Architectural dreams

There are famous buildings, and buildings by famous architects

DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

Springfield’s Trivial Pursuit is not a party game that is much played these days, except by candidates for state representative seats. Several different versions were released over the years in an attempt to broaden the market by narrowing the appeal to, variously, science buffs, movie obsessives or nostalgists. High time, perhaps, for a Springfield version. Here’s a question to start: “Name the four buildings in Springfield designed by famous architecture firms.”

“Famous” in this context means any architect that even newspaper columnists have heard of. Any reader of this paper will be able to name the obvious one – the house on Lawrence Avenue that Frank Lloyd Wright designed for Susan Lawrence Dana. Wright of course is a prominent star in the architectural skies. He gave Dana a better house than she wanted or that the city deserved, and its acquisition for the public by Jim Thompson is a bright spot on the record of a governor whose taste, happily, was much less vulgar than his politics.

The others? One is the building on the Old Capitol square erected to house the old Illinois National Bank. Not the present excellent bank by that name, but the company that wrecked the Orpheum Theatre for a drive-through bank. A lesser sin against building design was INB’s decision to replace the tidy little two-story Art Deco building at Fifth and Washington that was its headquarters after 1950.

Its five-story successor, now occupied by PNC Bank, was designed by one of the stars of the Chicago shop of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill in the early 1970s. That firm designed Chicago’s Sears and Hancock towers, and more recently delivered to Donald Trump a design for his Chicago tower that is, unlike its developer, something that we can dare to look at. The same might be said about the INB project. Sumptuous materials such as polished granite, yes, but otherwise a little bit of suburban office park in the heart of downtown. Its best feature is its atrium – how fitting that that bank’s head quarters should have a symbolic empty space in its heart.

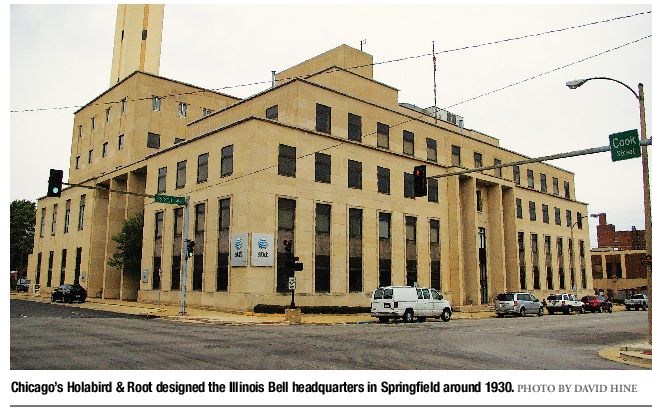

A third building with a pedigree is the Art Moderne headquarters at Sixth and Cook that Chicago’s Holabird & Root designed for Illinois Bell around 1930. That firm did much to make Chicago Chicago. Such iconic structures as Soldier Field, the Hilton Chicago Hotel, the Palmolive Building, Chicago Daily News and Board of Trade Building all came off their drawing boards. The Illinois Bell is not in that league, being an exercise in geometry as much as architecture, but it has its own integrity.

A fourth on my list is the downtown headquarters building that Minoru Yamasaki of Minoru Yamasaki & Associates designed for the Horace Mann Educators Corp. The late Toby McDaniel, the State Journal-Register columnist who spoke for the Springfield Everyman in matters of taste and decorum, pronounced the building “an architectural dream” at its debut in 1972. For what is basically a box filled with desks, it is tasteful, well proportioned, made of quality materials – a pretty little jewelry box of a building.

While Yamasaki was in his time one of the most prominent architects of the 20th century, he was not one of the best. Perhaps his best building was the main terminal at what is now the Lambert-St Louis International Airport. His worst was also in St. Louis – Pruitt-Igoe, the notorious public housing project that was dynamited bit by bit beginning in 1972, being judged unfit for even poor people to live in. Most were merely banal. The best case I can make for his World Trade Center in Manhattan is that it offered easier targets than did the Empire State or Chrysler buildings a few blocks away, whose loss would have been an aesthetic as well as a human tragedy.

Yamasaki did not set the building on a barren plaza, as was the custom among designers of large commercial buildings of that day. He placed it instead amid a garden of sorts. As the plantings matured, it came to look like a turkey on a Thanksgiving platter decorated with parsley. On the ground, however, the mini-park is a much-appreciated amenity, although I remain mystified by the widespread local view that downtown Springfield has enough bustle that people need a place to escape it.

Except, arguably, for the Wright, none of these buildings is among the best by their firms. However, all are jewels compared to the major medical buildings, corporate headquarters, hotels and public office buildings erected since the 1970s. I suspect it is not architects but the ambitions of local clients that have cheapened. Which suggests another Trivial Pursuit question: “Name a major building since 1974 worth making the subject of a Trivial Pursuit question.”

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Editor’s note

Long

before he hit it big with “The Simpsons,” we knew Matt Groening as the

creator of “Life in Hell.” The angst-driven comic strip, described

variously as “funny,” “fatalistic” and “rude,” appeared in Illinois

Times for many years but has been gone for awhile. With this issue we

bring back Binky, Sheba, Akbar and Jeff to appear weekly with their

warped view of the world. See page 28 for the introductory strip, “Hell

for Beginners,” where you can get to know the characters, then each week

turn to the back of IT to find Hell among the classifieds. Even though

Groening, 57, of Portland, Ore., has become quite successful, he has had

to overcome obstacles to do so. “In grade school, Matt drew cartoons

when he should have been paying attention, which left strange gaps in

his education,” his publicist reports. “To this day, he does not know

his state capitals, and don’t bother asking him to multiply any numbers

between 7 and 13. He’ll just stare at you blankly.” –Fletcher Farrar,

editor