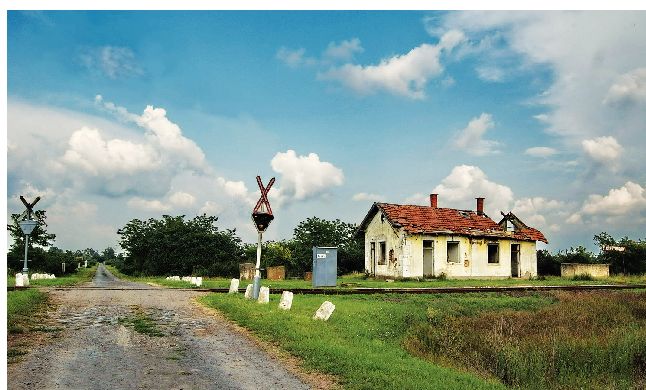

Devoid of life

Rural Illinois continues to bleed people

DYSPEPSIANA | James Krohe Jr.

Illinois has long been content to be a C-minus kind of state. That’s about the grade the 2010 census gave the state for its performance during the Oughts, when the number of people living in Illinois grew by only 3.3 percent while the nation as a whole increased its numbers by 9.7 percent.

The performance of many of the state’s remoter rural parts during that period earned it an F by any standard. A map published by the Institute of Government and Public Affairs at the University of Illinois depicts in a healthy green color the demographically robust 42 counties that gained population or held steady from 2000 to 2010. Shown in yellow – and making Illinois look like a nutrient-starved plant leaf – are the 60 Illinois counties (60!) that lost people in absolute terms. In its prestatehood days Illinois was compared by more than one visitor to Eden. If this keeps up, much of the Illinois countryside will soon have nearly as few people living in it.

Of course, rural Illinois has been hemor rhaging people since the 1860s or so. That’s when young people in particular started leaving for cities where they could find work and get laid by someone they didn’t meet at a family reunion. At the turn of the 20th century, Pike County had nearly 40 residents per square mile. When travel writer Bill Bryson dropped by in the late 1980s, he found Hull, Pittsfield, Barry and Oxville “devoid of life,” and no wonder. Population density was by then about 20 people per mile, or half what it was 80 years earlier.

By 2010 Pike’s density had slipped again, to 19 per mile. Sangamon County by comparison counted 226 people per square mile that year.

There are demographic smarty-pants in the form of rural counties with new state prisons crammed with lots of urban prisoners and counties within commuting distance of cities. Calhoun County, which shrank by 40 percent in the 1990s alone, even managed to gain five people in the 2000s, which makes me wonder whether an RV might have broke down about the time the census takers came by. Nonetheless, the general trend is clear. Whatever the value of its land as an economic resource, the value of rural Illinois as a place in the social sense is collapsing.

Heath care providers and school districts have been dealing with depopulation for years, usually via consolidation that compensates for fewer people per acre of service area by serving more acres. However, distance eventually imposes a limit to consolidation, a limit that already is being approached. Back in April, a plan to consolidate Virginia School District with the A-C Central School District – the latter itself a creature of consolidation – was voted down in part because people objected to how far their kids would have to be bused.

Dozens, maybe hundreds of isolated towns have long since passed the point at which their populations can sustain most forms of commerce. They would in one respect look familiar to Rebecca Burlend, who settled Pike County in the frontier era. Her new neighborhood, she wrote in her memoir, “is very thinly populated...and on that account it is not the situation for shopkeepers.”

Once the heart and lungs begin to fail, the head must eventually follow. What happens when the number of people that the Illinois countryside can economically sustain drops below the number needed to govern the institutions that modern towns need to sustain themselves? No town has more than a small percentage of citizens willing to devote themselves to the tedious business of running things. More and more school board races in Chicago suburbs for example are uncontested, and scores of Illinois communities had no candidates for dozens of open seats during the April 5 election, including towns in Sangamon and Christian counties. Indifference and lack of time are usually offered as reasons, but those can be overcome. What happens when the problem is not lack of interest but lack of bodies, especially those containing energetic younger people?

One doesn’t need a crystal ball to see the future that lies ahead for rural Illinois. All you need is enough gasoline to drive to eastern Kansas, the Dakotas and the drier flatter parts of their neighbor states. It’s a hard place to make a living in, and so many people have quit trying that bison threaten again to outnumber humans. It is hard to imagine the Illinois between the interstates becoming a Prairie State in fact as well as name, but the state already has hundreds of ghost towns whose residents never thought they would die either. Here is nostalgia with a vengeance, if the countryside really is going back to the way things were in the old days.

Contact James Krohe Jr. at [email protected].

Editor’s note

This

week’s cover story by Rachel Wells, “Gambling on the fairgrounds,”

presents a balanced and comprehensive report on the proposal to bring

year-round gambling to Springfield in the form of a “racino” with up to

900 slot machines. But here’s an opinion.

The

argument for expanding legalized gambling to generate revenue is that

we already have legalized gambling, so anyone who would become addicted

to it or damaged by it has probably already fallen into that hole. But a

national study of problem gambling says convenience makes a difference:

the number of problem gamblers within a 50-mile radius of a casino is

double that of those further away. UIUC economics professor Fred

Gottheil says a community encouraging casino development is the same as

encouraging a drug dealer to set up shop. Both “industries” create

economic activity, but both come with significant social costs. Gov. Pat

Quinn has said he has problems with the gambling bill approved by the

General Assembly, so it’s possible he could be persuaded to veto the

part of the bill allowing 900 slot machines to operate at the

fairgrounds. He’s probably waiting to hear whether there is any

opposition from Springfield’s religious or social services communities.

So far there has been little. Do you think this is a good idea? Or has

everybody been sleeping through the summer?–Fletcher Farrar, editor