TOWNS | Patrick Yeagle

Walking down the main business street in Cairo, Ill., it’s tempting to think that this spring’s floodwaters of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers were sent to put the languishing town out of its misery once and for all.

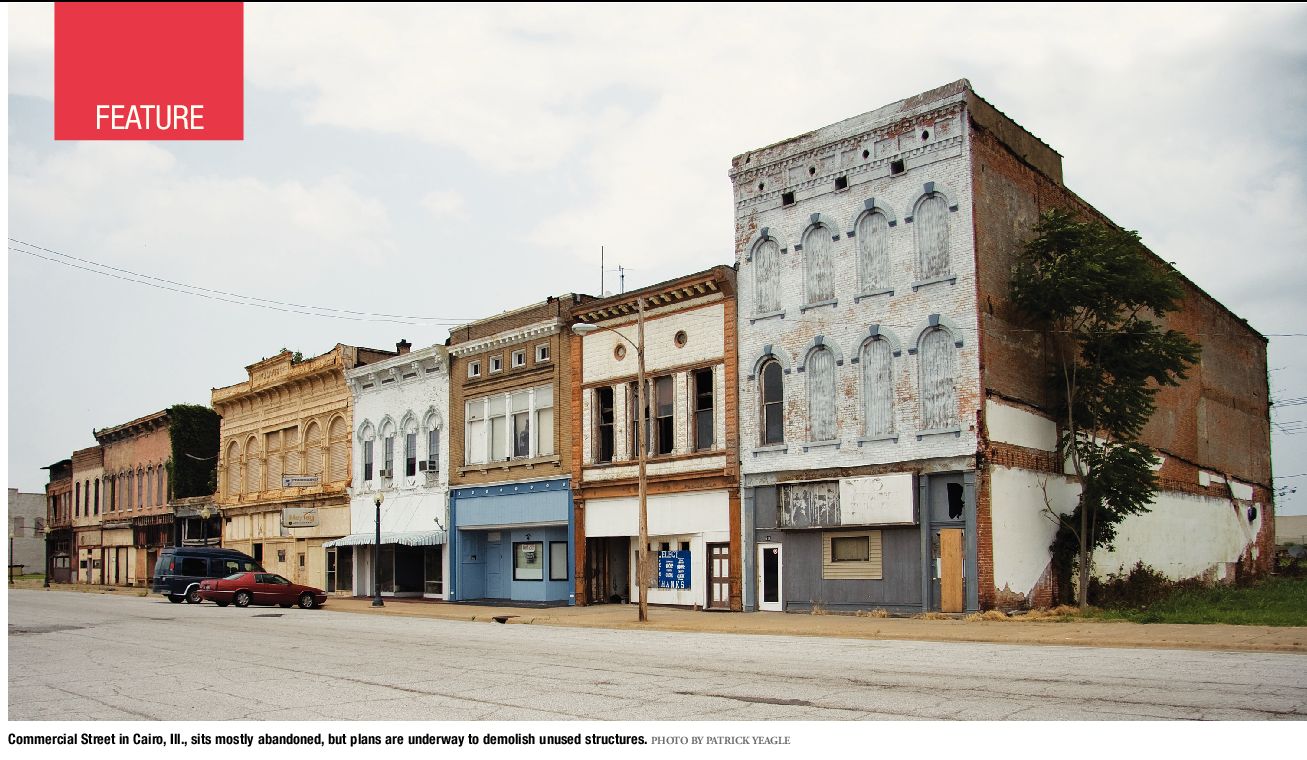

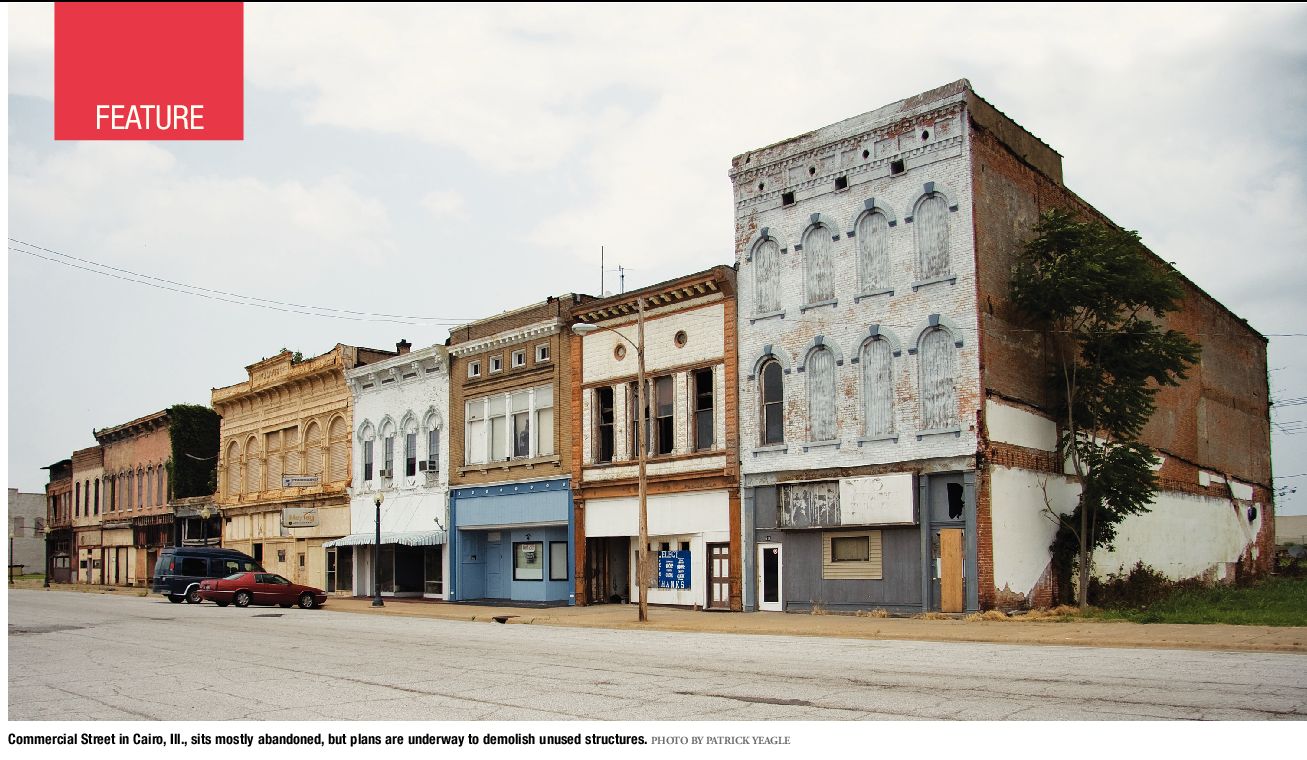

Many buildings along Commercial Street in Illinois’ southernmost town have long been abandoned, left to decay since businesses began departing decades ago. Brick facades crumble to the fractured sidewalks in untouched heaps, and rotting plywood that was meant to keep out trespassers now adds to the rubble, giving the desolate, quiet strip the feeling of a bombed-out war zone or a wild west ghost town. Only a handful of the old buildings are still in use on Commercial Street, among them a tavern and a retail store selling Maytag appliances, both stores flanked by the corpses of former businesses.

In late April and early May, Cairo and numerous other southern Illinois towns along the Ohio and Mississippi rivers faced rising floodwaters that threatened to wipe them off the map, leading Missouri House Speaker Steven Tilley to remark that he’d rather see Cairo underwater than see the Army Corps of Engineers blow up a levee that would flood Missouri farmland. Given that hypothetical choice by a reporter, Tilley remarked with a smile and not even a moment’s hesitation, “Cairo. I’ve been there; trust me. Cairo. Have you been to Cairo? You know what I’m saying, then.”

On the surface, Tilley’s flippancy toward the town’s future seems reasonable. What was once a bustling river city of 20,000 in 1915 is now an atrophied town of only 2,800, and the crumbling downtown, the near total lack of jobs and the prevalent poverty give the impression that the town is dying or already dead.

But a look beneath the surface reveals a different Cairo than the one often portrayed in gloomy stories of promise unfulfilled. Life goes on for the people of Cairo, despite the many projections of their town’s demise, and an enthusiastic new mayor is working to change the future of this historic place.

Older than Illinois itself The peninsula on which Cairo (pronounced care-oh) sits had been visited by Europeans as early as 1660, when the Catholic missionary Louis Hennepin explored the area as part of New France. In 1703, French pioneer Charles

Juchereau de St. Denys established a fort and tannery there, but it was raided by Native Americans and destroyed. Explorers Lewis and Clark even passed through the area in 1803 before officially starting their expedition to the Pacific Ocean in 1804.

