When Springfield went to the dogs

HISTORY | Tara McClellan McAndrew

In the middle 1800s, animal control in Springfield, like much of America, was an oxymoron. Cows, hogs and especially dogs roamed the streets and wreaked a variety of havoc, from destroying sidewalks and fences to hurting people. Unfortunately, those injuries could be fatal.

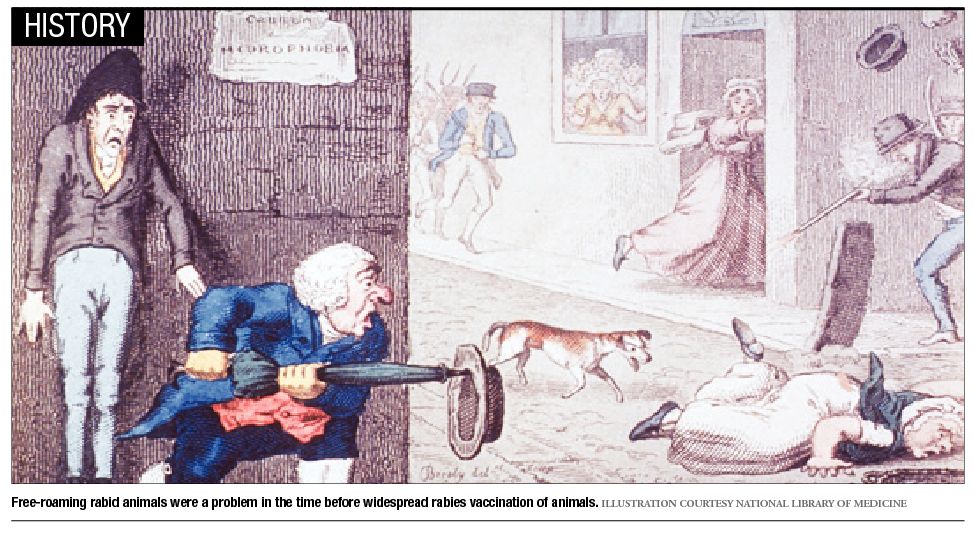

Rabid dogs weren’t uncommon then and, with no rabies vaccine for animals or humans at the time, a bite from a “mad” dog was often fatal and preceded by horrendous symptoms, including fever, sore throat, hallucinations, fear of water (hydrophobia), paralysis and coma, according to WebMD.com.

In an early attempt to control dogs, Springfield required dog owners to collar, tag and register their pets with the city. Still there were times when feral dogs would accumulate and spread the fear of “hydrophobia,” as rabies was commonly known then. At these times, city ordinances called for dog slaughters to prevent the spread of rabies.

Such a mass killing was held in 1860 on March 15 (appropriately, the Ides of March) and was heralded with an announcement in that day’s Illinois State Journal. “Slaughter of the Innocents” was the title. “The dog killing season commences today and it is quite likely that several worthless curs will be slaughtered before night. The city is bountifully supplied with dogs of all sizes and shapes, nine tenths of which are of no earthly use, and they are certainly far from ornamental, for the tails and ears of most of them have been closely subtracted, and the manner in which others of the tribe display their teeth to quiet pedestrians is more expressive than agreeable to women and children.”

It continued, “We like a good dog – one that has more sense than a cart horse and would regret to hear of the violent death of such a quadruped, but from all the information that we can gather on the subject, there are not many animals of that kind inside of the city limits. Let every owner of a good dog have him registered without delay by the marshal, for the dog law will be strictly enforced. The worthless curs need not be registered.”

It continued, “We like a good dog – one that has more sense than a cart horse and would regret to hear of the violent death of such a quadruped, but from all the information that we can gather on the subject, there are not many animals of that kind inside of the city limits. Let every owner of a good dog have him registered without delay by the marshal, for the dog law will be strictly enforced. The worthless curs need not be registered.”

The paper didn’t report how many dogs were killed, but whatever “worthless curs” escaped might have headed north because eight months later, Bloomington had a rabies scare. Its paper also supported a dog slaughter, according to a Dec. 5, 2010, Pantagraph article, which quoted the 1860 paper: “Better every one of (the dogs) should die than that one human being should suffer.”

There was no cure for rabies then, but there was a folk remedy called a “madstone.” According to the Winter, 1960 Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society, a madstone was a stone used to treat victims of “mad dog bites and snake bites.” The madstone was placed upon the bite and supposedly drew out the infection. “The stone would then be soaked in warm milk to remove the poison,” the Journal said. “The milk would acquire a greenish yellow scum, which was supposed to contain the poison, and the purified stone was ready for use again.”

The 2010 Pantagraph article said madstones were not stones, but “hard, roundish, porous-like concretions found in the stomachs of deer” and were precious commodities, often handed down through generations. It cited a 1900 Pantagraph article about a Bloomington family that said its madstone had been in the family for more than two centuries and originated in Wales.

Abraham Lincoln apparently had more than a passing belief in their curative powers. When his oldest son, Robert, was bitten by his own dog, Lincoln took him to Terre Haute, Ind., to receive a madstone treatment, according to Illinois Heritage magazine.

In 1885, French scientist Louis Pasteur developed a rabies vaccine for humans; he also developed one for canines. Sadly, the vaccines did not stop dog slaughters as a way to prevent rabies. India slaughtered dogs for this purpose until 1996, according to the Alliance for Rabies Control. And more recently, in early August, 2006, two provinces in China (Shandong and Guangdong) killed an estimated 50,000 dogs in response to an increase in human rabies deaths, according to CBS News and the Associated Press.

Contact Tara McClellan McAndrew at [email protected].