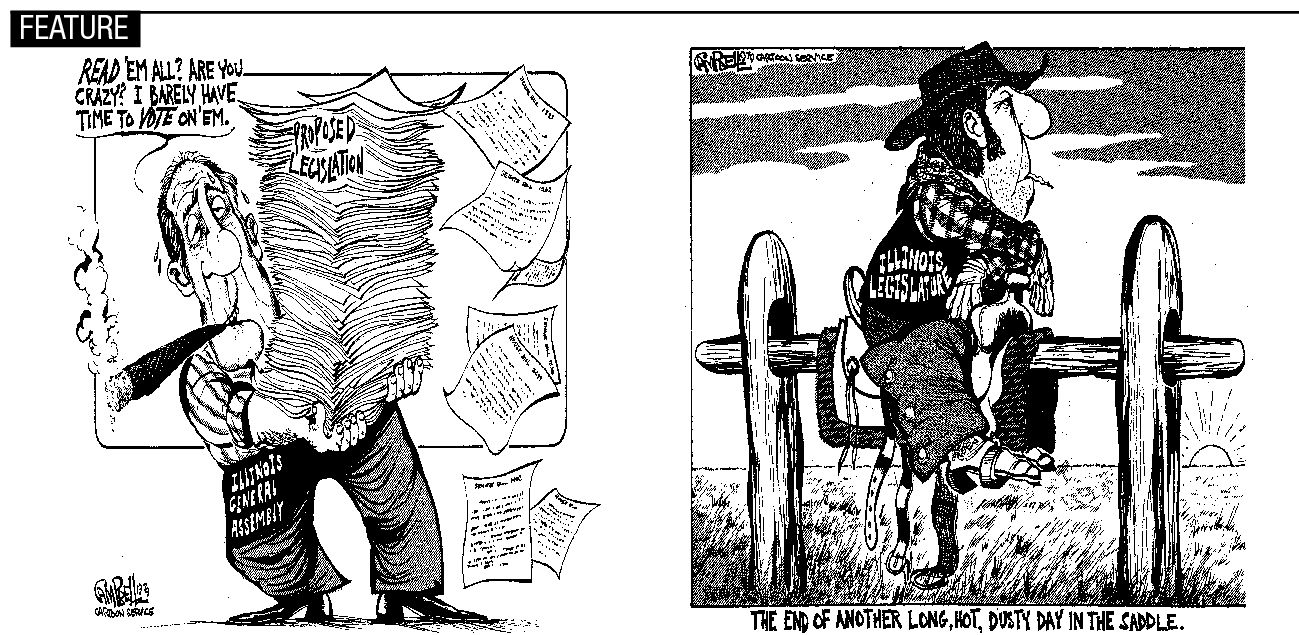

This picture of Illinois politics isn’t pretty

BOOK REVIEW | Robert E. Hartley

The title of this book, Illinois Politics: A Citizen’s Guide, is less than inviting when compared to many political items on bookstore shelves today. But the story between the covers tells a gripping tale of the state’s past and present, and will unnerve readers about prospects for the future.

the covers tells a gripping tale of the state’s past and present, and will unnerve readers about prospects for the future.

This is no treatise prepared just for lectures in a political science classroom. The target is everyone who lives in Illinois, sends children to schools, strives to succeed, elects officials, pays taxes and hopes for a better day. The story of Illinois politics as told by the authors is drop-dead fascinating, made so in part by a lively writing style and enlightening examples. Warning: The picture drawn is more than a bit depressing.

The book’s objective is to draw a concise picture of how Illinois is governed, and explain the political environment in which the results occur. Consequently, there is a large dose of how things are supposed work – the legislative, executive and judicial branches for example – enlivened by details of what reality looks like, and prospects for the future. Education is one highlight. While the state constitution requires a quality education for Illinois students, today’s outcomes fall short, and the authors tell us why. In brief, the inequities of funding are persistent and need changing. However, the word “reform” is not in the state’s political vocabulary.

Any student of Illinois politics knows the history of competition among geographic regions, namely Chicago, the collar counties and suburbs, and downstate counties. With popula tion shifts, pressures of diversification, and constant demands for attention, regional tensions remain at the heart of state politics. The authors explain how Chicago is still the Biggest Player in influence regardless of decreasing population numbers. They demonstrate that population growth, power and money have strengthened the clout of the suburbs. And, in devastating detail, the reader learns that the 95 counties making up downstate, containing just a third of the state population, are on the ropes politically, and are likely to remain there. After Chicago and the suburbs help themselves, downstate will get the leftovers – if there are any.

The authors – experienced in observing state politics – spend little time preaching solutions to readers. Nevertheless, the examples of failed reforms and trashed ideas they offer leave little to the imagination about prospects. This is most apparent in discussion of state finances and taxation. Given state spending habits and fear of higher taxes, the status quo appears most likely to prevail.

The description of the culture of corruption is disconcerting. The authors offer a number of useful examples, some well known, that demonstrate how corruption has plagued the state almost from its beginnings, and shows no decline. To make a point about the insidious nature of corruption, the book recounts the exposure of payoffs and case fixing in Cook County courts. The picture is nightmarish, and a caution for everyone.

Concluding the discussion of corruption, the authors state with sadness, “A key message of this chapter is that the scandalous and criminal behavior in Illinois politics and government is recurrent and systemic, and far too many citizens and public officials tolerate it.”

The current state of political control receives much attention, along with profiles of those who have accumulated power. First among equals is the mayor of Chicago, whomever holds the office. However, giving the mayor competition in bossism is Speaker of the House Michael Madigan, who holds the entire legislative process captive. In 40 years in the legislature and 30 years in House Democratic leadership, Madigan has created a stunning fiefdom of money and clout. His reach into the precincts of every county is at the heart of an intriguing discussion of the changing political scene, including the decline of political parties and the prevailing system of political contributions for which the sky is the limit. One can only gasp at the cost of current campaigns. Woven into this subject is the milk of state politics: lobbyists, special interests, political staffing, and patronage.

The authors’ conclusion: “Winning and control, in and of themselves, are the major goals of Illinois elections. Policy positions and outcomes are means to those ends rather than the ultimate goals of Illinois politics.” This and other statements affirm the conclusion that politicians are out to get what they can from the system, leaving the state with a “prevailing culture that focuses on the individual rather than the commonwealth.”

This book is a learning experience.

Robert E. Hartley, a former Illinois newspaper editor, is author of Paul Simon: The Political Journey of an Illinois Original and other books about Illinois history and politics. He currently lives in Colorado.