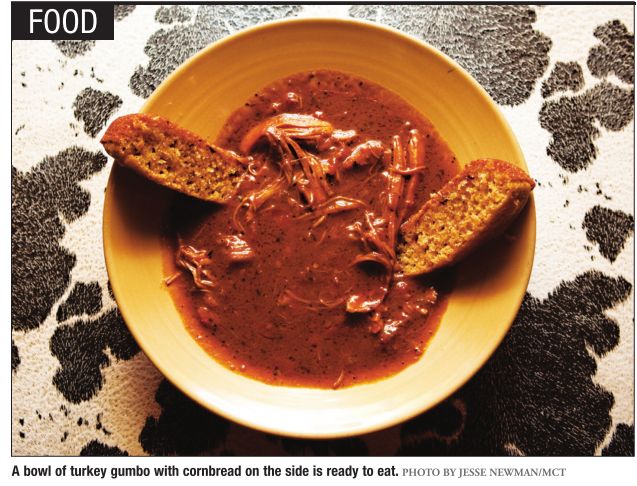

I especially enjoyed demonstrating browning and caramelization when I was teaching cooking classes – not least because of the opportunity for some theatrics. “OK, everybody gather ’round,” I’d say, spearing the meat sizzling in a skillet, “Is this brown enough? No! It’s not nearly brown enough!” Gumbo, however, provided the real drama. There are almost as many variations of gumbo as there are cooks who make it, but all gumbos fall into one of three groups, depending on how they’re thickened: with okra, filé (ground sassafras leaves), or roux. Roux is a classic European mixture of butter or fat and flour, used to thicken sauces and gravies but not really as a flavoring. Louisiana Cajun and Creole cooks “kicked it up a notch,” replacing the butter with oil, and cooking the mixture to increasingly darker shades of brown, with increasingly complex and stronger flavors – from light tan to rich caramel, mahogany and, finally, black. Each shade of roux has specific uses and pairs with specific dishes. The best roux-based gumbos are made with black roux, according to Paul Prudhomme in his classic cookbook Chef Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen: “It takes practice to make a black roux without burning it, but it’s really the right color roux for a gumbo.”

He’s right. I’ve had excellent gumbos made with mahogany roux, but none could match the haunting, almost mysterious flavor of black-roux gumbo. Making black roux without burning it always seems a

bit like playing chicken, but the pressure really intensified when a

bunch of students hovered around me at the stove. “Almost there, almost

there,” I’d mutter under my breath, feeling like Luke Skywalker zeroing

in on his Death Star target. Should I play it safe and throw in the

diced vegetables (which stops the browning) when it was still mahogany?

“No,” I thought, “I’ll risk it.” Just as it turned the color of the

darkest dark chocolate, I made my move. Whew!