It wasn’t until January 1818 that the city of Cairo was settled in earnest by John Comegys, an explorer and businessman from Baltimore who dreamed of building a great city at the confluence of the two rivers. The name “Cairo” allegedly comes from Comegys’ belief that the area resembled Cairo, Egypt, and southern Illinois has come to be known as “Little Egypt” as a result. Comegys died in 1820, and without his guidance the settlement languished until 1837, when businessman Darius Holbrook of Boston convinced the state legislature to incorporate the Cairo City and Canal Company.

The company built a shipyard, houses, a hotel, a store and the first of the town’s many levees.

Historians believe Cairo served as a waypoint on the Underground Railroad before the Civil War, and it became General Ulysses S. Grant’s headquarters for several months during the war. Though Cairo never saw action, thousands of Union troops trained there and fortified the strategic port, which became an important supply depot for Grant’s push into the Confederate south. Thousands of African Americans moved to Cairo during that time, with many more freed slaves moving there at the war’s end. Their presence would shape the city’s future for the next hundred years and beyond.

Cairo grew steadily as river commerce increased, and the federal government recognized its strategic location by building a combination customs house, federal court and post office there in 1872. At one point, the Cairo post office was the third busiest in the United States. Now known as the Cairo Customs House Museum, the building houses Civil War artifacts and numerous other historical items.

Residue of racism During the civil rights era of the late 1950s and early 1960s, Cairo’s African-American community watched the national struggle for equality with hopeful anticipation, but their own struggle was yet to come. Cairo’s longsimmering powder keg of discrimination and racial hatred exploded on July 15, 1967, when Robert Hunt, a 19-year-old African-American soldier home on leave, was arrested by local police on trumped up charges and later found hanged in his cell. His death was immediately deemed a suicide by the city’s white leadership, but African-American leaders protested to demand justice. What they got was a violent reprisal that precipitated three days of race riots. There had been other incidents of racially-motivated violence in the preceding decades, but Hunt’s apparent murder was a catalyst for change.